With adoption of the Mako robotic surgery platform picking up and Stryker announcing its largest acquisition in company history, 2019 displayed both the old and new fruits of the medtech's dealmaking under CEO Kevin Lobo.

Lobo has overseen more than 50 deals since taking up Stryker's lead role in late 2012, none bigger than the planned acquisition of Wright Medical announced in November.

Stryker's play for Wright Medical, coming with a total price tag of $5.4 billion, may seem out of sync with the company's typical brand of tuck-in M&A, which Lobo said makes it a "serial acquirer.”

"I believe that companies that acquire with a regular cadence — they outperform companies that are not serial acquirers," Lobo said in an interview with MedTech Dive, days before announcing one of the industry's largest acquisitions of the year. "We're a company of singles ... we tend not to be swinging for the fences with big deals."

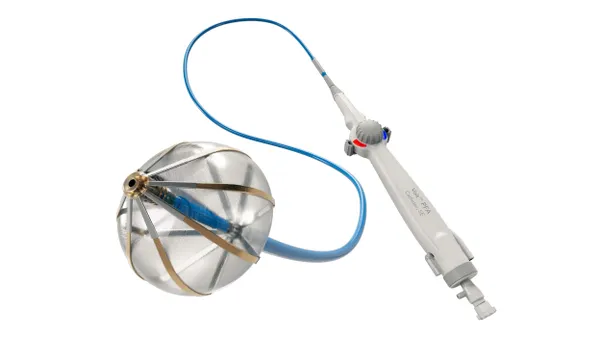

The Wright Medical deal caps a year of relative quiet, despite 9.7% year-to-date growth at Stryker, supported by gains from its line of Mako robots used in joint replacement surgeries. The Kalamazoo, Michigan company grew that technology following a $1.65 billion buyout of Mako Surgical in 2013, less than a year into Lobo's role as chief executive.

Robotics was not initially popular with many investors, he said. "Robotics was not seen as being necessary in orthopaedics by a large percentage of the population," Lobo said.

But entering his eighth year at the helm, Mako appears to be paying off for Lobo. Stryker has sold at least 130 of the robots this year and analysts have said the impact from a Zimmer Biomet robot now competing for knee business has so far been marginal.

Mako is a key example of an acquired technology that's had time to mature under Lobo's watch.

"I think Mako was the really transformational one in terms of Stryker getting on board with robotics before some of their competitors in the space," said Dave Keiser, equity research analyst at Northcoast Research.

Numerous companies in medtech have followed a pattern of finding and taking out fast-growing companies with good technology, he said, but that playbook "seems to be one that’s consistently executed well" at Stryker.

"I can’t think of many [deals] where expectations haven’t been met,” or the end result isn’t better than anticipated, Keiser said.

Lobo shares that confidence. "The more you deals you do, the better you get at it and your integration is better," he said. "You can assess the targets, make sure you pay the right price."

The success of some big deals, like last year's takeover of K2M, has yet to be proven. Executives noted on Stryker's most recent earnings call that sales force integration efforts have taken longer than expected.

But, by and large, since the start of Lobo's tenure in 2012, Stryker has "gone from good to much better" at integrating deals, said Debbie Wang, senior analyst at Morningstar. And Lobo has proven to be good at identifying business additions that would be valued by Stryker’s hospital customers.

"We have not seen the kind of spectacular failures that have littered other parts of medtech," Wang said, citing Johnson & Johnson's integration of Synthes and Boston Scientific's fold-in of Guidant. "I don’t think Stryker’s ever been in that kind of a position.”

And now, Lobo holds an even broader leadership role. In March, industry association AdvaMed appointed Lobo to a two-year term as chairman of its board of directors. Beyond the much talked about medical device tax, Lobo pegged potential ethylene oxide sterilization restrictions and medical device litigation advertisements with unclear funding sources as the biggest threats for the trade group to counter.

"Because Kevin leads a really high-profile medtech company, I think that will give him a platform to be able to advocate," Wang said. "He can say a lot of these things and I think people will really listen to him."

Read more

Read more