Dive Brief:

- FDA has officially banned electrical stimulation devices used to treat self-injury or aggressive behavior with publication of a final rule Wednesday. The action comes almost six years after convening an advisory committee to weigh the ban and four years after actually proposing it, as pressure mounted from lawmakers in recent months to follow through on ending a "barbaric" practice affecting people with disabilities.

- The agency said the devices "present an unreasonable and substantial risk of illness or injury that cannot be corrected or eliminated by labeling." The rule will take effect 30 days after publication, but FDA is allowing a 180-day transition period for the small group of individuals already exposed to the devices.

- It's only the third time in history the agency has exercised its authority to ban a device. Regulators formerly banned prosthetic hair fibers and powdered medical gloves.

Dive Insight:

While patient safety advocates have called for full-fledged bans on many other medical devices over the years, FDA's decision to exercise that authority rather than take other measures is extremely rare. The agency generally addresses safety concerns with a number of other tools, including changing labeling, adding a boxed warning to a device's packaging or requesting a company initiate a product recall.

Under the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, FDA will only ban a device if regulators find it "presents a substantial deception to patients or users about the benefits of the device, or an unreasonable and substantial risk of illness or injury, which cannot be corrected by a change in the labeling." A ban entails complete prohibition of current and future manufacturing, sales and distribution of a medical device.

The electrical stimulation devices (ESDs) covered in Wednesday's final rule are designed to immediately try to stop self-injurious or aggressive behavior by administering electrical shocks through electrodes placed on the skin. But FDA said evidence shows the devices have been linked to significant physical and psychological risks, including depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, pain, burns and tissue damage. Worse, the population being exposed to the devices may often have difficulty communicating that pain due to intellectual or developmental disabilities.

Definitive action has been a long time coming. In 2014, the agency held a public meeting of its Neurological Devices Panel to weigh a potential ban, which ultimately led to a 2016 proposal to do so. The public comment period that followed drew more than 1,500 responses. FDA said feedback overwhelmingly supported following through with the ban, and the final version of the rule includes only minor, clarifying changes.

"Evidence of the device's effectiveness is weak and evidence supporting the benefit-risk profiles of alternatives is strong," FDA said in a statement Wednesday, citing medications and other behavioral treatments as viable substitutes.

The agency is aware of only one U.S. facility actively using the devices, where no more than 50 individuals are thought to be exposed to the treatment. That device was developed, and is used, at the Judge Rotenberg Educational Center in Canton, Massachusetts, which advocated for its continued use at the 2014 meeting. Still, the ban ensures similar devices cannot be adopted elsewhere in the future.

FDA clarified that the rule does not apply to certain other ESDs, otherwise called aversive conditioning devices, used for indications like smoking cessation. It also said similar FDA-regulated technologies like cranial electrotherapy stimulators and transcranial magnetic stimulation are believed to be safe and effective and fall outside the scope of the rule.

Finalizing the ban was part of FDA's fall 2019 to-do list, with a deadline of December. As 2020 got underway and no final rule was in place, eight high-profile U.S. senators on the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee sent a letter to Commissioner Stephen Hahn on Feb. 10 calling for "immediate action."

"Unfortunately, the FDA missed its deadline, allowing the continued use of electric shock on people with disabilities, including children. This is unacceptable," the senators wrote. "The proposed rule would end a barbaric — and disproven — practice and prevent punishment using electric shock for self-injurious and aggressive behaviors."

FDA ultimately agreed.

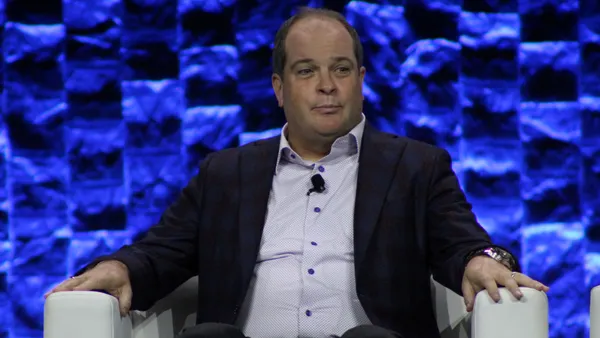

"Since ESDs were first marketed more than 20 years ago, we have gained a better understanding of the danger these devices present to public health," William Maisel, director of the Office of Product Evaluation and Quality in the FDA's Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in an FDA statement Wednesday. "Through advancements in medical science, there are now more treatment options available to reduce or stop self-injurious or aggressive behavior, thus avoiding the substantial risk ESDs present."