The Food and Drug Administration on Friday authorized for emergency use a coronavirus vaccine developed by Moderna and U.S. government scientists, clearing a second shot that can protect against COVID-19 as the pandemic's impact reaches grim new heights.

The FDA authorization, which limits use of the vaccine to adults 18 or over, sets in motion federal and state plans to deliver millions of doses across the country in the coming days and weeks. The agency's decision was delivered one day after a strong endorsement of Moderna's vaccine by a panel of independent experts, and a week after the regulator cleared a similar shot from Pfizer and BioNTech.

Emergency use authorizations like those granted to Pfizer and Moderna are special kinds of approvals granted by the FDA during public health emergencies.

"We're now the first country that has authorized two COVID-19 vaccines that demonstrate clear and compelling efficacy," said Peter Marks, head of the FDA division that reviews vaccines, in a conference call Friday night.

Both vaccines are historic scientific achievements, arriving less than a year after researchers sequenced the genome of a new virus spreading through China. And both are sorely needed, with more than 2,500 U.S. residents dying each day and record numbers of people hospitalized nationwide.

Supplies of each will be extremely limited for months, however: Moderna and Pfizer expect to produce about 40 million doses for distribution throughout the country by the end of the year, enough to vaccinate 20 million people.

Moderna supported its request for emergency authorization with results from a clinical trial that began in July and enrolled just over 30,000 volunteers. Data released in November showed the shot was 94.1% effective at preventing COVID-19. At the pre-specified point when Moderna measured efficacy, one hundred and eighty-five participants who received placebo were confirmed to have the disease, versus only 11 who got Moderna's vaccine.

Importantly, no one vaccinated with Moderna's shot developed severe COVID-19, compared to 30 who had got placebo.

Whether Moderna's shot can prevent asymptomatic infections or transmission of the virus is still unclear, although data made public this week suggested such protection may be possible. Researchers are also unsure how long immunity lasts.

Side effects to Moderna's vaccine, mostly flu-like symptoms such as chills, fever, pain and fatigue, are typically mild to moderate in nature, and more frequent after the second injection. In a small percentage of people in Moderna's study, they were more severe.

While Moderna's trial was large, authorization means millions of people will soon receive the company's shot and rarer adverse reactions could be observed. Regulators, for instance, are monitoring for allergic reactions after four such cases were seen in healthcare workers given Pfizer and BioNTech's vaccine this past week.

On the FDA conference call, Marks speculated one ingredient in Pfizer's vaccine, polyethylene glycol, "could be the culprit" and added that the agency will be closely watching the rollout of Moderna's vaccine, which also contains the same ingredient.

Still, "we just don't know at this point," Marks emphasized. "We'll just have to use our good pharmacovigilance to monitor what's going on."

Doran Fink, the deputy director of the agency's vaccine division, said Thursday the agency is working with Pfizer to better highlight the need for monitoring after vaccination. He added, though, that the detection of those four cases is evidence safety surveillance systems are "working exactly as designed."

Moderna hasn't reported any vaccine-related anaphylaxis in its study. Company officials at Thursday's meeting said they've seen just one allergic reaction, in a woman with a soy allergy, among the roughly 1,700 trial participants tested with one of the eight other vaccines Moderna has tested in people.

Still, the FDA is taking precautions. The agency is advising medical personnel not to give the Moderna's coronavirus vaccine to people with a known history of severe allergic reactions to any component of the shot, and to have treatment on hand to deal with any that still might occur.

Three cases of Bell's palsy, a temporary type of facial paralysis, were observed among study participants given Moderna's vaccine, versus one among those who received placebo. That concerned some committee members, since Pfizer and BioNTech reported four cases in vaccinated volunteers in its study. FDA reviewers haven't confirmed a link between the events and vaccination, however, indicating the rates are similar to what would be expected in the general population.

Although Moderna and Pfizer both worked furiously to scale up manufacturing this year, production won't ramp up significantly until 2021, when both developers expect to produce hundreds of millions of doses or more. The scarcity of supplies makes the success of other vaccines, such as candidates from Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca, critically important. Results from J&J should arrive first, likely by the end of January.

In the meantime, the limited doses available will be administered first to high-risk groups before the broader population, which may have to wait until between April and June of next year.

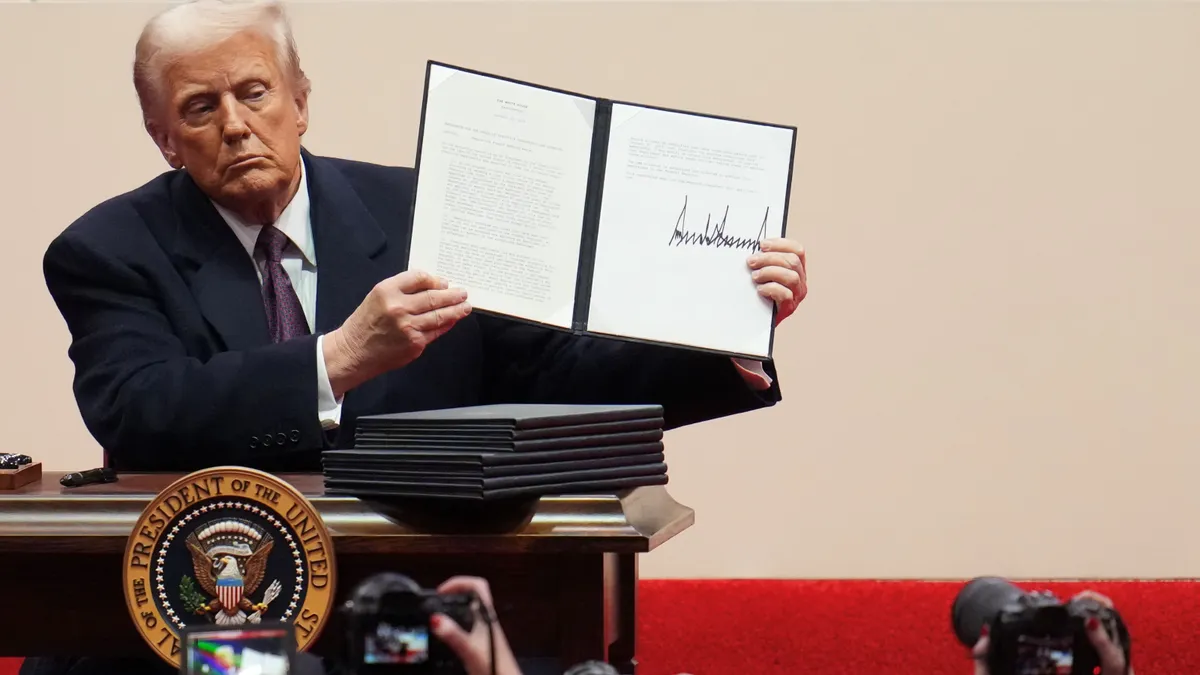

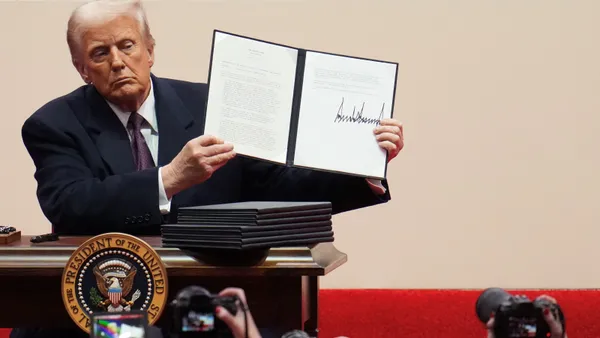

Vaccinations of healthcare workers began in the U.S. this week with the delivery of 2.9 million doses of Pfizer and BioNTech's shot Another 2 million are expected to arrive next week. The initial batch from Moderna will include about 5.9 million doses, U.S. health officials have said. The Trump administration pre-ordered 200 million doses from the biotech, and has an option to buy an additional 300 million.

Distribution is new territory for Moderna, which has spent a decade developing a way to use synthetic messenger RNA molecules to make medicines. Eye-popping fundraising rounds and investor interest in the technology made it one of biotech's flashiest companies. In 2018, Moderna raised over $600 million in an initial public offering, which remains the largest ever for a drugmaker.

Until this year, however, mRNA medicines remained unproven and Moderna's most closely watched candidate was a vaccine for a virus that can cause birth defects. Company shares traded below $19 apiece at the start of January.

But the pandemic proved a defining moment for both Moderna and mRNA-based vaccines, which can be designed and created faster than other types of vaccines. Both Moderna and Pfizer partner BioNTech dove into coronavirus research in January, advancing to human testing within a few months and, with the help of larger partners executed on the fastest vaccine testing program in history.

Moderna is now worth more than $56 billion, as much or more than storied biotechs like Regeneron, Vertex and Biogen. BioNTech is valued at nearly $26 billion.

Ned Pagliarulo contributed reporting.