Dive Brief:

- Researchers have linked cochlear implants to new bone formation and long-term residual hearing loss in a study of 123 patients published Tuesday in the journal Radiology.

- Ultra-high spatial resolution CT detected new bone formation in two-thirds of the patients within four years of implantation. Those people suffered more long-term residual hearing loss than their counterparts without new bone formation.

- As well as potentially affecting hearing, new bone formation could complicate device fitting. future use of gene therapy to restore cochlear function and re-implantation surgery.

Dive Insight:

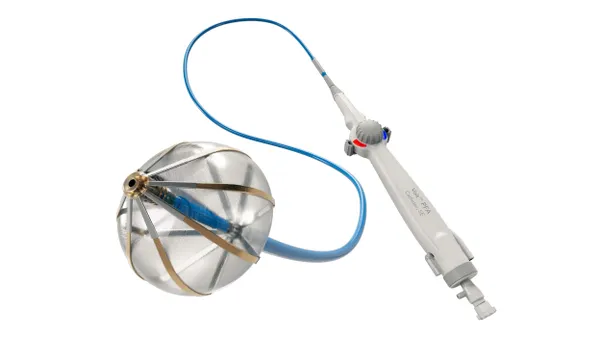

Cochlear implants consist of an external device that sits behind the ear and a component that is put under the skin. That implanted component stimulates nerves in the cochlea, part of the inner ear, to send sound to the brain. While the implants cannot restore normal hearing, they can help people with severe-to-profound hearing loss to understand speech.

Animal studies and post-mortems have linked the implants to new bone formation, potentially as a result of an inflammatory response and resulting fibrosis. However, physicians previously lacked the means to detect new bone formation in living patients.

A team in the Netherlands identified an ultra-high spatial resolution CT scanner as the tool that could shed light on whether cochlear implants are associated with new bone formation. Using the scanner, the researchers detected new bone formation on 83 of the 123 patients in the study.

The bone formation may have implications for hearing. Long-term residual hearing loss in patients with new bone formation was 22.9 decibels, compared to 8.6 decibels in their peers without new bone formation. Long-term hearing preservation compared to the first fitting was 48% in the new bone formation patients and 78.6% in other subjects, although the difference fell short of statistical significance.

Those figures are based on an analysis of just 24 of the patients. The researchers excluded patients with a pure tone average over three frequencies higher than 90 decibels at the first fitting because "they were not considered to have functional residual acoustic hearing."

More work is needed to understand the therapeutic consequences of new bone formation. Co-lead author Floris Heutink sees the imaging technique used in the study serving as a tool for gathering more information on the "occurrence, time course and the pathophysiology" of new bone formation in recipients of cochlear implants.

Kevin Brown, associate professor at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine and treasurer of the American Cochlear Implant Alliance, noted in an emailed statement that the study evaluated patients for hearing in the mid to high frequency range who had on average severe or worse hearing.

"That is why their cohort started with such poor hearing to begin with," Brown wrote. "What is more interesting in the cochlear implant field is that we are able to, with very high fidelity (90% to 95% of time), preserve the low frequency information in such a way that the patient receives mid and high frequency information from the implant (mid-range and treble) and low frequency (bass) information acoustically. These patients do amazingly well and it is a really exciting option for patients that otherwise do not have a great option to help with their hearing loss."

The release of the paper coincided with news of a change in leadership at Cochlear North America, a manufacturer of the implants. As of April 1, 2022, Tony Manna will retire as president, Cochlear North America and be replaced by Lisa Aubert, who joined the company in 1994 and currently serves as VP of sales for North America.

Note: This story has been updated with comments from Kevin Brown, associate professor at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine and treasurer of the American Cochlear Implant Alliance.