Dive Brief:

- Women are underrepresented in studies of high-risk medical implants, according to a paper published in JAMA Internal Medicine Monday.

- The analysis of trials published from January 2016 to May 2022 found a median of 33% of study subjects were women. Women made up a significantly smaller portion of cardiovascular disease trials, accounting for 27% of the people enrolled in stent studies.

- Improved awareness and initiatives are essential to ensure adequate enrollment of women, wrote the authors of the paper.

Dive Insight:

Women differ from men in body size, hormonal variations and other ways that can affect the safety and efficacy of medical devices. However, women have historically been underrepresented in trials, creating gaps in understanding how devices will perform in many patients. The Food and Drug Administration published guidance to help address the problem in 2014.

The JAMA paper covers 195 studies that began before and after the FDA guidance. On average, 37% of participants in studies that began before 2010 were women. The figure fell to 32% in the 114 studies that began between 2010 and 2015. Women made up 34% of subjects in studies that started from 2016 to 2020. The researchers found no significant trend in the participation rate over time.

Around two-thirds of the trials studied cardiovascular diseases. Another one-fifth of the studies tested orthopedic products. Women made up a median of 29% of the participants in cardiovascular studies and 46% of the subjects in orthopedic trials. The combined figure for all other therapeutic areas was 47%.

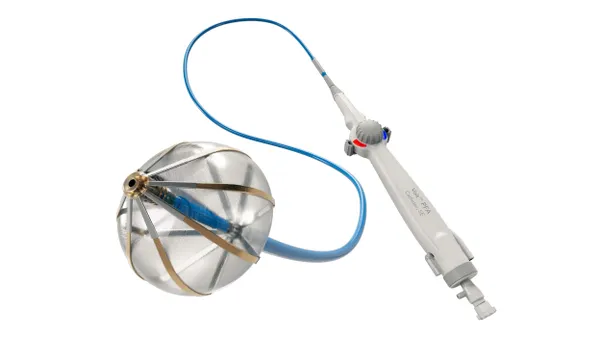

Stent studies drove the difference between the participation rates in cardiovascular diseases and other therapeutic areas. Seventy-three of the studies tested stents, making them the most common type of device in the analysis. Women accounted for 27% of participants in stent studies, compared to 44% of the subjects in valve trials.

The authors listed concerns about underdiagnosis or underreferral of women, perceived recruitment challenges and inclusion and exclusion criteria favoring men as potential obstacles to enrolling women. They also considered concerns fetal consequences as a potential barrier, but that explanation is refuted by the median age of over 50 years, the authors said, leading them to focus on other problems and solutions.

“The most limiting step for women’s recruitment is the screening stage; higher awareness of physicians may improve enrollment. Women-led studies are more likely to include women,” the authors said. “Stakeholders should consider implementing gender equity criteria for researchers involved.”