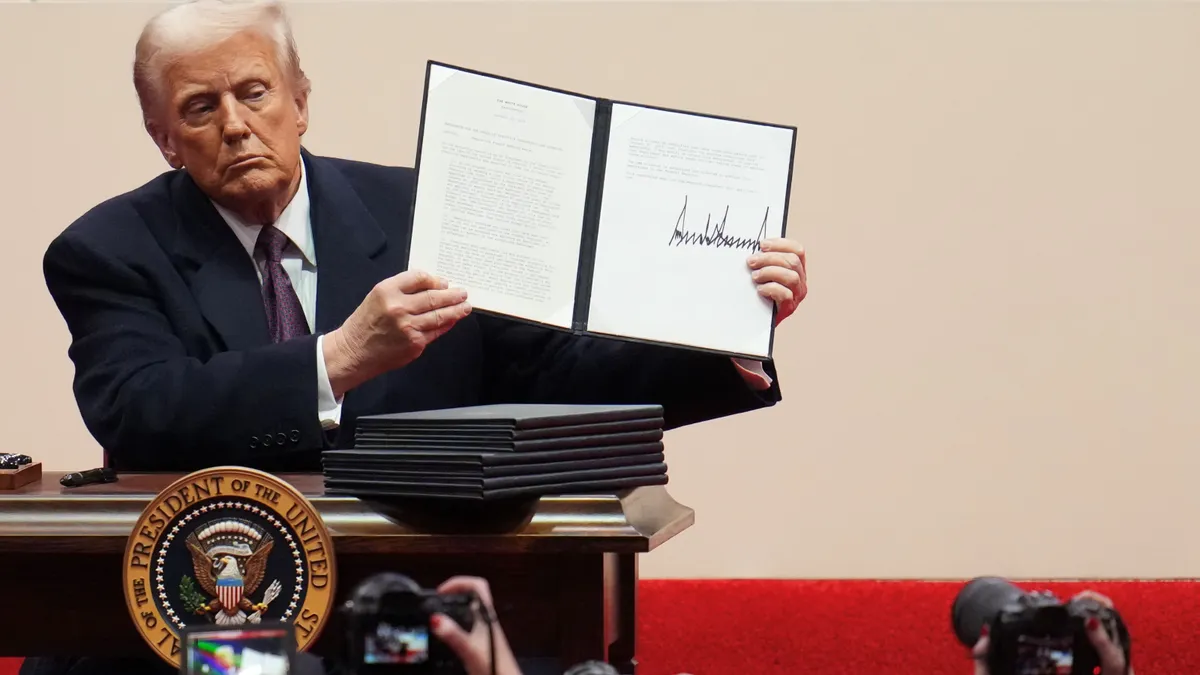

The Trump administration is proposing sweeping changes to the decades-old rule regulating the privacy of Americans' sensitive medical information in a bid to remove barriers to value-based care, give patients more agency over their data and nix regulatory overhead.

The roughly 360-page rule proposed Thursday is varied and complex, but seems to be responsive to industry concerns. If finalized, it would loosen a number of long-held standards for the privacy of protected health information under the HIPAA privacy law passed in 1996.

As a result, it would be easier for providers to share data and contact trace for the novel coronavirus as cases surge in the U.S. COVID-19 deaths and hospitalizations both reached record highs on Wednesday, sparking renewed worries about virus containment as the country nears approval of a vaccine.

The Trump administration has issued a flurry of regulations in recent weeks in a last-ditch effort to solidify its healthcare agenda before the January inauguration of President-elect Joe Biden.

Officials said there's nothing explicitly partisan in HHS' sweeping proposed rule, though it's still being digested and — given HIPAA's expansive scope — could have unforeseen consequences down the line.

It's still unclear how the private sector and Biden's incoming administration will react as they navigate a tricky health privacy landscape further complicated by the pandemic. A new HHS could seek a pause or an extension on the 60-day comment period, though the broad rule overall doesn't seem to include any partisan snags.

"I don't see these as hot button issues from a political point of view. So we'll see," HHS Deputy Secretary Eric Hargan told reporters Thursday.

And, though any big regulatory change creates complications, on the whole, the rule lines up with other Trump administration rules on issues like interoperability and fraud prevention.

More flexible data sharing during crises

The proposal applies to health information maintained or transmitted by HIPAA-covered entities, including providers, health plans and clearinghouses. One goal in revamping the privacy regulations was to make information sharing more efficient, especially during health crises like the opioid epidemic and the coronavirus outbreak, according to top health officials.

If finalized, it would loosen rules about disclosing information during emergencies, facilitating greater coordination among health companies and family and caregiver involvement.

Currently, covered entities can only disclose personal health information to avert a threat to patient safety if the threat is "serious and imminent."

The rule would modify that threshold to when a harm is "serious and reasonably foreseeable," as it's not always possible to know when a viable threat or health need will come to a head, HHS Office of Civil Rights Director Roger Severino told reporters.

It's a looser standard, according to Matt Fisher, healthcare attorney at law firm Mirick O'Connell, but makes sense given the number of health crises the U.S. has faced in recent years. The change would allow covered entities to more smoothly share data during emergencies without waiting for HHS to issue a waiver.

The move could help with contact tracing efforts. For example, if an emergency room doctor treats an elderly patient with COVID-19, the physician could contact the patient's nursing home to flag the threat, without having to worry about violating the privacy law.

The proposed rule also loosens HIPAA restrictions on when covered entities can disclose a patient's personal health information to their families and caregivers during a healthcare emergency.

The threshold used to be based on a provider's professional judgment, but HHS is proposing relying instead on an organization's good faith belief disclosing data will help a patient, based on things like a patient's advance directive or knowledge of their relationship with a close family member.

For example, if a young adult patient overdoses on opioids, their physician can inform their parents. However, the proposed rule doesn't preempt stricter privacy rules, called 42 CFR Part 2, meant to provide additional protection for the records of patients with substance use disorder, officials specified.

Relying on the legal concept of good faith is a lower burden of proof than professional judgement, giving OCR more wiggle room to question something retrospectively, lawyers say.

That makes it a bit easier for regulators to say something happened in bad faith, rather than due to bad professional judgement. This distinction could be important for provider culpability if and when a patient complains, Fisher said.

Boosting value-based care

Normally under HIPAA, entities have to limit the disclosure of personal health data to the minimum necessary for patient care.

However, the proposed rule creates an exception: Plans and providers could use health data much more broadly if it's for care coordination and case management of a person.

The relaxation is tailored to a degree — it only applies to care coordination and case management activities at an individual level, so payers and providers can't apply it to information for an entire population. However, it would facilitate broader requests at the individual level, allowing different organizations participating in the care of a single patient to get a fuller picture of their health.

For example, if a patient joins a program meant to help them stop smoking, the health insurer managing the program can get their entire record from their provider, not just data about their smoking history.

The rule would also allow entities to disclose data to social services agencies, community-based organizations and other health-related parties for individual-level care management.

It's a net positive for care coordination, experts say, though there could be unintended consequences, such as oversharing or privacy breaches due to wide data dissemination. "It's going to take time to figure that out, in parsing through the exact language of the changes," Fisher said.

The proposal aligns with other recent regulatory changes from the Trump administration aimed at fostering value-based arrangements, including finalizing rules rolling back provisions of the Stark Law and Anti-Kickback Statute in late November.

Eye on interoperability

The proposed rule also conspicuously interweaves with the Trump administration's push to foster interoperability, clearing up key questions about how two sweeping information blocking rules finalized by HHS in March will harmonize with HIPAA stipulations.

Like the interoperability regulations, the HIPAA proposed rule requires entities to give patients access to their own medical data, but clarifies the format entities should share data in, how much time they have to share it and when fees can be charged for access.

HHS is proposing shortening the window healthcare organizations have to respond to patient requests for data, or a request to send it to another provider or third party, to 15 days, with a potential 15-day extension.

Currently, covered entities have 30 days with a potential 30-day extension.

Companies would have to respond to records requests from other health organizations for electronic health information sent through standardized application programming interfaces, as dictated in the interoperability rules.

The rule would also allow patients to collect their data in person. For example, a patient seeing their own X-ray could take a photo on their smartphone and email it to their family.

It also clarifies when health data needs to be given to a patient for free. The transaction must be free if the patient gets it in person, if they use an internet-based method like a patient portal with a view, download and transmit functionality to get it electronically or if they get it on a personal health application connected via API.

However, payers and providers are allowed to charge patients a "reasonable, cost-based" fee if any supplies or labor went into copying the health data into electronic or paper form, postage and shipping or summarizing the data.

If they do charge for data, they must post the pricing and give patients a specific estimate upon request, along with an itemized bill afterward.

The proposals are intimately connected with the interoperability regulations, Hargan said, in a bid to smooth out complications down the line if the information sharing deadlines had kicked in with the old HIPAA still in effect.

HHS has twice delayed compliance deadlines for the interoperability rules to free up provider resources during COVID-19. Now, providers and vendors must be able to share medical data via standardized APIs by April.

The proposed rule, which has not yet been published in the Federal Register, would also nix the HIPAA requirement that providers get a patient's written acknowledgement they've read the notice of privacy practices, a requirement Severino called a "tremendous waste of time and effort."

Overall, HHS estimates the wide-ranging proposal would save $3.2 billion over five years.