The limited market for pediatric devices has long stymied medical device development for children, prodding regulators, researchers and companies to rethink how to commercialize the devices.

Congress recognized those challenges with passage of the Pediatric Medical Device Safety and Improvement Act in 2007. The law, pushed for by the American Academy of Pediatrics, created a research agenda and bolstered postmarket surveillance for devices used in children.

Despite the market challenges, pediatric device approvals have inched up during the last decade. Of the 66 devices FDA authorized through the premarket approval and humanitarian device exemption (HDE) pathways in 2017, only 18 were indicated for use in a pediatric population, according to former FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, a marginal increase over past years.

But most pediatric disorders do not represent a large enough pool to lure big manufacturers' research and development dollars.

"With pediatric markets, that margin for error is almost zero," James Wall, co-investigator and biodesign lead at the UCSF-Stanford Pediatric Device Consortium said. It is one of five FDA-backed partnerships bringing together health systems and academic or research institutions to support medical devices for children through all stages of development, an idea born from the 2007 legislation.

"If you're going after heart disease or diabetes or even asthma, you can afford to spend a little bit of money and maybe even lose your way a little bit, pivot back, and you still have a big enough market that there's opportunity for technology to be developed on a reasonable amount of capital," Wall told MedTech Dive.

Medtech giant Medtronic is among those able to carry out necessary clinical trials to expand certain product approvals into younger age groups, particularly in the case of its insulin pump system.

"We know based on our current results, kids are not just small adults; they do show different kinds of responses to our therapies," Robert Vigersky, chief medical officer in Medtronic's diabetes group, said in an interview with MedTech Dive.

FDA last year greenlighted Medtronic's 670G in patients as young as 7-years-old, two years after authorizing the device in users 14 and older. The company just published clinical trial data assessing the device in the 2 to 6-years-old age group in its pursuit of an even younger indication.

And asthma detection startup Tueo Health, an alum of Stanford's biodesign center that Wall now leads, recently was acquired by Apple.

The University of California, San Francisco was a member of FDA's inaugural class of pediatric device consortia, or PDCs, when the program launched in 2009.

During its most recent round of grants, FDA awarded around $6 million over five years to each of the five consortia members. The other four members are based in Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, Houston and Los Angeles. That funding supports a "stable of consultants," Wall said, who helps interested parties with everything from clinical trial design and prototyping to FDA submissions and reimbursement strategies.

The next round of funding could be more generous; the House Appropriations Committee earlier this month said it "is concerned the CDRH does not have the necessary resources to properly leverage the benefits of the PDC program" and recommended allotting an additional $1 million to the program to "improve infrastructure for conducting pediatric device trials."

"It's not enough to develop a full, [late-stage] medtech company," Wall said. "But it is enough to seed early stage good ideas to at least direct them to the point that they made and be competitive to get venture funding."

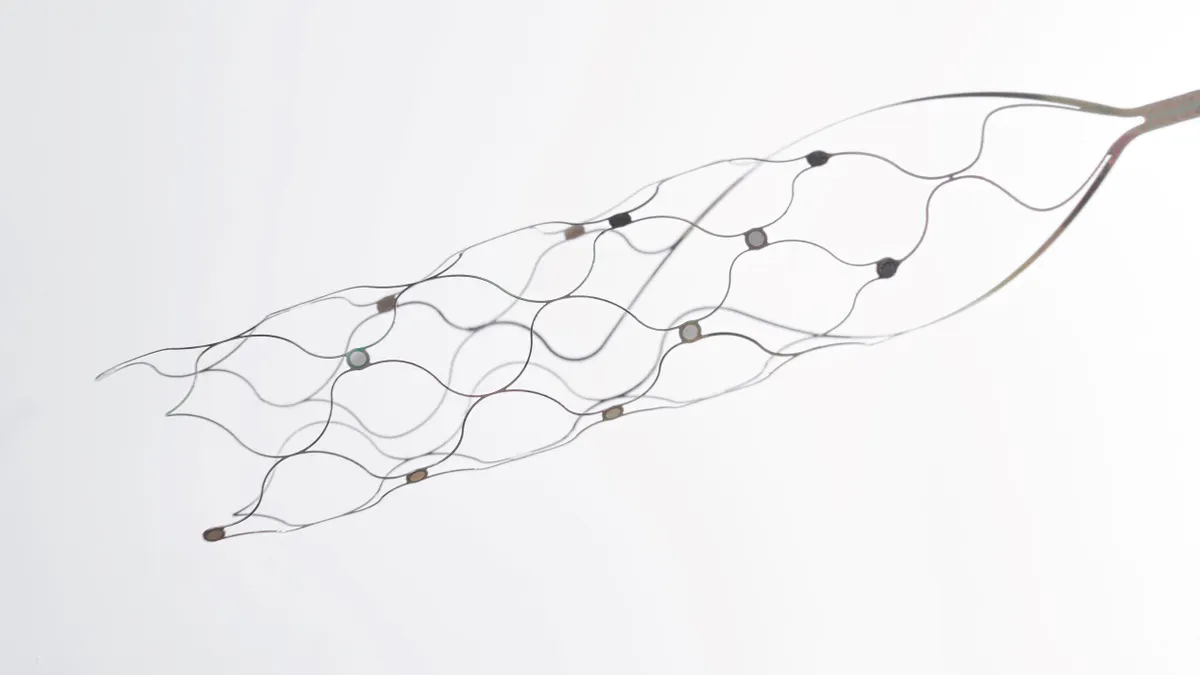

This year, the Bay area program's pitch competition funded technologies including a gastrostomy button securement device, a nasogastric feeding system, and a wireless tracheostomy alarm and respiratory monitoring system. To date, the UCSF consortium reports they moved 10 internally developed devices into first-in-human trials, winning $30 million in funding for those technologies.

Taking a cue from orphan drugs

Small molecule drugmakers targeting disease areas with fewer than 200,000 patients receive certain fee waivers, tax breaks on R&D expenses and seven years of market exclusivity.

There might be lessons from pediatric drug development to apply to devices, UCSF's Shuvo Roy, co-investigator and technology lead, said.

"The pediatric market is always going to be small in some scale … and that’s okay," Roy said. But incentives "to encourage that last mile development for pediatric devices toward commercialization" like tax breaks or better reimbursement rates could help, he said.

AdvaMed wrote a letter to FDA last fall with suggestions to lower the risk in developing devices for children. The list included designating more pediatric technologies as breakthrough devices, developing pediatric-specific device review teams within the agency, allowing for real-world evidence and adult trial extrapolation to support pediatric device applications, and requiring Medicaid to cover all pediatric device trials with a 90% federal match.

The device lobby also proposed a separate orphan regulatory pathway for devices targeting "super-small" pediatric populations not likely to be served by the HDE program.

In the meantime, UCSF and Stanford are aiming to make the process less risky.

Wall gave the example of Stanford Biodesign-born company Novonate, which makes LifeBubble, a device designed to secure umbilical cord catheters while protecting the insertion site. He noted the team was able to develop the product within Stanford up to the point of being ready to manufacture.

"At that point, there was so little risk left in the product that a venture group was willing to put in a small amount of money that they could expect to see a return on," Wall said.

Aside from helping new devices go from idea to prototype to product, the UCSF-Stanford partnership can incentivize companies to move pediatric use from off-label to on-label, Wall said.

The lack of devices specifically indicated for children means there is rampant off-label use of adult devices in children. But, given the paucity of pediatric devices currently on the market, "it would be malpractice not to use them," Wall said.

In the most recent round of funding, FDA offered additional grant money to PDCs interested in carrying out a real-world evidence projects.

"The data is being generated every day in clinical care, so there's no good reason not to use that data and analyze it properly," including in pediatric populations, real-world evidence hub NESTcc Executive Director Rachael Fleurence told MedTech Dive. "There really is a dearth of data for pediatric devices, so that is a critically important area for something like NEST to be operating in."

In the case of Stanford and UCSF, the project involves mining data from EHRs, mobile health applications and connected sensors to assess safety and effectiveness of a cryoablation probe in adolescent patients undergoing sunken chest repair.

Wall believes FDA is "very supportive" of the idea of real-world evidence being used to justify indications in kids.

In addition to the RWE project, Wall said his PDC is having conversations with medical device manufacturers whose products for adults could be used in children but that simply haven't been tested or adapted appropriately.

"We're beginning to work with those companies to say 'we'll decrease the friction and help you get the clinical evidence you need to have an indication,'" Wall said.