Dive Brief:

- Clinical trials studying new methods for knee cartilage regeneration often exclude people with common traits such as osteoarthritis or being above 55 years of age in favor of patients most likely to come through the procedure with the fewest complications, according to a review by Penn Medicine researchers.

- The authors suggest that once the safety and efficacy of a therapy is established, clinical trial teams should consider evaluating the treatment in wider populations who could benefit from cartilage repair to conserve their joints as an alternative to full knee replacement.

- The American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine and the National Institutes of Health provided funding for the study.

Dive Insight:

Total knee replacements greatly outnumber the volume of knee cartilage repair procedures performed annually. Yet the Penn researchers believe many in the broader patient population could benefit from new joint repair techniques.

The patient populations affected by different knee conditions are larger than those included in clinical trials studying new cartilage repair techniques, the researchers said.

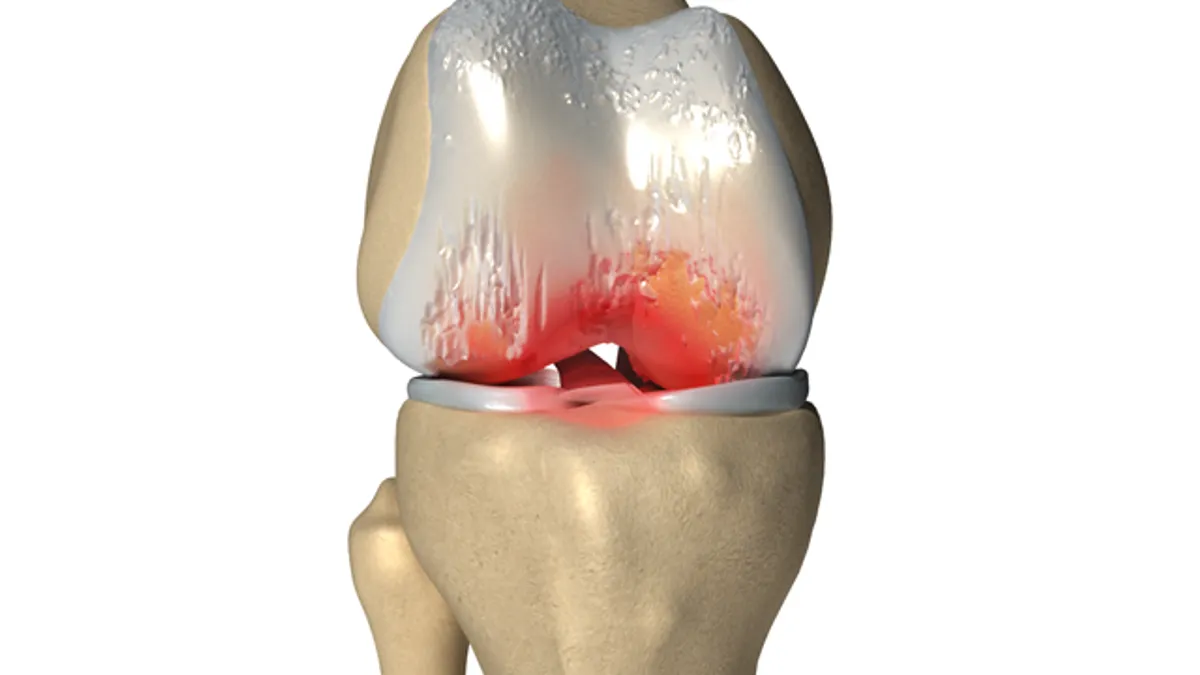

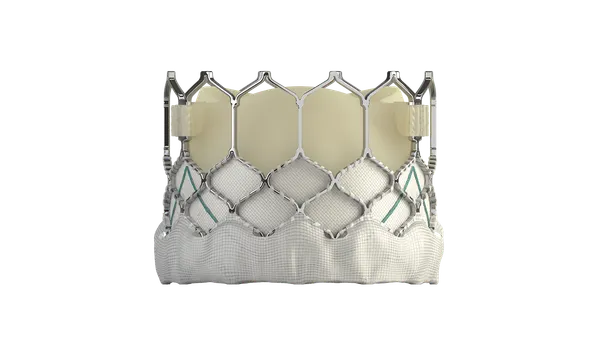

New cartilage regeneration approaches include matrix-associated autologous chondrocyte implantation (MACI), and autologous matrix-induced chondrogenesis (AMIC). In the MACI procedure, healthy cartilage cells are harvested from the patient, seeded in a collagen matrix and then reimplanted. In AMIC, a cell-free collagen matrix is implanted.

The treatments have shown improved outcomes compared to traditional techniques known as chondroplasty and microfracture, but they've been restricted to patient populations with optimal conditions for surgery, the study authors said.

More inclusive study designs would better reflect the broader population in need of treatment and provide doctors with context on which conditions could benefit most from new therapies, said study co-senior author Robert Mauck, a professor of orthopaedic surgery and director of the McKay Orthopaedic Research Laboratory at Penn Medicine.

Some regeneration therapies have shown promise in patients with more challenging conditions, the researchers said. For example, a technique to clear out cells that have stopped dividing could lead to better results in patients older than 55, and 3D-printed tissues offer an alternative to full knee replacement in patients with larger lesions.

"We challenge the orthopaedic field to think about whether therapies could work for patients other than the 'perfect' candidate. And if these therapies don’t work for those groups, what can we do, as an alternative, to help them?," Mauck asked.

The researchers evaluated 33 cartilage repair clinical trials from the ClinicalTrials.gov database. They found that 79% excluded patients with osteoarthritis, and half excluded patients over 55 years old or under 18. Almost 60% excluded patients for having lesions greater than eight square centimeters in size, and 64% excluded patients with more than one cartilage lesion.

"We want to provide more patients with the opportunity to repair their joint instead of defaulting to completely replacing it," James Carey, an associate professor of Orthopaedic Surgery and director of the Penn Medicine Center for Cartilage Repair and Osteochondritis said. "Having more clinical data on a wider range of factors will spur more innovation and open up the door for a variety of ways to repair joints."