Hospitals are racing to prepare as top U.S. health officials warn the spread of the coronavirus will only ramp up in coming days. That includes checking supplies of personal protective equipment, as the FDA this week took steps to free up the supply chain.

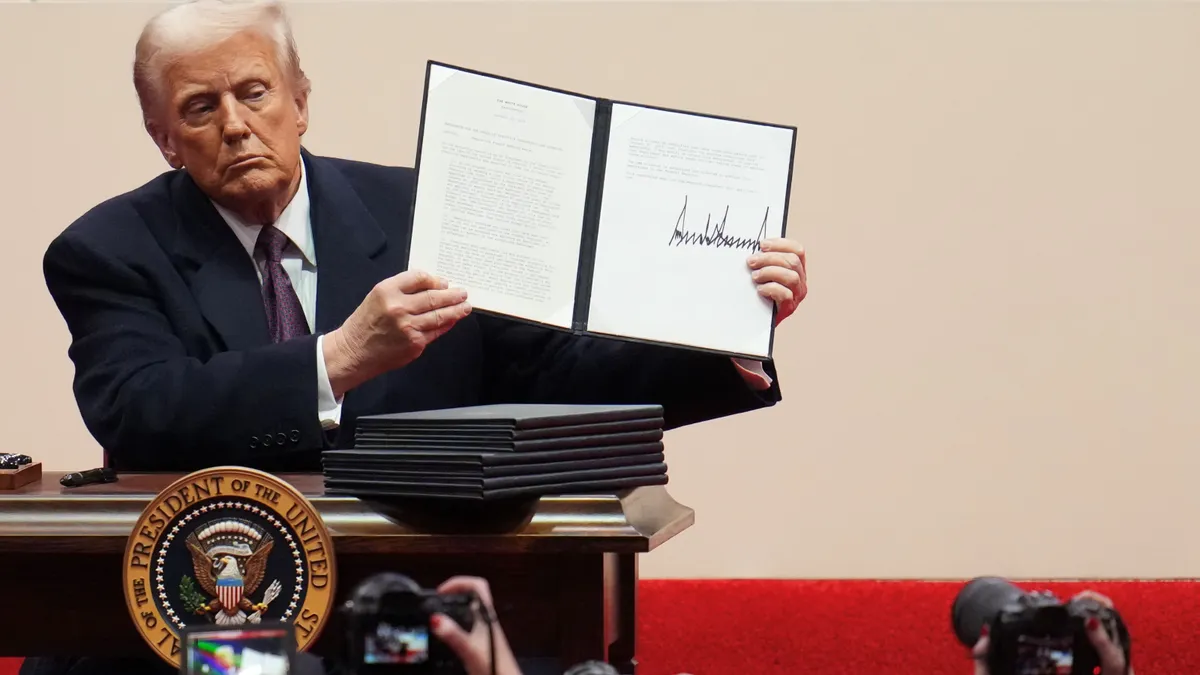

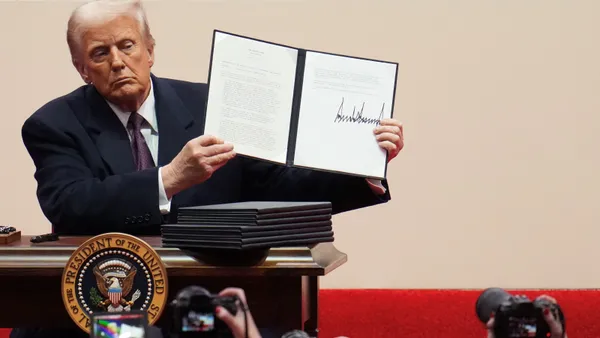

The American Hospital Association is asking Congress for an additional $1 billion, on top of $2.5 billion sought by the Trump administration, to "swiftly provide supplemental emergency funding directly and specifically to support the urgent preparedness and response needs of hospitals, health systems, physicians and nurses on the front lines of this outbreak."

One of the biggest health system group purchasing organizations said it is getting barraged with calls from its members to get updates on clinical guidelines and potential supply chain interruptions.

"I can tell you my phone rings nonstop," Soumi Saha, senior director of advocacy at Premier, told Healthcare Dive. The GPO has 4,000 member hospitals.

In the short-term, facilities are checking inventory and supply chains for key devices like masks and ventilators. Looking further out, some may have to reassess vendor relationships and disaster response planning. Those that are poorly prepared could pave the way for increased consolidation if bottom lines are hit hard, experts said.

The FDA responded to some of these concerns Monday by taking action to make more respirators available for healthcare workers on the front lines. The agency granted the CDC's request for an emergency use authorization that will allow respirators, including N95 masks, typically used in industrial areas like construction to be used in healthcare settings during the outbreak.

FDA said it "is not currently aware of specific widespread shortages" of personal protective equipment but expects the supply chain for the devices to "continue to be substantially stressed" and "under the circumstances of this emergency, nationwide shortages are anticipated."

Hospitals are reviewing plans in anticipation of the number of U.S. cases shooting up, including where overflow patients would go. As of Tuesday, reported cases in the U.S. topped 100, and the number of related deaths tripled to six. At the same time, these numbers likely underestimate the impact, as testing is limited at this point.

A major focus for facilities is ensuring they have enough personal protective equipment (PPE) for providers during disease spread CDC has characterized as "inevitable."

FDA said last week no shortages of essential medical devices had been reported, but acknowledged several manufacturing facilities in China had been adversely affected.

Saha said Premier has been advising hospitals it works with to make sure they have needed PPE on hand but is cautioning against hoarding. "We're very mindful we don't want to see an uptick in ordering absent a true reason to do so," she said.

A few hospitals have reported falling below the recommended two week supply of PPE since the outbreak began, but those were resolved and the vast majority of hospitals are on safe ground for the moment, Saha said.

Premier conducted a survey among its members to determine what they had on hand for supplies like masks, gowns, isolation kits and gloves. It found 86% of hospitals said they are concerned about their supply of PPE and more than half have initiated conservation protocols.

The data will be further analyzed to help better determine when the supply chain could hit a tipping point and in what regions.

The U.S. has two manufacturers of N95 masks — 3M and Prestige Ameritech — that source all raw materials from within the country, Saha said.

They typically produce about 2 million masks a month but can double production during high demand.

It takes 30 to 60 days to reach those levels, however. A spike in use before that happens could cause trouble if overseas mask production remains halted.

"That is where we're concerned that U.S. manufacturing alone cannot sustain a true outbreak in the U.S.," she said. A shortage of ventilators is also a concern, as the CDC has reported some patients require mechanical ventilation.

Premier has also been monitoring labor demand, but hasn't yet heard of hospitals with staffing shortage concerns.

Still, hospitals should be prepared for that, Monica Hon, vice president of healthcare consultancy Advis, told Healthcare Dive. They can start now by determining what providers can be on call and when. It's a good idea for hospitals and practices to make sure they have a pool of providers, in particular nurses, if they need to ramp up staffing because of high patient volumes or sick employees.

FDA reported Thursday supplies of an unnamed drug have run short in the U.S. because of problems tied to spread of the virus.

But Saha is not concerned of widespread shortages of necessary drugs, although that could change if Chinese manufacturing is shut down for an extended period or the outbreak intensifies in Europe.

Manufacturers of finished drug doses report four to six months of API on hand, she said. "We believe we are in a good place for at least the next 90 days, and that's being conservative," she said.

One problem is a dearth of information, particularly in China. Saha would like to see more mandated reporting from global manufacturers facing possible shortages.

"One of the big concerns right now is the lack of transparency and visibility in the drug supply chain," she said.

Other forms of disruption

Hospitals and health systems that have outsourced services offshore will be especially vulnerable, Steven Shill, national leader at advisory firm BDO, told Healthcare Dive.

More companies have moved financial and billing functions offsite and those could be disrupted, for example.

It's difficult to say yet what the financial consequences might be, but Shill's sense is that it could be severe, especially for smaller hospitals without much cash on hand. If those facilities are tipped to a breaking point in part because of an increased outbreak, it could lead to more consolidation for the sector.

"I think it paves the road once again for players within the industry that are looking with a fresh set of eyes," he said. "This is just another shoe that's fallen. It's going to take its toll on the industry — on an already fragile environment."

Health systems previously in the line of disasters like hurricanes of recent years in Florida and Texas have seen firsthand the need to reduce geographic concentrations along the supply chain. All should be vetting vendors carefully and evaluating supply chains for sufficient redundancy, Shill said.

"We're going to feel this thing and it's not going to be pretty," he said. "And we should have heeded the warning signs, albeit much smaller."

What hospitals are doing

One of the first hospitals to treat a coronavirus patient was Providence Regional Medical Center in Washington state.

Rebecca Bartles, executive director of system infection prevention at Providence, told Healthcare Dive the health system had geared up its preparation and response levels as the outbreak spread but felt ready for coronavirus after exercises based on previous outbreaks of Ebola and H1N1.

Right now, the system has all the supplies it needs but is anticipating hiccups in the supply chain. "We can fully expect supply issues to be strained," she said.

Providers must meet fairly stringent federal and state requirements for disaster preparedness, including setting aside funds and having guidelines prepared in the case of a pandemic. Test runs are also required, but can be on a variety of scenarios, so many facilities will likely not have drilled for a pandemic in years, Hon said.

Right now, hospitals and health systems should be reviewing those plans and making sure staff are acquainted with them. That will include finding where an influx of patients would be treated, what infection protocols are necessary and how to update local and state public health officials.

Smaller and rural hospitals will have plans in place for getting patients to larger facilities or other designated areas.

Hospitals also have a role to play in public education, she said.

"Beyond the requirements, I think communication and communicating to your community at large to try to prevent the spread of infection is probably the best thing you can do," Hon said. "That seems pretty simple, but you'd be surprised."

Samantha Liss contributed reporting.