Dive Brief:

- FDA's temporary changes to laboratory-developed test regulation early in the pandemic can provide a blueprint for ongoing regulatory oversight of the field, a study by researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) has found.

- Writing in the Journal of Molecular Diagnostics, the researchers discuss how FDA's response to the crisis showed it can oversee LDTs and gave laboratory directors first-hand experience of the agency's review process.

- The study comes as Congress considers two bills with different visions for the regulation of LDTs. Jochen Lennerz, medical director of the MGH Center for Integrated Diagnostics and one of the study's authors, voiced his support for the Verifying Accurate, Leading-edge IVCT Development (VALID) Act which proposes placing responsibility for oversight of high-risk LDTs in the hands of the FDA.

Dive Insight:

FDA has traditionally provided little oversight of LDTs, freeing labs to develop and use their own tests internally. However, the agency has expressed a desire to change its approach, indicating an intent to actively regulate LDTs in 2010 and following up with draft guidance in 2014. FDA backed away from its push to regulate LDTs in 2016, since then lawmakers have presented competing visions without getting legislation passed.

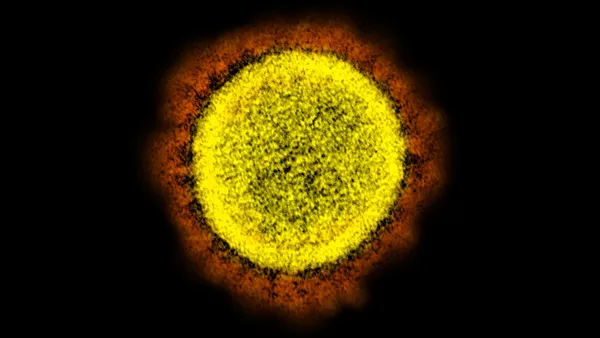

The COVID-19 crisis brought a temporary change of approach. Rather than leave labs free to develop and use tests for SARS-CoV-2, FDA required the submission of LDTs for emergency use authorization. The experience gave a glimpse of how a more actively regulated LDT space might look.

After analyzing the experience, the MGH researchers concluded "the adoption pattern and initial review times provide hard data that FDA oversight of LDTs, albeit temporary, is possible." FDA later allowed LDT use without authorization but asked labs with EUAs to validate the accuracy of their tests against a reference panel in a labeling update study.

"The data of the labeling update study emphasize the value of agency-verified reference materials; this lesson goes beyond inactivated viral reagents and highlights the practical value of these regulatory science tools to establish and assess diagnostic performance metrics," the authors of the paper wrote.

Working with FDA to get tests to market "demystified" the authorization process and gave laboratory directors insights into the regulatory review process, according to the MGH researchers. Notably, the experience showed that "the requested data for both EUA and the labeling update study are the same as any credible laboratory would do as part of their own in-house validation."

Over the months in which FDA exercised greater oversight of LDTs, lawmakers introduced two bills with different visions for the future of the field. Plans for a tiered, risk-based system set out in the VALID Act drew a mixed response, with the American Association for Clinical Chemistry (AACC) arguing it "introduces new and redundant regulatory hurdles" while AdvaMed was more upbeat. Lawmakers reintroduced the VALID Act in June.

The Verified Innovative Testing in American Laboratories Act (VITAL) was introduced shortly after the VALID Act. The second proposal attracted support from organizations critical of VALID, including AACC, for leaving clinical laboratories free from FDA requirements.

As MGH's Lennerz sees it, the COVID-19 experience supports the more hands-on approach set out in the VALID Act. "I think the FDA has the appropriate standing to obtain comprehensive comparison data and help establish tools to regulate complex diagnostic tests," Lennerz said in a statement.