Dive Brief:

-

Use of a self-applied, wearable electrocardiogram (ECG) patch improved the diagnosis of atrial fibrillation (AF) in a Janssen Pharmaceuticals-funded clinical trial.

-

Almost 4% of the 1,366 participants who wore the patch were diagnosed with AF in the first four months of the study, as compared to 0.9% in the similarly-sized control arm.

-

The finding suggests the patch improves detection of AF, but the current lack of long-term outcomes data means it is unclear whether this translates into reduced risk of stroke.

Dive Insight:

The CDC estimates 2.7 million to 6.1 million Americans have AF, making it the most common form of heart arrhythmia. These patients have a five-fold greater risk of stroke, a life-threatening condition that occurs when blood supply to the brain is blocked. AF is thought to cause one-third of strokes.

Despite the strong link between AF and the fifth leading cause of death in the U.S., heart arrhythmia goes undetected in many people. Around one-fifth of people who suffer AF-related strokes were not diagnosed with heart arrhythmia at the time of their stroke. If doctors could diagnose AF in these patients sooner, they may be able to intervene with anticoagulants to prevent strokes and thereby avoid many deaths and disabilities.

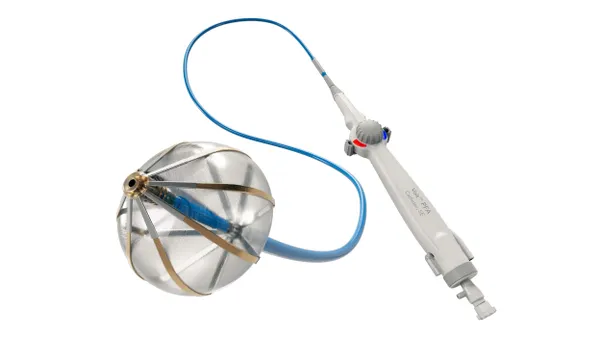

Today, cases of AF are typically diagnosed when physicians check their patients for pulse palpitations or perform ECGs during routine assessments. However, the statistics on undiagnosed AF shows this approach is missing a significant minority of cases of the arrhythmia. Digital health companies, such as AliveCor, argue monitoring people using smartphones, smartwatches and patches will improve the diagnosis of AF.

To test the idea, researchers at Scripps Translational Science Institute contacted members of Aetna health plans who were not diagnosed with AF but were at risk of the arrhythmia based on their age and comorbidities. People eligible to participate in the virtual, siteless clinical trial were randomized to either wear an ECG patch or receive routine care.

After four months, an analysis of claims data linked the patch to a 3.1% control-adjusted increase in the rate of AF diagnosis. The improvement was big enough for the trial to meet its primary endpoint. Participants in the patch group were also more likely to start anticoagulant or antiarrhythmic therapy, or undergo ablation.

The big, unanswered question is whether increases in diagnoses and interventions translate into improved health outcomes. Today, the link between diagnoses and outcomes in AF is unproven and disputed. Writing in 2016, physicians Adam Cifu and Vinay Prasad warned that “screening for atrial fibrillation may be beneficial but there is also a reasonable likelihood that its harms will outweigh its benefits.”

A follow-up to the Scripps ECG patch study may allay these concerns. The researchers plan to assess the clinical outcomes of patch wearers after three years. That analysis may show whether the treatment received by people with asymptomatic, patch-detected AF reduces the risk of stroke.