Some in the device industry are pushing back against proposed FDA label changes to breast implants, including an acknowledgement of "breast implant illness" and a recommendation that device makers continually update risk information based on the latest postmarket findings, in comments among more than 1,200 submitted.

FDA issued draft guidance on breast implant labeling in October following a public advisory committee meeting in March on the devices, which have been linked to a type of lymphoma and a constellation of other symptoms, saying it "heard loud and clear … that there is a distinct opportunity to do more to protect women who are considering breast implants."

The agency outlined potential language for a boxed warning, patient decision checklist, patient device card, rupture screening recommendations and description of materials. Its federal docket closed Dec. 23.

As public awareness of the lymphoma and other breast implant risks has increased during the past several years, patient interest in implantation appears to have remained strong. Breast augmentation remained the top plastic surgery procedure in the U.S. between 2006 and 2018, the year for which the American Society of Plastic Surgeons last reported data.

Some weighing in, like The American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, argued against a new boxed warning on grounds that patients do not come into contact with implant packaging. The group supports new tools to clarify patient goals, introduce decisions to be made prior to surgery, and outline short and long term financial responsibilities.

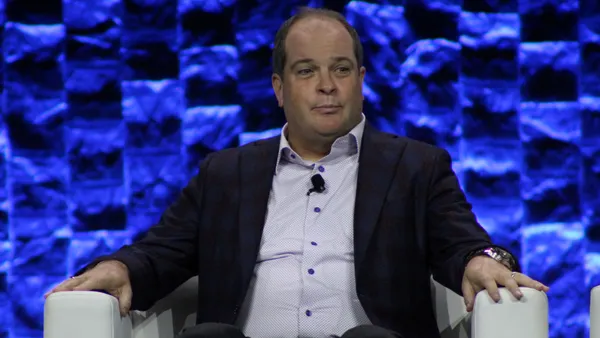

The Medical Device Manufacturers Association said adverse reactions should not be described as breast implant illness but as "systemic symptoms" in the draft guidance, and wants the language cut entirely from a potential boxed warning.

"[I]t is misleading to refer to these symptoms generally as 'breast implant illness' when this term is not used or accepted in clinical practice," MDMA President Mark Leahey wrote in comments to FDA.

MDMA said because systemic symptoms are "not serious or life-threatening," they should not be part of a boxed warning.

"Moreover, the lack of definitive clinical (or nonclinical) data confirming likely association between breast implants and these systemic symptoms further counsels their removal from this portion of the patient and prescriber labeling — the risks of potential systemic symptoms as reported in the literature can be given the proper context in other portions of the labeling," Leahey added.

Conversely, patient groups and some other surgeons want the FDA to beef up the proposed boxed warning.

A comment jointly submitted by a working group with representatives from the National Center for Health Research, plastic surgeons and patient advocates urged FDA to follow through with requiring a boxed warning, but said its current form is "too vaguely worded." The group said the language ought to "be more explicit about the evidence regarding breast implant illness instead of making it sound like it is not a real risk."

"It refers to systemic symptoms, which is the correct term, but not one that all patients would understand. It does not mention breast implant illness, which although not an established medical term, is one that is well understood by patients," the joint comment said. The group also noted the proposed black box language does not mention potential risk of autoimmune of connective tissue diseases.

That group submitted its own sample patient checklist to FDA in October, endorsed by groups like the National Women's Health Network and 77,000 signatures. The goal is to share "the most essential information that patients might not get from standard informed consent forms," focusing less on the cosmetic and surgical risks that patients are more likely to become aware of in the lead-up to surgery.

MDMA is also pushing for changes to how the proposed warning describes cancer-related deaths. In FDA's example boxed warning, the agency proposed writing that "Some patients have died from BIA-ALCL." MDMA wants that to change to, "In the cases where BIA-ALCL has spread beyond the scar tissue and fluid near the implant, rare cases of death have been reported."

The industry group also said FDA's proposal that manufacturers regularly update risk info based on collection of new data and further postmarket experience is "impracticable" and "would significantly alter the well-established processes that provide for effective post-market analysis, reporting, and product updates according to existing statutory and regulatory requirements." MDMA instead thinks each manufacturer should be required to update the incidence of BIA-ALCL on a yearly basis, which the group said would ensure uniform reporting across device makers.

In regard to implant materials, MDMA proposed eliminating FDA's "misguided" recommendation that a patient information booklet or brochure include an easy-to-understand yet detailed description of the composition of filling and shell. "Placing detailed device description information in patient labeling defeats the 'patient friendly' intent of the Draft Guidance and stands to cause more confusion than clarity by providing information outside the context of the full prescribing information," MDMA said.

In its draft guidance, FDA recommended asymptomatic patients with breast implants undergo ultrasound or MRI screening five to six years after implantation, and every two years thereafter, to check for silent rupture. The new inclusion of ultrasound comes despite a lack of established, validated ultrasound test for rupture, MDMA said.

"Although ultrasound provides promise, there is insufficient data to support recommending ultrasound be the primary means for detecting silent rupture at this time. MDMA recommends keeping MRI as the primary means for detecting silent rupture to avoid questions regarding ultrasound data reliability on this important issue," the group wrote.

The American College of Radiology backed up that rebuttal, saying FDA's proposed recommendations "differ significantly from ACR recommendations."

"The ACR maintains there is no role for ultrasound (US) in evaluation of silicone implants in asymptomatic patients given scarcity of data. And given the limited data and meta analyses of several studies, there is no clear role for MRI without contrast in evaluation of silicone implants in asymptomatic patients."

This story has been updated to make clear that the plastic surgeons who were part of the joint working group and also had ties to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons did not represent the society in the joint comment.