Dive Brief:

- Implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) devices are underused in women and racial minorities with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), according to a Mayo Clinic study.

- The study looked at 23,535 adult hospitalizations from 2003 to 2014 for HCM, a disease characterized by abnormally thick heart muscle that can cause sudden death. Over that period, ICD use among women was 12.8%, compared to 22.7% in men.

- In a statement released Tuesday with the study, Sri Harsha Patlolla, one of the authors of the study, said sex-specific differences in HCM care could be the result of "systemic bias with inequity of clinical care." Patlolla added that limited access to specialized care may be impacting patients as well as "ICD use is more common in large and teaching hospitals."

Dive Insight:

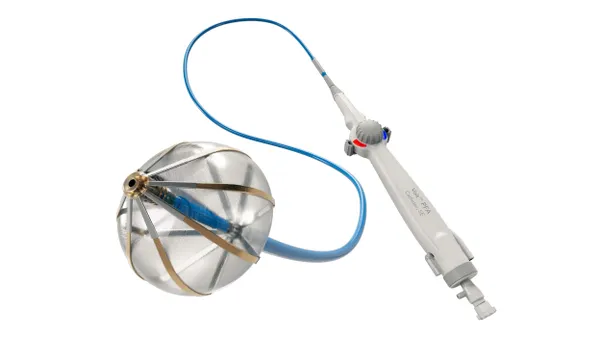

ICDs are used in HCM patients to reduce their risk of sudden cardiac death. Current HCM guidelines recommend the use of the devices in patients with recognized risk markers or modifiers for sudden cardiac death. Research dating back to 2007 has shown sex and racial differences in the use of ICD, leading the Mayo Clinic researchers to assess the situation in HCD.

Writing in Mayo Clinic Proceedings, the researchers describe an increase in the proportion of people who received an ICD, which rose from 11.6% in 2003 to 17% in 2014. However, that overall figure masks differences between different groups of patients.

ICD use in women was 7.7% in 2003, compared to 20% in men. Use of the devices in women grew over the analyzed period, rising to 12.9% by 2014, but with use in men ticking up to 22.5%, a large disparity remained. Jeffrey Geske, a cardiologist at the Mayo Clinic and co-author of the study, offered a potential explanation for the disparity.

"It is possible that focusing on symptom management shifts focus away from sudden death risk assessment in women more than men, and shared decision-making may result in different choices between sexes. In combination with current findings, these suggest a need for providers to recognize sex-specific differences in outcomes and management trends in women with [HCM]," Geske said.

Meanwhile, non-white patients had lower adjusted odds of receiving an ICD, leading the researchers to suggest that "differential access to advanced care and possible provider bias" may limit use of the devices. From 2003 to 2008, the percentage of white patients hospitalized with HCM who received an ICD was higher than for other races. However, the disparity faded over the second half of the study.

Outcomes differed by sex and race, too. The researchers found women and non-white hospitalizations had higher rates of device-related complications, longer lengths of in-hospital stay and higher hospitalization costs. Steve Ommen, medical director of the Mayo Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Clinic, said the findings raise a range of questions.

"Why are patient outcomes different based on sex and race? Does this reflect an inherent bias, or is it the result of underlying differences in disease expression? As further studies are pursued, providers should seek to eliminate potential bias in ICD decision-making, given the known mortality benefit associated with appropriate ICD implantation," Ommen said.