Dive Brief:

-

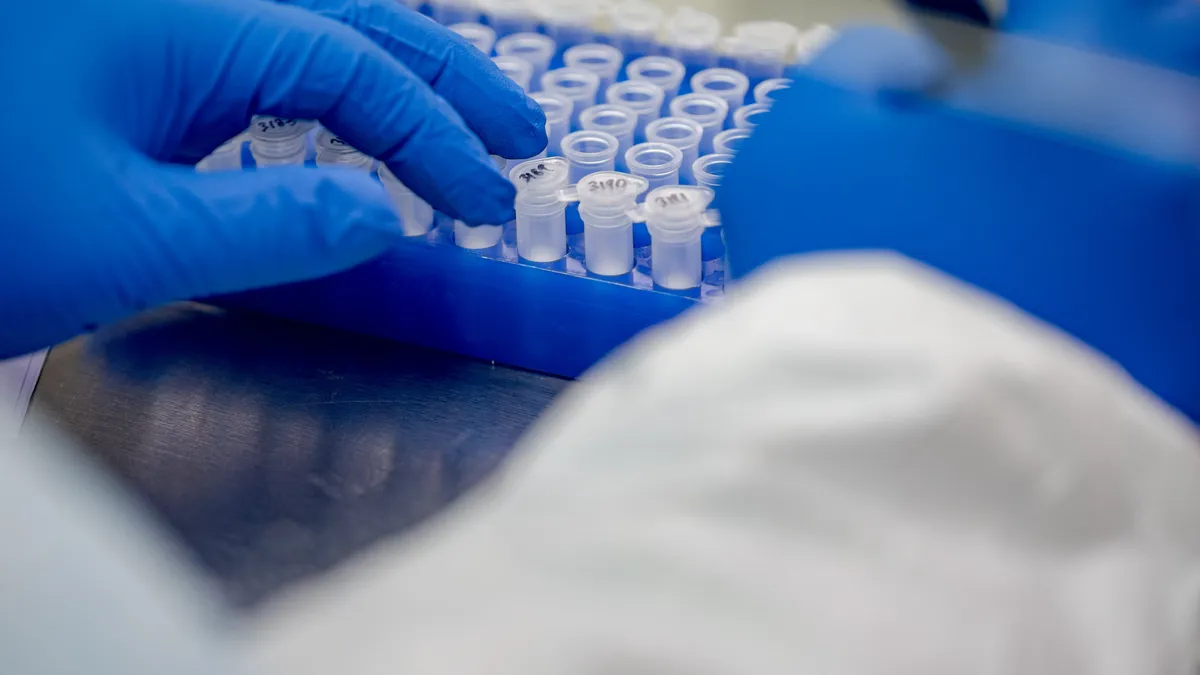

More than 70% of U.S. clinical laboratories have suffered significant delays to COVID-19 testing programs as a result of ongoing supply chain disruptions, findings from an Association for Molecular Pathology survey suggest.

-

The group said Thursday that many laboratories have validated three or more diagnostic methods to counter the risk that shortages of reagents or other materials will limit their ability to test samples. Tests from Abbott and Roche are many centers' first choices.

- AMP used the survey findings to argue that the U.S. government and commercial producers of reagents and other supplies need to give laboratories real-time updates on the availability of testing materials.

Dive Insight:

The simultaneous scaling up of testing capacity at laboratories around the world in response to the coronavirus pandemic has put pressures on supply chains that handle reagents and other materials used to show if a patient is infected.

Between April 23 and May 5, AMP polled representatives of 118 U.S. academic medical centers, commercial reference laboratories and community hospitals to understand how those pressures have impacted testing centers. The poll showed that supply chain disruptions are a widespread, ongoing problem constraining U.S. testing capacity.

According to the survey, access to swabs is currently the most common problem, with 60% of those polled saying availability is limited. A further 31% of respondents previously struggled to obtain swabs. The other main access issue involves testing media, which 53% of respondents said is in short supply. AMP identified seven groups of products that 19% or more centers are struggling to source.

Laboratories of all types are finding it similarly hard to source most types of materials, according to the survey. The exception is testing kits, which are in short supply at 13% of commercial laboratories and 40% of academic medical center and community laboratories.

Despite the persistence of widespread shortages, there are signs that supply chains are adapting to increased demand. About one third of respondents are still contending with limited availability of testing kits and reagents, but even more laboratories have come through shortages of those materials and now have ready access.

However, the active and resolved supply chain disruptions have halted testing. One in five laboratories surveyed said supply chain interruptions have stopped them from testing for the virus altogether. Many more laboratories have delayed or decreased testing in response to supply chain problems.

Faced with unreliable supply chains, many laboratories, particularly those in academic and hospital settings, have validated three or more testing methods to provide them with more options. The availability of reagents and supplies is dictating which of the methods the laboratories use to process the samples.

Products to detect SARS-CoV-2 sold by Abbott and Roche are the first choice assays in 16% and 17% of centers, respectively, making them the most popular tests after in-house diagnostics with emergency use authorization. Cepheid’s Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2 is also widely used, with more than half of respondents deploying it as either their primary, secondary or tertiary testing method.

Most laboratories plan to add additional tests to increase their overall capacity. If the respondents hit their targets, 42% of commercial laboratories will have the capacity to process more than 2,000 tests a day, up from 14% at the time of the survey. Other groups have similarly ambitious targets, with 79% of academic medical centers aiming to handle 500 or more tests a day. Less than 20% of centers were at that level at the time of the survey.

AMP wants other groups to help support the scaling up of capacity. Requests made by the trade group include a call for greater transparency about the availability of testing materials and a push for the reprioritization of supplies based on clinical testing needs. The AMP requests come more than a month after public health groups urged President Donald Trump to act to ensure the availability of reagents and other testing materials.

However, the Trump administration has instead deferred to states, putting the onus on them to establish "robust" testing programs while forcing many governors and local officials to compete against each other and the federal government for scarce test supplies.