Cardiologists still see value in Medtronic’s renal denervation treatment even as a recent study failed to prove its renal denervation treatment worked better than drugs alone at reducing patients’ blood pressure at home.

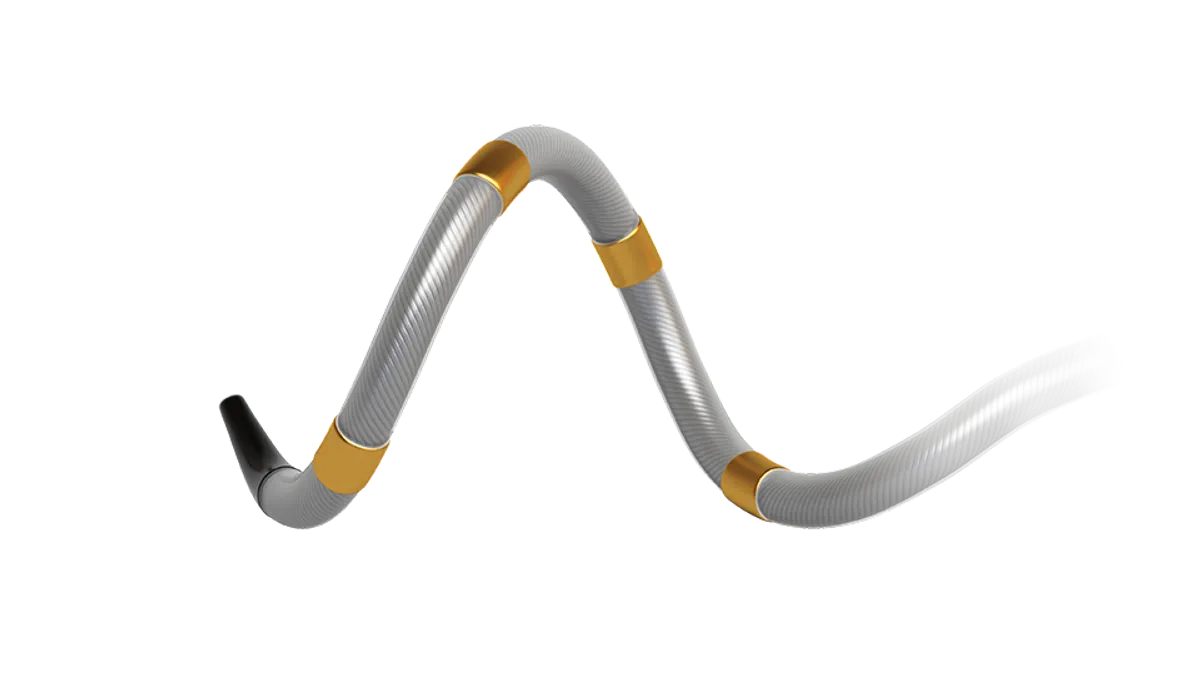

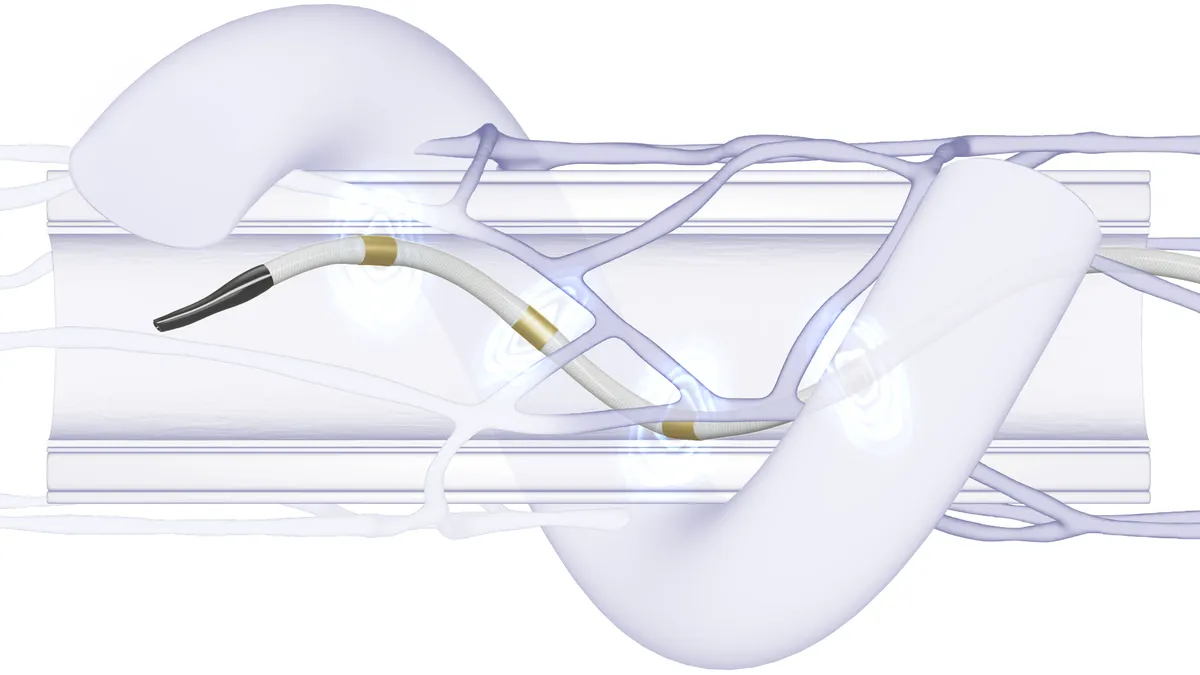

The treatment, which Medtronic recently submitted to the Food and Drug Administration for approval, involves a minimally invasive surgery where electrodes on a catheter ablate nerves in the renal artery to reduce blood pressure. The company shared the results of its SPYRAL HTN-ON MED trial last week, raising questions about whether physicians will use it, which patients will be eligible for the treatment and how insurers will cover it.

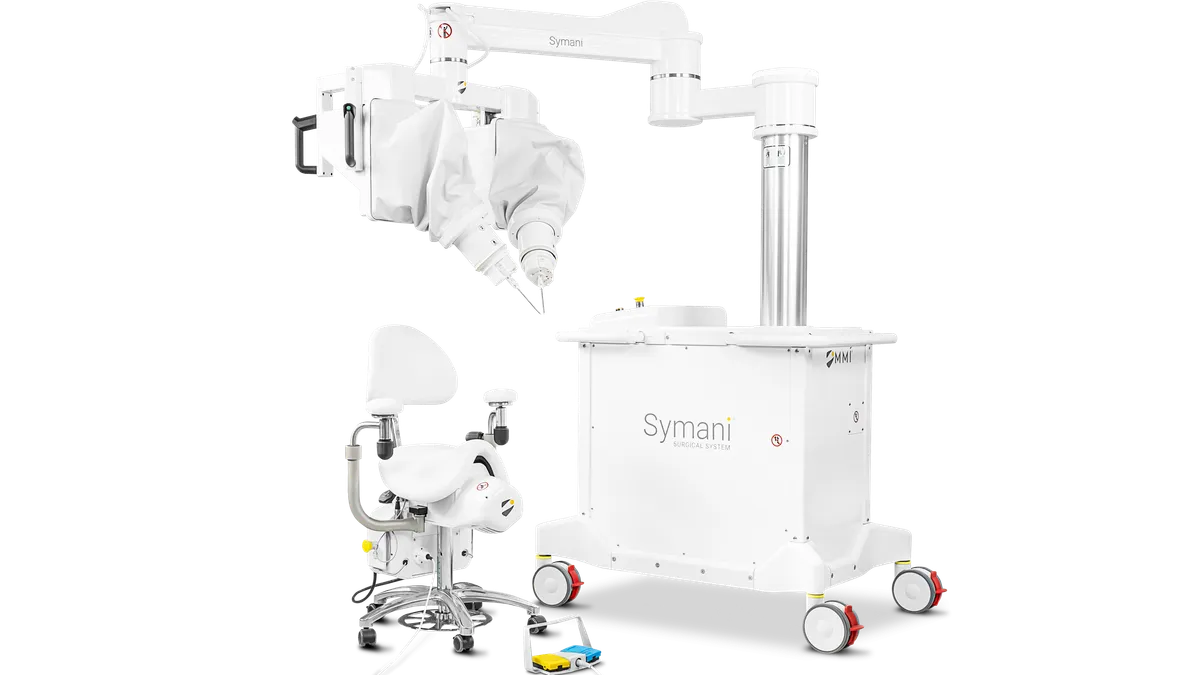

While the trial missed its primary endpoint, renal denervation could still be a viable treatment for patients with high blood pressure, said Dr. David Lee, a professor of cardiovascular medicine at Stanford, who has participated in multiple studies of Medtronic’s Symplicity Spyral system.

“It’s a little disappointing on some level,” Lee said of the trial missing its primary endpoint. “But if you look at the totality of the data, the therapy does work. It’s very consistent, the blood pressure drop that we’ve seen with other studies using this type of technology in renal denervation.”

Medtronic chalked up the lack of a significant difference between the control and treatment groups to patients who received a sham treatment being prescribed more medications during the trial than patients who underwent renal denervation. Conversely, some of the patients who underwent renal denervation reduced their medications during the trial, giving 21.8% of patients in the control group a net change that favors their blood pressure reduction compared to just 1.9% in the renal denervation group, J.P. Morgan analyst Robbie Marcus wrote in a research note on Nov. 7.

“Part of this we want to blame on Medtronic for poor trial compliance, but in the end, we aren’t surprised that doctors just want to properly treat their patients, and if they need a medication change they won’t hold back due to a clinical trial — protocol or not,” he wrote.

The study met its primary safety endpoint, with just two reported adverse events, both vascular complications from renal denervation.

The study’s secondary endpoint, comparing blood pressure measurements taken in a clinical setting, showed the patients treated with renal denervation had a significant reduction in systolic blood pressure. This is notable since blood pressure readings typically are more often taken in a physician’s office than through 24-hour at-home monitoring, Lee said.

“Looking at it from a clinician standpoint, I'd say yes: I think the numbers still support the idea of using renal denervation for patients who can't take more medicines, and maybe they don't even want to, or they're having trouble controlling their blood pressure with medications,” Lee said.

Dr. Randall Zusman, director of the division of hypertension at the Massachusetts General Hospital Heart Center, told Stifel analyst Rick Wise in a Nov. 8 discussion that the results point out how complicated it is to do this type of research.

He added that the data — while yet unpublished — suggest there are “some interesting and valuable findings in the trial that will make renal denervation still an attractive option for certain patient groups.”

Who will be eligible?

As Medtronic seeks FDA approval for the device, questions linger about what patients will be eligible for the treatment. Jason Weidman, Medtronic’s president of coronary and renal denervation, said in an Nov. 7 investor call the company is “very confident in the totality of our data supporting this submission.”

More than 1 billion people worldwide have been diagnosed with hypertension and about 18 million people have a systolic blood pressure above 150mmHg. Medtronic estimates that the treatment would first be used for patients with drug resistant hypertension and blood pressures above 150mmHg, and later expand to patients with blood pressures above 140mmHg. Reaching just 1% of patients in these segments would be a $1 billion market opportunity, the company said.

“I've long learned not to predict what the FDA might do,” Zusman said, adding that the agency may look more closely at the data to see who responded and who didn’t.

The treatment likely would be an option for patients who are resistant to multidrug therapy and have a blood pressure above a certain level, Zusman said. He added he also would like to see the treatment as an option for patients who can’t tolerate multi-drug regimens, but that it’s “far from the point” of being a strategy for people who don’t want to take medication.

“My guess is that it would be more commonly used for people who are on one or two medicines, now you’re starting to think of three, four or five medicines,” Lee said.

Insurance coverage

If the FDA approves Medtronic’s renal denervation device, the next big question may be whether insurance will cover it.

“This is clearly one of the largest barriers and it will take time,” Weidman said, adding that the company has been meeting with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services as well as large commercial payers.

For the CMS, there will likely be multiple routes to coverage, while the company will need to work with private payers, one by one, he said.

Coverage also has been a challenge in Europe, where Medtronic’s Symplicity Spyral system has had a CE Mark since 2013. Many countries require economic value evidence, so Medtronic has several cost effectiveness analyses underway, J.P. Morgan’s Marcus wrote.

In addition, many insurers there follow European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines, which currently recommend that renal denervation only be used in a clinical trial setting. Medtronic is working with physicians to update these guidelines, but the next update isn’t scheduled until 2024, Marcus wrote.

“I'm hopeful that there can be an agreement between the payors and the companies that are in this space to say, ‘listen, we think that this fits here,’” Lee said.