Dive Brief:

-

The FDA has published draft guidance for developers of medical devices and other interventions to treat osteoarthritis.

-

The guidance details the FDA’s position on the use of structural endpoints that track changes in the underlying disease, not just the measurement of pain and impediments suffered by a patient.

-

Officials want to see structural endpoints used that track the actual disease's progress but think more research is needed to tie the measures to clinical outcomes.

Dive Insight:

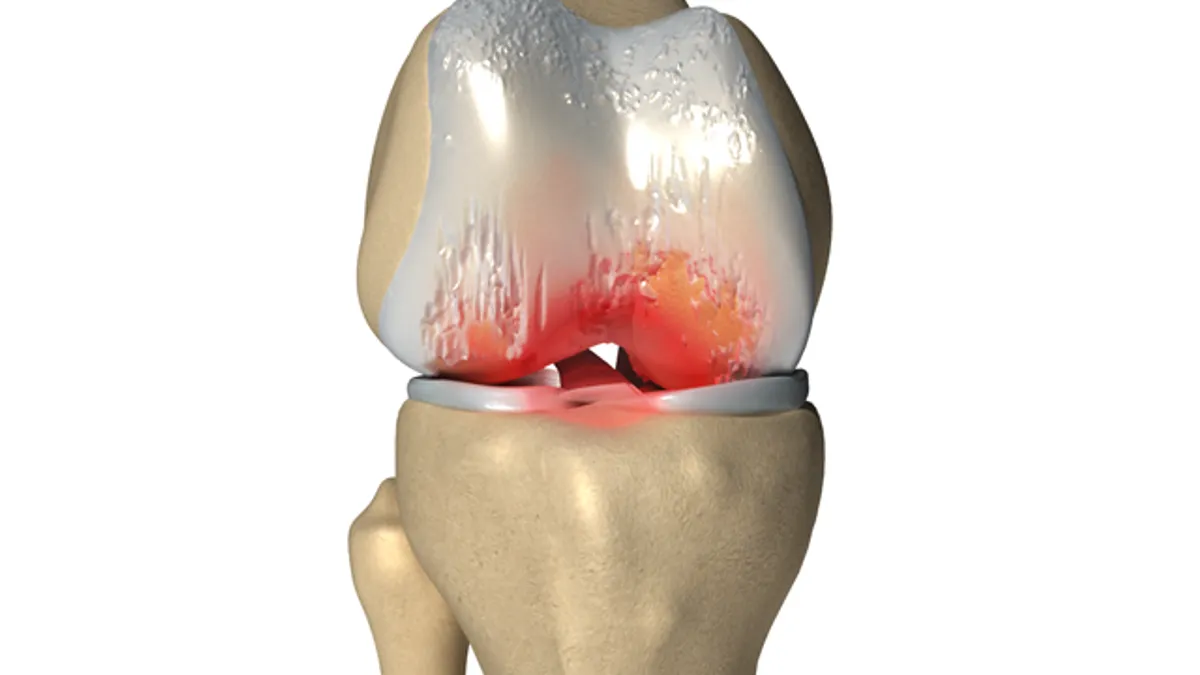

To date, treatments for osteoarthritis have come to market on the strength of data showing they can reduce the pain experienced by patients and enable them to lead more active lives. Though improvements on these patient-reported outcomes are important, they can be achieved without stopping structural damage or affecting the underlying pathophysiology. Patient can feel better while their joints worsen.

The FDA thinks the lack of products targeting the root causes of osteoarthritis represents an unmet medical need. If developers of devices and other medical interventions are to address this need, they will need structural endpoints against which to assess the efficacy of their products.

The FDA’s draft guidance is a step toward the establishment of structural endpoints but shows there is a lot of work still to be done. While some guidance documents mark the culmination of the FDA’s thinking on a topic, the osteoarthritis text is more of a launching off point for talks about structural endpoints with sponsors, academics and the public.

As such, the document is better at framing the problem than offering solutions. The guidance states the complexity of osteoarthritis, the weakness of the link between structural changes and symptoms and the lack of definitions of disease progression underpin the absence of structural endpoints. These factors mean it is unclear what structural changes would translate into clinical efficacy, making it impossible to establish meaningful endpoints without further research.

The FDA will only accept a new measure when it has “substantial confidence ... that an effect on the candidate structural endpoint will reliably predict an effect on the clinical outcomes of interest.” The agency pointed to data from randomized controlled trials and analyses of the disease process and a product’s mechanism of action as examples of evidence that could give it that level of confidence.

That high bar set by the FDA means the osteoarthritis community has work to do before structural endpoints are used to secure regulatory authorizations. The FDA is open to working with researchers to advance the field.