If a knee talks, who’s listening?

That’s the question facing orthopedic surgeons and rehab physicians as they learn to work with a new knee replacement that incorporates sensors and processors to send data about how the joint works from deep inside the patient’s body.

It’s one of a growing number of devices sending data to physicians to help them monitor their patients, including continuous glucose monitors and wearables to monitor for heart arrhythmia. With this influx of information, medtech companies are still ironing out how to make the data useful for doctors.

“This field is still very nascent,” said Jay Pandit, a cardiologist and the director of digital medicine for the Scripps Research Translational Institute in San Diego, noting that physicians simply haven’t got time to look at the raw data now flooding in from wearables — and soon from implantable devices.

Data still are far from being user-friendly, often requiring the physician to have a dedicated analyst reviewing the data on a third-party website, Pandit said. Most doctors have just seven to 10 minutes to meet with a patient, review their records and come up with a care plan, so there’s no time to analyze reams of raw data, he added.

Since the pandemic, the enthusiasm for remote patient monitoring devices has increased, but there aren’t any overarching guidelines on how to manage the data generated by these devices, Pandit said.

Still, that hasn’t curbed plans by smart-knee manufacturers.

“The talking knee is a reality,” Indiana-based Zimmer Biomet announced at the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons’ conference last year. The company was presenting its new knee-implant extension with an embedded sensor just days after receiving de novo clearance from the Food and Drug Administration.

Now, Zimmer, which developed the smart knee along with California-based Canary Medical, Inc., a company that creates sensors for medical devices, has begun selling the replacement joint, called Persona IQ. It can measure a patient’s range of motion, step count, stride length, and walking distance from inside the human body. Still, physicians don’t yet know how to use this data to help patients.

“Turning it from ‘I have data on a patient,’ to ‘I can make a diagnosis for a patient,’ or ‘I can tell a patient what they need to do differently,’ it’s going to take some time,” said Matthew Hepinstall, an associate professor of orthopedic surgery at New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine, and co-director of its Center for Computer Navigation and Robotics.

Eventually, sensors will detect problems with implants, help patients adjust their gait or provide data to predict patient outcomes. Meanwhile, competitors are creating systems that use wearable sensors to track patient recovery and hinting at their own plans for sensor-embedded implants.

Bill Hunter, Canary’s founder and chief executive, said in an interview that medical technology companies are already unleashing a wave of sensor-loaded devices in other sectors.

“Having this ability for the device to provide the clinician with actual feedback from inside the body has implications in most every major medical device,” he said. “So I do believe that you will see this showing up in all kinds of different ways.”

What can the data say?

Zimmer’s first challenge will be persuading physicians to use its Persona IQ device over traditional knee implants, Hepinstall said.

“I’m waiting for the wearable sensors to give enough data and for us to have enough experience with wearable sensors to understand how to act on that data before implanting something in one of my patients,” he said, adding that the sensor’s size means surgeons have to remove more bone when implanting a smart knee.

Still, said Hepinstall, “somebody’s got to put these devices in people for us to learn what they can do. Monitoring patients remotely in some way is a major priority.”

When new forms of data come in, it takes time to learn how to interpret and apply that information, Hepinstall added.

“Any time you get new information, types of information you didn’t get before, it’s not necessarily easy to figure out how to use that information effectively at first,” he said.

The data collected by these smart implants are similar to those tracked by wearable devices worn on the outside of the knee and connected to smartwatches. The main difference is in cost and compliance, physicians said, since about 30 percent of people stop using wearables, according to a 2016 survey by Gartner.

Taking data on a patient’s stride, gait and speed could help develop recovery curves to predict how patients will adapt to their implants, said Fred Cushner, Canary’s chief medical officer.

It also may be able to teach physicians how to reduce pain after a replacement and how best to position the replacement joint, he added. Cushner helped develop the sensors.

“You have to do studies, but everybody is inclined to believe that we'll be able to answer some of those unknown questions” once surgeons begin implanting smart knees and the data starts coming in, said Cushner, who is also an associate professor and orthopedic surgeon at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York.

He noted that the smart knee is only cleared by the FDA to track a patient’s activity and isn’t indicated to support clinical decision making.

Data coming from inside the patient’s body also may help scientists design better knees, said Peter Sculco, also an associate professor of orthopedic surgery at the Hospital for Special Surgery.

“That is an incredible treasure trove of research,” said Sculco, who consults for Zimmer but wasn’t involved in the development of the device.

What excites him about the smart knee?

“The ability to be able to compare and contrast the different ways we put our knee replacements in, their alignment, their balance, the designs that we use, the type of plastic we use, and then to somehow look at this gait-level data and say, ok, maybe this is a better way to do a knee replacement,” he said.

Zimmer confirmed it has additional studies planned of its Persona IQ device, though it didn’t share the specifics.

Starting with the knees

Commercial pressures are rising on joint-replacement manufacturers as the procedure shifts to ambulatory surgery centers and implants are increasingly viewed as a commodity.

“They have been an area where companies have faced incremental pricing pressure every year,” said Ryan Zimmerman, an analyst at institutional brokerage BTIG. “For companies that are looking to differentiate themselves, adding a smart implant component makes a lot of sense.”

Knees are Zimmer’s largest source of revenue and the company reported knee sales rose 8% in the first quarter of this year, and 11% in 2021 from a year earlier. In a May earnings call, the company declined to comment on whether Persona IQ would be material to the growth of its knee business this year or next.

“I won't talk about the number of hospitals that have been onboarded, but it is significant,” Zimmer COO Ivan Tornos told investors. “The patient pipeline is also significant, above our expectations.”

Knees, and the implants that go into them, are also a good place to start using sensors, added Canary Medical’s Cushner.

They offer scientists more “real estate” as Canary develops a smaller version of its sensor, he added. In Zimmer’s knee, the sensor is attached to the stem, which is drilled into the patient's tibia.

Knee revenue in 2021

| Company | 2021 knee revenue |

|---|---|

| Zimmer Biomet | $2.65 billion |

| Stryker | $1.85 billion |

| Johnson & Johnson | $1.33 billion |

| Smith & Nephew | $876 million |

SOURCE: Annual earnings reports

Cyborg revolution

The smart knee is part of a broader strategy by Zimmer to augment its products with its own robotics and technology, said Liane Teplitsky, the firm’s president of global robotics and technology and data solutions.

The sensors work much like pacemakers, she said.

“The information gets automatically downloaded to a base station that the patient has in their home, and [is] then uploaded to the cloud,” Teplitsky said.

Surgeons can use HoloLens smart glasses (made by Microsoft) to guide themselves through instrument assembly, and during surgery to implant the knee, Zimmer’s surgical robots assist and collect data.

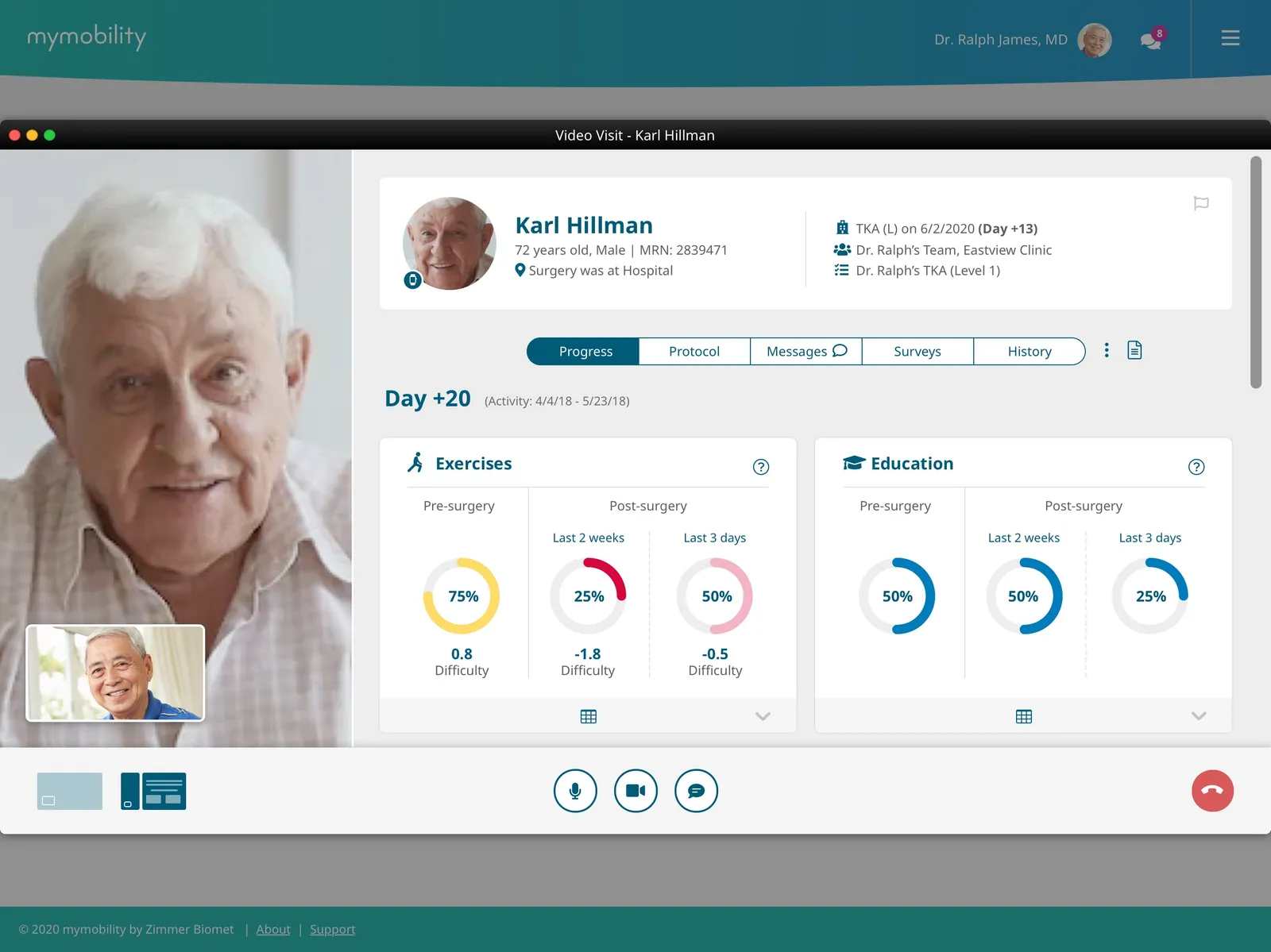

The smart knee connects to an iPhone application called Mymobility, which can pull in kinematic data from the implant and a patient’s Apple Watch to track exercise after surgery.

“Everything that we're thinking about now bringing to the marketplace will either generate data or collect data,” Teplitsky said. Eventually, Zimmer will be using sensors in more of its implants, including cementless knees and shoulders. Canary Medical already has patented sensors for heart valves, spinal implants and stent grafts.

Zimmer also has used data from the Mymobility app to power a feature called WalkAI intended to predict which patients may have a slower gait 90 days after hip or knee surgery. The company will need clearance from the FDA to use the data to make care recommendations.

“You can go from being able to predict to then being able to recommend,” Teplitsky said. “That's still the future. We can make no claims around that yet today, but that's ultimately the goal.”

Other companies look to sensors

Zimmer’s competitors have yet to introduce their own smart knee implants, but they are betting on the need for data, largely through wearables.

Stryker, the second largest maker of knee implants by revenue, last year acquired OrthoSensor, whose technology is incorporated in knee implants to help surgeons balance the knee during surgery. Zimmer and Smith & Nephew, the fourth-largest kneemaker, have used OrthoSensor’s technology in their knee-replacement systems.

Stryker also uses OrthoSensor’s wearable sensors, which are attached above and below a patient’s knee, to track their range of motion, gait and other information before and after a procedure.

“It's all about information that the surgeon is able to use for each and every unique patient that's out there. And its application is definitely for both pre-surgery to get some baseline type information for a shorter period of time, and then up to 90 days after surgery, so that you can really see progress,” said Don Payerle, Stryker’s president of joint replacement.

Stryker likely will begin adding sensors to implanted products as well, said Richard Newitter, an analyst with financial services firm Truist.

Johnson & Johnson also is working on smart implants, according to Shagun Singh, an analyst with RBC Capital Markets.

“They said they own over 50% share of the trauma market. And so they want to go to that market first,” Singh said.

Looking to the future

The technology may be nascent, but sensors that will allow patients and physicians to monitor their health and improve outcomes have become an “area of important focus and development” for the medical device industry, said Truist’s Newitter.

“It’s not just about the actual implant itself anymore — it’s about building an entire digital ecosystem around the care continuum for surgery,” Newitter said.

To be sure, sensors come at a cost. Zimmer prices its sensor-equipped implants at $1,000 more than those without sensors, notes RBC’s Singh.

It likely will be a few more years before there’s enough data to show the sensors can improve health outcomes and lower costs for insurers, according to Newitter.

“We’re interested to see if it takes off, similar to robotics,” said Zimmerman of BTIG. If it does, “you should see a lot of the other companies follow suit,” Zimmerman added.