Dive Brief:

- FDA has finalized a guidance document on the humanitarian device exemption (HDE) program that lays out current review practices for applications, post-approval requirements and special considerations under the pathway.

- The guidance also explains the criteria FDA considers in determining whether a company has demonstrated “probable benefit” for marketing authorization for a humanitarian use device (HUD).

- Following issuance of the draft guidance in June 2018, industry group AdvaMed sought clarity on how manufacturers will show probable benefit and pushed back on certain factors the agency proposed looking at to decide if a product is eligible to turn a profit.

Dive Insight:

A humanitarian device exemption is available to manufacturers of devices that diagnose or treat rare diseases or conditions affecting fewer than 8,000 people. A device approved under an HDE application is exempt from the requirement to demonstrate a reasonable assurance of effectiveness.

To use the pathway, device makers must demonstrate that no similar device exists and that there is no other way to bring the device to market.

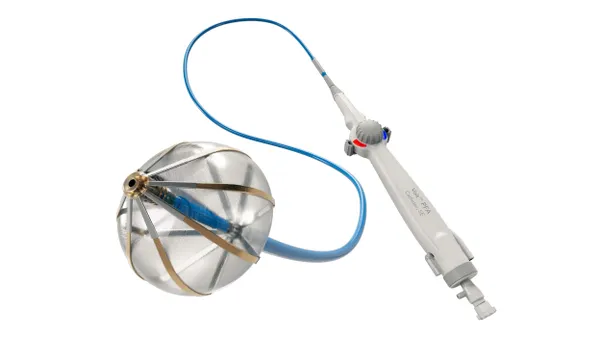

In all, 76 medical devices have been approved through the HDE regulatory pathway, FDA said. They range from a device that allows patients with certain spinal cord injuries to breathe without the aid of a mechanical ventilator to the most recently approved HDE in August for a device to correct idiopathic scoliosis, a sideways curvature of the spine in children and adolescents.

Manufacturers can sell a humanitarian use device for profit if it is meant to diagnose or treat a disease or condition that occurs in children or in a pediatric subpopulation. The FDA guidance prohibits companies from citing economic factors like the cost of conducting clinical investigation as a basis for pediatric development being "impossible" or "highly impracticable."

AdvaMed disagreed with this provision, arguing pediatric populations are geographically dispersed and therefore require many investigational sites which discourages companies from developing devices. But FDA kept language in the final guidance saying that geographic dispersion will only be allowed as justification in "extraordinary circumstances" and "will generally have to be coupled with very small population size."

The trade group was also concerned about FDA’s advice to its staff on how to assess whether a device developer has demonstrated the “probable benefit” of a product. Companies following the HDE process are exempt from the efficacy data requirements of other device pathways but must still show the probable benefits of their products outweigh the risks.

When performing a probable benefit-risk assessment, FDA considers the intended use of the device, target patient population and the size of the population. The assessment also considers available alternative treatments or diagnostics.

Furthermore, FDA evaluates the magnitude of benefits, whether patients are likely to experience one or more benefits and duration of effects. While the draft guidance said regulators would take into account patient perspectives, the final version added the agency will also consider care partner perspectives.

FDA doesn't appear to have significantly lengthened the section with advice on how probable benefit is assessed, but the agency did explain which types of evidence can support approval of an HDE application, including investigations using laboratory animals or human subjects, as well as nonclinical investigations and analytical studies for in vitro diagnostics.

The final guidance includes a filing checklist to clarify the required information for the agency to consider the application ready for substantive review, plus tools to assist application review staff in consistent decision-making.

FDA’s final guidance replaces a document it issued in 2010.