UPDATE: Feb. 19, 2019: The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) finalized its national coverage analysis regarding vagus nerve stimulation for treatment-resistant depression Friday, notably updating the clinical trial parameters to allow response, defined as an at least 50% improvement in depressive symptoms, as a primary outcome measure.

The move reflected consideration of feedback from the clinical community urging CMS to lower the bar from remission, which under the finalized decision memo will be considered a secondary measure.

The updated memo also responded to feedback not to exclude bipolar patients, with CMS adding a line saying, “If patients with bipolar disorder are included, the condition must be carefully characterized.”

LivaNova said in a press release it plans to submit a CMS-compliant clinical study design with the goal of beginning enrollment in the third quarter of 2019. The company aims to bring in 500 patients across at least 40 sites over an 18-month period.

Analysts at Jefferies called the changes to the decision memo the “best possible outcome” for LivaNova, while analysts at Needham & Co. estimated that every 500 patients enrolled could contribute $12.5 million in revenue for the company.

“We think that CMS changing their NCD is going to open the door to coverage by commercial payers, but it’s going to be a slow and steady process … we think it will gain momentum as we gain more clinical data,” LivaNova General Manager of Neuromodulation Edward Andrle told MedTech Dive.

Andrle said the company is looking to add to its VNS indications for epilepsy and treatment-resistant depression, with the next in the pipeline addressing generalized seizures, obstructive sleep apnea and heart failure.

Deep Dive:

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services could within days reopen a door closed a decade ago and begin to cover a surgically implanted neurostimulation device for a subset of severely depressed patients.

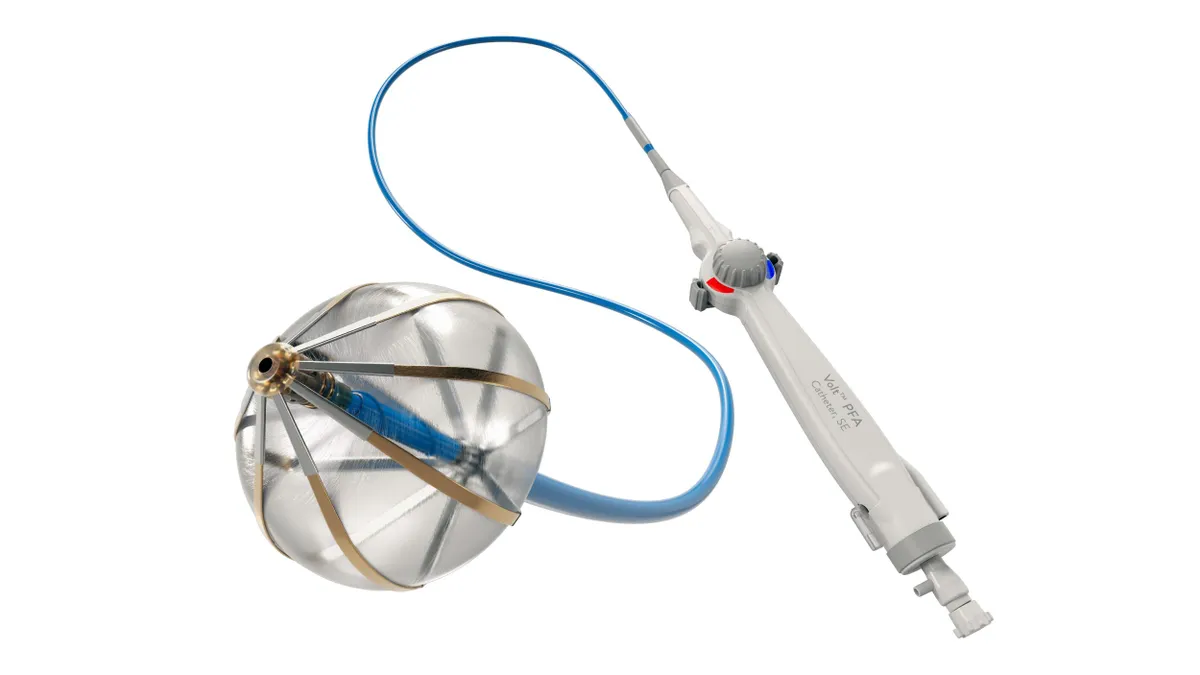

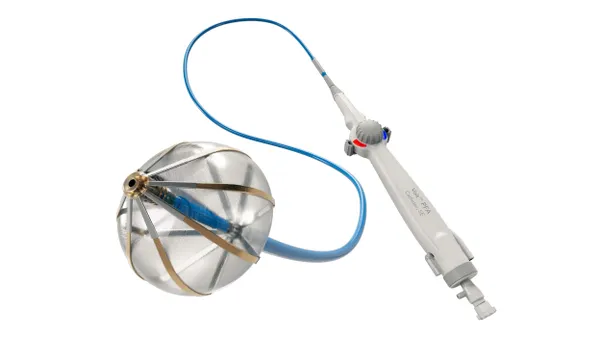

The government payer floated willingness to use its Coverage with Evidence Development track to support vagus nerve stimulation for treatment-resistant depression (TRD) in a Nov. 19 draft memo. The implanted, pacemaker-like device sends electrical pulses to the brain and won FDA approval for the TRD indication in 2005.

VNS is already covered by many insurers as an anti-seizure treatment for certain patients with drug-resistant epilepsy. Uptake has been slowed for TRD, though, since CMS denied coverage in 2007 for patients who had failed at least four depression treatments. A final agency decision is expected by Feb. 17.

Reconsideration of the pulse generator implant, programed via an external device, came from a late 2017 request from U.K.-based medtech manufacturer LivaNova, the only company with FDA marketing authorization that would immediately benefit from CMS widening access.

The agency sees more potential this time out but still is moving cautiously, calling the device "promising, but not convincing." It proposed covering agency-approved, double-blind, randomized and placebo-controlled trials with at least a one year follow-up to better inform whether to broaden access to the devices.

The coverage memo surprised some analysts, who had expected CMS would instead set up a registry.

Still, Needham & Co. estimated the randomized trials could include up to a few thousand patients, and that every 1,000 patients could add around $25 million in sales for LivaNova. Jefferies calculated that if coverage is extended more broadly, a TRD population within Medicare and Medicaid could encompass approximately 1.2 million patients. Considering a roughly $25,000 total cost per implant procedure, that could create a market worth $30 billion.

Based on trial parameters proposed by CMS in November, patients would be assessed primarily on timeliness and sustainability of remission, or full absence rather than partial reduction of symptoms.

Three dozen comments weighed in on the proposal. Some mental health advocates applauded CMS for taking another look at the device, while others took issue with the scope laid out for the proposed clinical trial.

Outspoken in both the CMS comment section and on a December conference call hosted by Jefferies was Scott Aaronson, director of clinical research at Baltimore's Sheppard Pratt psychiatric care system and principal investigator on LivaNova-funded study published in 2017 which tracked VNS effectiveness for TRD using a 795-patient registry across 61 sites over five years.

Aaronson raised concern that CMS' plans to measure total remission from symptoms after a year may not show the full potential of the therapy, noting the median time to response for patients in the registry he studied was one year, and median time to remission was at least four years.

But extending the study four or five years would make it extremely difficult to maintain blindedness, and Aaronson called subjecting severely depressed patients to sham treatment for that long "ethically questionable."

"When VNS is used for epilepsy is the goal remission from all seizures?" he wrote. "No, nor should it be with depression."

LivaNova built on Aaronson's recommendations, arguing that clinical response, defined as a 50% reduction in depressive symptoms, ought to be accepted as a primary endpoint.

Private payers are still not convinced. Insurer trade group America's Health Insurance Plans, whose members could face pressure to follow CMS' lead, discouraged coverage for TRD.

"This particular condition is very complex and this treatment relatively invasive and not without risks," an AHIP representative wrote in a separate statement to MedTech Dive. "While Vagus Nerve Stimulation may be appropriate in some cases, there is still limited evidence supporting its safety and effectiveness for widespread coverage."

Cowen Washington Research Group's Eric Assaraf said in a January note to clients he expects CMS will take into account feedback given during the comment period and "loosen certain criteria" in the final decision, including lifting the exclusion of bipolar or atypically depressed patients, which some commenters decried.

Needham analysts noted that with or without widened VNS sales, LivaNova's pipeline has other strengths, including a device for severe obstructive sleep apnea, a transcatheter mitral valve replacement product and a VNS device targeted to treat heart failure.

New entrants

Meanwhile, in a market long dominated by antidepressant drugs, access to device-based treatment options less invasive than VNS has expanded since the 2007 CMS decision.

Neuronetics introduced transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to the market with a De Novo clearance in 2008, a therapy involving a session in a clinician's office in which the patient wears a helmet-like device with a specially-formulated coil that stimulates a specific part of the brain, depending on the therapeutic indication.

TMS is approved for depressed patients who have failed between one and four treatments, and coverage for the treatment sessions has grown since competitor Brainsway entered the market in 2015, said Joseph Perekupka, the company's vice president of North American sales operations.

Perekupka said because TMS requires no surgical implant or at-home device purchase, costs associated with the TMS sessions can simply be billed as procedures, and reimbursement rates among states' Medicare and Medicaid programs as well as private insurers are now better than 90%.

"We're able to accomplish a lot of the same treatment parameters that deep brain stimulation devices propose to treat, and yet we're not invasive," he said, noting the company intends to seek expansion of its FDA-cleared indications from depression and OCD to include opioid use disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and post-stroke rehabilitation.

The company recently began a $30 million Nasdaq IPO effort, which Perekupka said was largely inspired by market growth and the success of its rival's IPO last year.

Makers of cranial electrotherapy stimulation (CES) products like Alpha-Stim, Electromedical Products International's wearable, at-home-use device that provides neurostimulation through electrodes that clip onto a user's earlobes, have historically had less traction with insurers. While the devices have traditionally been paid for out of pocket, the company's chief science and clinical officer Jeff Marksberry said his company is seeking a billing code for CES from CMS in 2019.

Marksberry said use of devices to treat conditions like depression has become progressively more accepted over the past two decades, due in part to more devices, more marketing and patient concern about side effects of standard depression drugs.

"[Patients] are trying to avoid that if they can," he said.

Also looking to boost reimbursement for its mental health technology is prescription digital therapeutics developer Pear Therapeutics.

Founded in 2013, Pear sells software-based cognitive behavioral therapy products, typically smart phone apps, meant to strengthen the longevity and quality of a patient's standard-of-care medication regimen. The company, a member of FDA's digital health Pre-Cert program, is currently marketing treatments for substance abuse and opioid use disorder, and its pipeline includes a product that targets insomnia and depression.

While Pear is still in the early stages of negotiating with insurers, Chief Medical Officer Yuri Maricich told MedTech Dive the company very much intends for its products to be viewed and treated like any other valuable therapy, particularly because helping patients complete their assigned treatment regimen can result in less expensive care in the long run.

"We see these as any other medication or any other therapeutic device where it's a prescription product and it's accessed and used as part of an overall treatment paradigm, including reimbursement," he said.