Dive Brief:

- Scientists at the University of California-Davis say they have taken the first 3D pictures of the whole human body using a medical imaging scanner that combines positron emission tomography (PET) and X-ray computed tomography (CT).

- The technology produces "movies" that can track drugs as they move through the body and is expected to have applications ranging from improving diagnostics to tracking disease progression.

- The scanner was built by Shanghai-based United Imaging Healthcare (UIH), which plans to manufacture the devices for the healthcare market. The developers expect to show the first images of humans taken with the new device at the upcoming meeting of the Radiological Society of North America, which begins Nov. 24 in Chicago.

Dive Insight:

UC Davis scientists Simon Cherry and Ramsey Badawi came up with the idea for the total body scanner 13 years ago. In 2011, they received a $1.5 million grant from the National Cancer Institute that allowed them to begin laying the groundwork for the project with other collaborators. In 2015, a $15.5 million grant from the National Institutes of Health provided a big boost toward getting the scanner built.

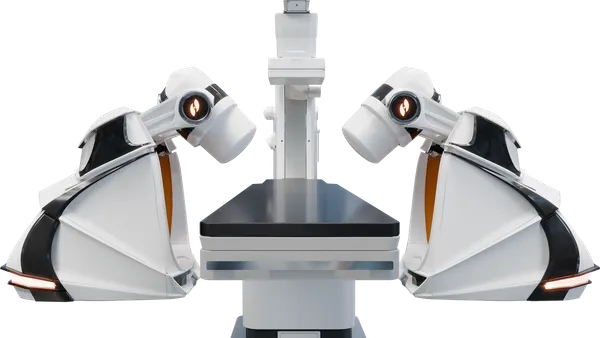

Called EXPLORER, the machine captures radiation more efficiently than other scanners and can therefore produce an image in as little as one second, enabling movies to be constructed from the images, according to the UC-Davis scientists. The first images were acquired in collaboration with UIH and the Department of Nuclear Medicine at the Zhongshan Hospital in Shanghai.

The device produces higher-quality diagnostic scans and can operate with a radiation dose up to 40 times less than current PET scans, making it feasible to conduct repeated studies in an individual or reduce the dose in pediatric studies, according to the researchers. All the organs and tissues of the body can be evaluated simultaneously.

"The tradeoff between image quality, acquisition time and injected radiation dose will vary for different applications, but in all cases, we can scan better, faster or with less radiation dose, or some combination of these," Cherry, who is distinguished professor in the UC Davis Department of Biomedical Engineering, said in a press release.

UC Davis is working with UIH to get the first system delivered and installed at the EXPLORER Imaging Center in Sacramento, California, and the scientists hope to begin research projects using the machine as early as June 2019. The Davis team also is working with Hongcheng Shi, director of Nuclear Medicine at Zhongshan Hospital in Shanghai, to expand the scope of early human studies on the scanner.

"While I had imagined what the images would look like for years, nothing prepared me for the incredible detail we could see on that first scan," Cherry said. "While there is still a lot of careful analysis to do, I think we already know that EXPLORER is delivering roughly what we had promised."