Hospitals are readying for Jan. 1, when they expect they will have to publicly disclose the negotiated prices they reach with insurers for services performed inside their facilities — barring any intervention from a federal appeals court.

Despite facing an extraordinary difficult year due to the coronavirus pandemic, many hospitals are moving toward, or are ready, to comply with posting prices online, compliance experts said. But some in the industry are skeptical as to how useful that information will be for consumers and whether it ultimately bends the cost curve in America.

A chance still exists the rule is blocked before it can be implemented. The hospital lobby is hoping a federal appeals court will rule in its favor and bar the rule from taking effect at the first of the year. It's unclear when a final ruling will be delivered by the three-judge panel, but they seemed highly skeptical of the hospital lobby's petition against the transparency rule during oral arguments in October.

"What I'm finding is that most of my clients are prepared," said Delphine O'Rourke, a partner at the firm Goodwin. If not, they just need refinement around the edges, O'Rourke added.

Other compliance experts said hospitals and health systems are moving more quickly toward compliance as the new year edges closer, and as it seems unlikely the administration will push back the requirement like some had previously hoped.

"People are really starting to move towards compliance. I think they realize that it's here to stay," said Becky Greenfield, an associate attorney with Wolfe Pincavage.

What can consumers expect?

The policy requires hospitals to share two streams of information. First, hospitals will have to share a machine-readable format of its negotiated prices with every insurer and every insurance product — a sizable pool of information.

Then they will also have to prepare a list of 300 "shoppable services." A total knee replacement would be a good example. It's a procedure a consumer likely has time to plan and prepare for, unlike an emergency surgery due to an accident or failing health. The idea is to provide the price information so consumers can shop around for the best deal.

The regulation requires the "shoppable" list to be consumer friendly and will likely be the most useful for consumers, unlike the machine readable list, which will likely be of interest to researchers and those within the industry, Greenfield said.

These lists and how they are presented are going to vary from facility to facility, O'Rourke said. There's no requirement on where systems place these on their websites. That's similar to 2019, when hospitals had to post their initial charges online, or the prices before any negotiations with insurers. Hospital could bury it on their websites.

The fine if hospitals fail to comply is $300 per day, but CMS has not outlined any plans for monitoring adherence to the requirement.

"Hospitals are generally very compliant. They are rule-following organizations. That's the culture," O'Rourke said. But it may be hard for some rural facilities to meet the deadline as they're hard pressed by the pandemic.

Will it be useful?

Some experts are skeptical of whether the deluge of data with help consumers.

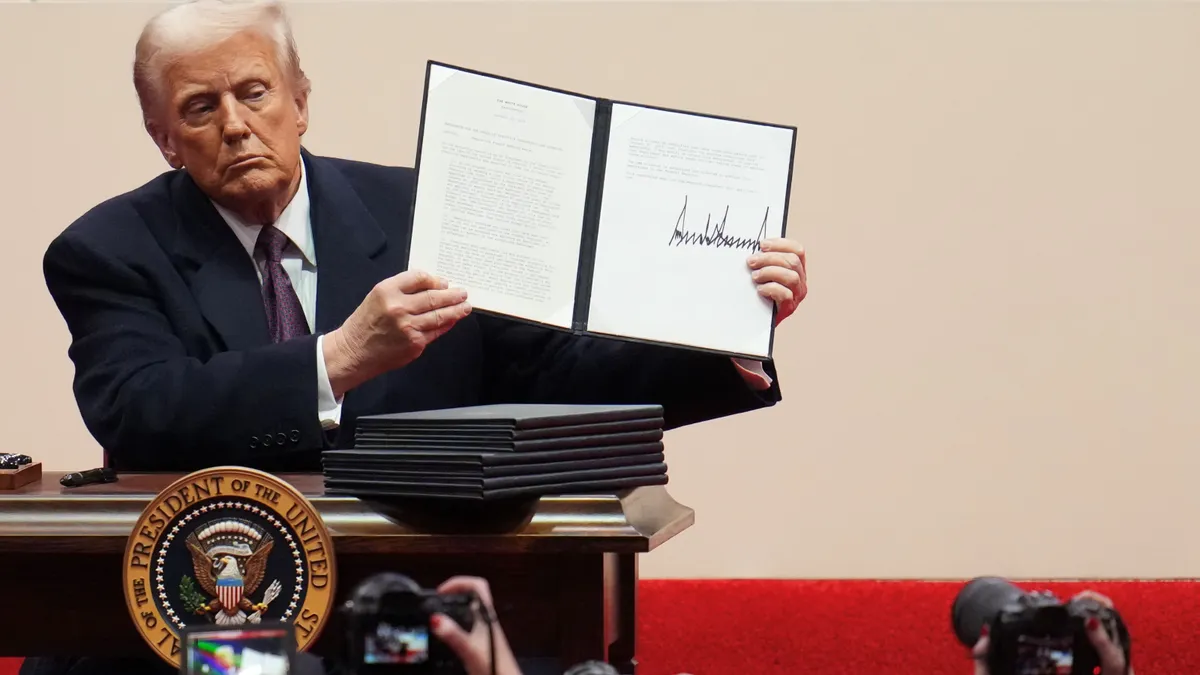

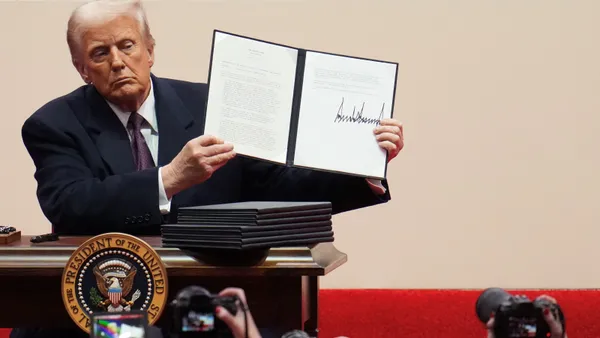

President Donald Trump's administration argues that injecting transparency into America's notoriously opaque healthcare system will help patients. In 2019, CMS released its proposal to require hospitals to reveal the prices they reach with insurers. The administration argued that by arming consumers with pricing information it would enable them to shop around for care, choose less expensive options and ultimately bend the cost of care.

American patients have more "skin in the game" than ever before as high-deductible plans cover more Americans than they did just a decade ago, according to data with the Kaiser Family Foundation. With high-deductible health plans, patients spend their first dollar on healthcare services before coverage kicks in, which some argue incentivizes them to shop for the most cost-effective care.

"If you're going to argue that people have to have skin in the game, which is high deductible health plans, you need to give them and incentivize them with tools that they can use," said Stephanie Kennan, senior vice president of federal public affairs at McGuireWoods Consulting. Kennan previously served as a senior health policy adviser to Democratic Sen. Ron Wyden of Oregon for a decade.

What might be most helpful to consumers is a price estimator tool, which has the potential to help patients gain a reliable estimate without providers having to share the exact price, Greenfield said. This estimator tool is an option hospitals can use to come into compliance with the 300 "shoppable services" requirement.

"Instead of just dumping data, you can create this tool so that a person only learns the information that they need to know to make a decision," Greenfield said.

By compiling all the insurance products and pricing information, the price estimator tool would be able to spit out the out-of-pocket cost a patient is responsible for given the tool would have the benefit design information loaded in.

"My experience is that many hospitals are adopting that," Greenfield said. "In my mind, that's the best of both worlds. You're not disclosing negotiated rates, which no one wants to do. But you're delivering something that is maybe not perfect, but is a good estimate for what the patient is actually paying for the services."