Dive Brief:

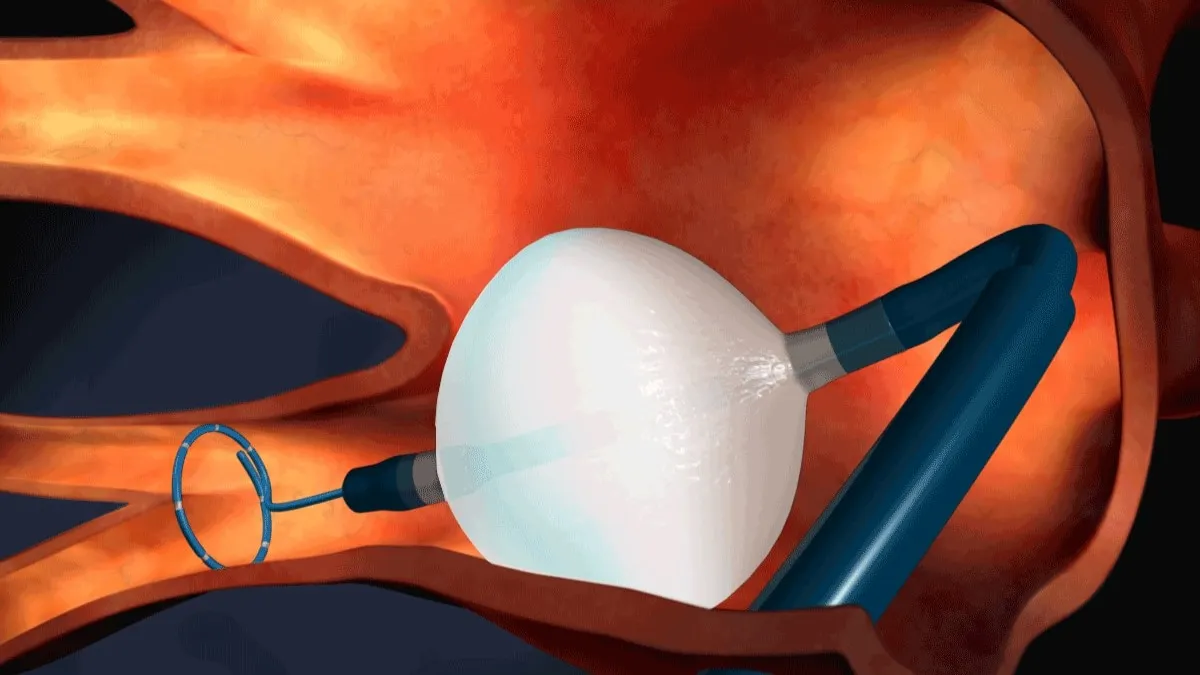

- Using Medtronic’s catheter cryoballoon ablation device to treat paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (AFib) achieved better outcomes than antiarrhythmic drugs over three years of follow up, according to a paper published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

- The paper describes a clinical trial that randomized 303 people to undergo initial rhythm-control therapy with cryoballoon ablation or to receive antiarrhythmic drug therapy. After three years, persistent atrial fibrillation and recurrent atrial tachyarrhythmia were lower in the device cohort.

- Medtronic used the data to make the case that its Arctic Front devices should be used as an early treatment for atrial fibrillation, a setting in which it was authorized in the U.S. last year.

Dive Insight:

Traditionally, patients with atrial fibrillation receive antiarrhythmic drug therapy as an initial rhythm control strategy. The Food and Drug Administration gave physicians another option last year when it expanded the label for Medtronic’s catheter ablation device.

The study reported in the NEJM provides evidence of what happens when patients receive ablation rather than drugs as their initial therapy. Over three years of follow-up, 1.9% of people in the ablation group had an episode of persistent atrial fibrillation versus 7.4% of individuals in the antiarrhythmic drug group. The rates of recurrent atrial tachyarrhythmia, 56.5% versus 77.2%, also favored ablation.

Medtronic’s device delivered better results on other endpoints as well. Patients in the drug cohort spent more time in atrial fibrillation, with median times of 0.24% versus 0.0% for those who received ablation. After three years, eight patients (5.2%) in the ablation group and 25 patients (16.8%) in the antiarrhythmic drug group had been hospitalized. Serious adverse events occurred in seven patients (4.5%) in the ablation group and in 15 (10.1%) in the antiarrhythmic drug group.

Jason Andrade, director of heart rhythm services at Vancouver General Hospital and principal investigator for the study, set out what early treatment with ablation could mean for patients in a statement to discuss the paper.

“In the short term, this may be reflected as less recurrences of arrhythmia, improved quality of life and less healthcare utilization. In the long run, this may translate into reduced disease progression, with subsequent reduction in the risk of stroke, heart failure and premature mortality,” Andrade said.

Andrade was also quoted in a separate statement from The University of British Columbia that framed the study as evidence that it is time to rethink the treatment of atrial fibrillation.