While healthcare policy efforts have focused on data sharing between electronic health record (EHR) systems, they have overlooked fragmented data in medical devices, contend researchers, who want to see an agency initiative address the problem head on.

FDA has made the case that medical device interoperability, the ability to safely, securely and effectively exchange and use information among one or more devices, is critical to patient care and reducing errors and adverse events. The agency has also argued that standards are important to the development of reliable interoperable devices from different manufacturers which could lead to new models of healthcare.

However, critics say FDA has not gone far enough in pushing for conformity to medical device interoperability standards.

FDA should encourage the development of an initiative to harmonize medical Internet of Things (IoT) devices to drive the interoperability of medtech products, according to several academics. The authors of an opinion piece published earlier this month in JAMA Health Forum envisage effective medical device interoperability improving healthcare by "enhancing productivity with actionable data."

Researchers from the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Columbia University and The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine set out the current situation and why and how it needs improving.

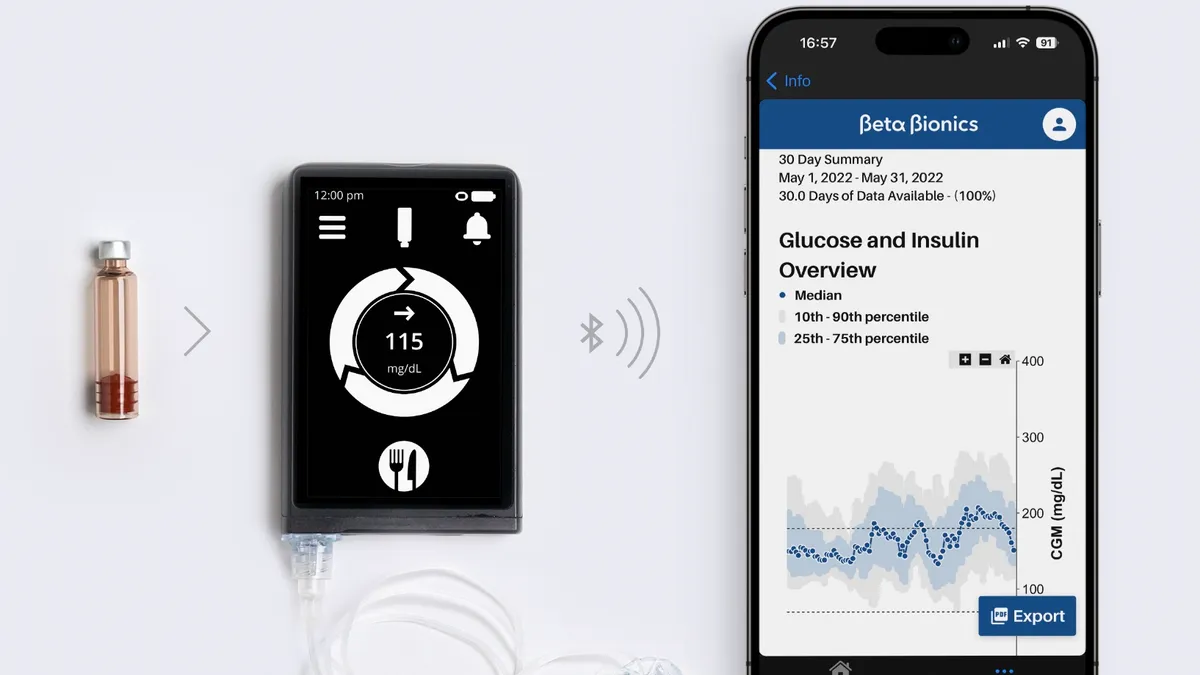

"Medical device data, however, are currently fragmented by device type, ranging from consumer health applications to wearables, ambulance-mounted equipment, and both moveable and stationary devices in clinical settings. This fragmentation underscores the need to facilitate seamless interfacing by providing common language, protocols, principles, and ground rules," the academics wrote.

The authors acknowledge that authorities on both sides of the Atlantic have made some attempts to encourage the interoperability of medical devices. FDA, which finalized guidance on the interoperability of medical devices in 2017, has a Standards and Conformity Assessment Program that, according to the authors, "indirectly supports" the development of consensus standards. Similarly, the European Medical Device Coordination Group has asked standards development organizations to spread medical device standards.

However, the researchers want U.S. authorities to do more to promote the interoperability of medical devices by learning from the work on EHRs. Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) provides a standard for moving data between EHRs but, according to the academics, medical information remains "notoriously balkanized" with the spread of data across home wearable devices, outpatient clinics and hospital care preventing any one clinician from getting a full picture of a patient's condition.

To improve medical device interoperability, the authors envisage the formation of a public-private partnership that brings together standards development organizations such as the Medical Device Innovation Consortium, Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation and the American National Standards Institute. The goal is to gather the "technical and systems expertise" needed to support interoperability.

Such a public-private partnership could build on earlier initiatives. The authors argue against the creation of new, IoT-specific standards, calling instead for the retooling of existing interoperability programs and security standards such as HTTPS, W3C and Web of Things to accommodate the specific functions of medical devices and address cybersecurity concerns.

"This approach from the ground up would avert many of the implementation challenges facing EHR interoperability because it extends far beyond FHIR’s narrow focus on data exchange formats alone. The FDA should encourage the development of an industry-wide medical IoT harmonization initiative, be it within an existing organization or one formed for the task. Furthermore, a new FDA digital health advisory committee could facilitate private sector coordination and gather stakeholder input," the researchers wrote.

The authors list a range of potential positive outcomes of improved device interoperability, using the experience of the consumer technology and telecommunications industries to make their case. Work on interoperability standards in those industries, such as Bluetooth and USB specifications, mean that keyboards, web cameras and headphones function out of the box, without extra software downloads, on almost all computers.

Similarly, every smartphone can connect to every WiFi network, despite the involvement of multiple vendors, and work across different carriers and product generations.

Applied to healthcare, the researchers see interoperable medical devices improving quality, safety and operational efficiency by enabling clinicians to access all relevant information in near real-time. The specific benefits vary across different parts of the healthcare system.

"In the intensive care unit a combination of networked ventilators, pulse oximeters, and telemetry monitors could provide real-time, targeted alerts to a clinician’s smartphone warning of a rapidly deteriorating patient, a task currently requiring a clinician at the bedside, or alternatively combat alarm fatigue to discern meaningful alarms requiring intervention," the authors wrote.

The researchers cite other potential benefits in the treatment of hospitalized heart failure patients. In that context, the use of "networked scales and Foley catheters could automate the manual tasks of tracking weight and urine output." As tracking urine output is an hourly task, there is a significant opportunity to reduce the burdens on healthcare professionals.

The authors also see benefits in clinical research, noting that simplifying data acquisition in community-based trials could lower the cost of device development.