Everything from hospital gowns and surgical tools to plastic tubing and implantable devices must be sterilized before a surgery to reduce infection risks. One of the most common sterilization methods for medical equipment is ethylene oxide (EtO), a type of gas that has come under scrutiny from regulators and environmental groups for years because of its cancer-causing effects.

The Environmental Protection Agency is required to finalize new restrictions on EtO next year, following years of controversy and litigation about the safety of the gas. The emissions limits are expected to reduce the risk of cancer for people who work in or live near sterilization facilities, but device companies have also raised concerns that some of the proposed changes could result in shortages of medical equipment, as EtO is used to sterilize tens of billions of devices each year.

Industry group Advamed has said there are currently no viable alternatives to EtO for many medical devices. Regardless, the EPA is moving forward with regulations that it says will lower exposure to workers and community members while maintaining the integrity of the supply chain.

In an email to MedTech Dive, EPA spokesperson Shayla Powell wrote that the agency is working with the Food and Drug Administration to reduce the use of the chemical and to support development of alternative sterilization methods.

The agency said its proposals include many controls that are already being used by some facilities, and it expects all 86 commercial sterilization facilities in the U.S. to be able to meet its requirements.

The discussion around EtO has sparked lawsuits, inter-agency debates and supply chain concerns as the industry awaits new regulations.

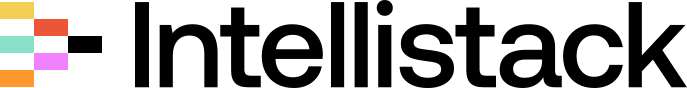

How EtO is used for sterilization

EtO is used to sterilize more than 20 billion medical devices, or about half of all devices, sold in the U.S. each year, according to the FDA. In particular, it’s used for items that might be damaged by heat or humidity, such as devices made of certain types of plastics or resins; devices with multiple layers of packaging; or devices with hard-to-reach places, such as catheters.

It can also penetrate certain types of plastic packaging, making it the main modality for sterilizing pre-packaged surgical kits.

What makes EtO so effective at sterilizing devices also makes it harmful to humans.

“It’s extremely good at breaking down proteins, DNA, RNA,” said Matthew Stiegel, director of the Occupational and Environmental Safety Office at Duke University and Duke University Health System.

The chemical has been linked to increased cancer risks and other health effects when inhaled.

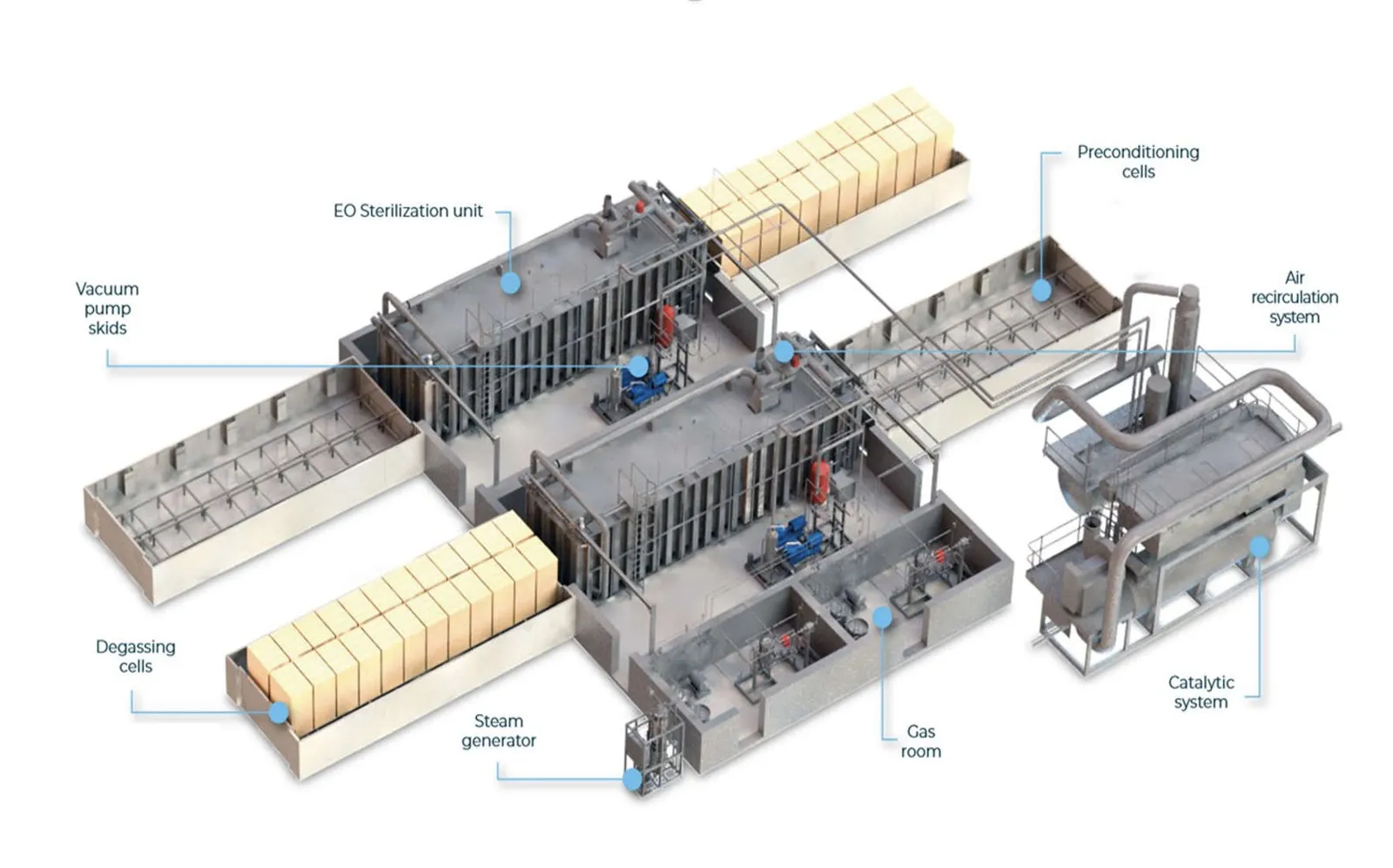

Medtech firms can send their equipment to an outside facility or operate their own plants in-house to sterilize devices before they’re sent to customers. Sterigenics and Steris are two of the largest commercial sterilizers in the U.S., according to an August research note from Keybanc analysts. Medtronic, Becton Dickinson, Baxter and Stryker are among the companies that operate their own sterilization plants.

BD uses sterilizers that are roughly the size of a train car, spokesperson Troy Kirkpatrick said in a phone interview. Devices are manufactured, packaged, boxed and loaded onto pallets, which are then run through the system on a conveyor belt.

“We can put multiple pallets of product into one sterilization cycle,” Kirkpatrick said.

After devices are treated with EtO, the gas is sucked up into an oxidizer that burns it up, and the pallets are aerated in separate, enclosed rooms.

The EPA is expected to finalize its proposal next year

The EPA is looking to address EtO used in sterilization through two different regulations: one that would enforce stricter emissions limits for sterilization facilities, and one that would increase protections for workers and people who live near facilities, and limit how much gas is used in a sterilization cycle.

Currently, there are no emissions restrictions for facilities that use less than one ton of EtO per year. However, the EPA proposed a rule in April that would tighten emissions limits for medical device sterilization facilities under the Clean Air Act, as well as add limits for all sources of emissions, not just for sterilization chamber vents and aeration room vents.

The agency expects the changes would reduce EtO emissions by 19 tons per year, and no individual would be exposed to EtO levels that correspond to a lifetime cancer risk of greater than 1 in 10,000, the upper bound of what the agency considers an acceptable risk.

Currently, an estimated 23 of 86 sterilizers in the U.S. meet all of the proposed requirements, the EPA said in an email. Many other facilities meet at least some of the requirements.

“The standards we have proposed are based on real-world data that we have gathered from facilities and the latest control devices,” EPA spokesperson Powell wrote. “All facilities should be able to meet the proposed requirements.”

The EPA is expected to finalize those standards by March 1, 2024, per a consent decree signed in May by a U.S. district judge. Companies would then have 18 months to implement the required pollution controls.

The EPA also issued a Proposed Interim Registration Review Decision that regulates EtO as a pesticide. The proposal includes specific worker protections, engineering controls and limits on the concentration of EtO used per sterilization cycle. The timeline to finalize the decision is less clear — the EPA told MedTech Dive it expects to publish the next document, an interim or final decision, in 2024.

Medtech companies ask for more time

Advamed, BD and Medtronic have pushed for more time to meet the proposed emissions limits.

One concern is that sterilization facilities would seek the same equipment from a “very limited group of suppliers,” and will need time to design, procure, build, install and validate all of the new systems, BD wrote in comments submitted to the EPA.

“Will every facility be ready? I think the answer to that is no,” Greg Crist, Advamed’s chief advocacy officer, said in an interview.

Crist said there are two major manufacturers of this abatement equipment, Lesni and Anguil Environmental Systems, that make oxidizers and scrubbers.

Will every facility be ready? I think the answer to that is no.

Greg Crist

Advamed’s chief advocacy officer

The changes in the proposed interim decision have proven more controversial. Crist said some of the provisions are “unworkable,” specifically pointing to new limits on the amount of EtO used per sterilization cycle to 500mg/L. Companies would have five years to implement the change for existing cycles and two years for new cycles.

The EPA said in its proposal that facilities use much higher concentrations of EtO than needed for sterility assurance, in some cases using double the necessary concentration.

The FDA, on the other hand, warned that the limit, if implemented, “will present some unique challenges,” agency spokesperson Audra Harrison wrote in an emailed statement, noting that the EPA estimated the average EtO concentration within the chamber during sterilization is 600 mg/L.

Advamed and Medtronic have also said that the EPA is stepping into the FDA’s domain with these limits, as the FDA sets requirements for device sterility.

Some elements of the EPA’s proposed interim decision would supersede earlier rules set by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. In 1984, OSHA set a permissible exposure limit for EtO of 1 part per million, but “scientific evidence has accumulated suggesting that the current limits are not sufficiently protective,” the EPA wrote.

The agency proposed that workers should wear respirators if the concentration of EtO in the air exceeds 10 parts per billion.

“The interesting thing is definitely going to be the interplay between OSHA and EPA, how they figure out a middle ground or an adoption of one way or the other,” Duke’s Stiegel said.

What have companies done to reduce emissions?

Some companies have also begun to install emissions controls in advance of the EPA rule, spurred in part by the anticipated regulatory actions, new technologies and lawsuits.

BD, Sterigenics and Steris “are well-positioned to be compliant” with the new emissions limits given their recent facility enhancements, Keybanc analysts wrote.

For example, BD spent more than $70 million in the last three years targeting residual emissions, referring to EtO left on the packages after they’ve been sterilized. The company installed dry bed systems at its U.S. facilities to absorb remaining EtO that may be released while devices are stored in warehouses, Kirkpatrick said.

BD has come under scrutiny for its sterilization practices in the past. Georgia’s Environmental Protection Division ordered the company to pause sterilization at its Covington facility in 2019 after the facility experienced an eight-day valve leak that released more than 54 pounds of EtO into the air. The regulator also issued a notice of violation after finding a warehouse where the company stored sterilized products had estimated EtO emissions of about 5,600 pounds per year.

Meanwhile, Baxter invested more than $46 million in an abatement system from Lesni to control EtO emissions from its Mountain Home facility in north Arkansas, according to comments submitted to the EPA. In 2020, the facility reported the third-highest emissions of the chemical in the U.S., according to the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.

Steris and Sotera Health, the parent company of Sterigenics, have spent more than $30 million each on equipment upgrades in the past two to three years in anticipation of tighter regulations, analysts at Moody’s Investor Services wrote in June. They expect the total cost for all companies to be “significantly higher” than the EPA’s estimates.

David Fusco, a partner at law firm K&L Gates, said states have also been following the EPA’s lead. Multiple lawsuits were filed against Sterigenics, Steris and BD following the agency’s risk assessment. In January, Sterigenics reached a $408 million settlement with hundreds of claimants in Illinois.

“Even though much of the publicity has been surrounding Sterigenics and a few specific sterilizers, I think any company that has ethylene oxide emissions or uses ethylene oxide in its business should be mindful of these developments, paying close attention to the regulations, consulting with counsel to make sure they understand if they have any risk of potential litigation, and also make sure that they're compliant with what might be coming down the pike by the way of new regulations,” Fusco said. “There's a lot happening quickly, and it's hard to keep track of it all sometimes.”

Major regulatory actions related to EtO

-

December 2016The EPA publishes its final Evaluation of the Inhalation Carcinogenicity of Ethylene Oxide, characterizing the chemical as carcinogenic to humans.

-

Dec. 27, 2021The agency requires 29 facilities, including those managed by Boston Scientific and Sterigenics, to track their EtO emissions and processing.

-

Aug. 3, 2022The EPA releases a list of sterilization facilities that contributed to elevated cancer risk for the surrounding communities. The list includes facilities run by BD, Edwards Lifesciences and Medtronic, although the agency has since cautioned that the information may no longer be current as companies have made updates to facilities.

-

April 11, 2023The EPA issues a proposed air toxics rule that would set new emissions limits for commercial sterilizers that use EtO. It also issues a proposed interim decision to mitigate human health risks, regulating EtO as a pesticide.

-

Jan. 9, 2023Sterigenics agrees to pay $408 million to settle more than 870 lawsuits with plaintiffs who said they were exposed to EtO emissions from its former facility in Willowbrook, Illinois.

-

August 23, 2023A U.S. district judge signs a consent decree requiring the EPA to adopt a final rule on commercial sterilization standards by March 1, 2024.

How the regulations would reduce cancer risks

At the heart of the EPA’s actions are the health risks that have been associated with EtO.

“We know that ethylene oxide exposures can increase the risk of cancer,” said Tracey Woodruff, director of the University of California San Francisco’s program on reproductive health and the environment.

In 2016, the EPA determined the chemical is carcinogenic, based on an analysis from its Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS). The agency found increased cancer risks for people living near a sterilization facility over 70 years, and for workers handling the chemical in a facility over 35 years. Studies showing EtO’s DNA-damaging properties date back as early as 1940, according to the agency’s report.

People in these communities have been exposed to cancer-causing ethylene oxide for decades. So it seems like the industry should do more to make it so that they can have sterile equipment while also keeping those communities healthy.

Tracey Woodruff

Director of the University of California San Francisco’s program on reproductive health and the environment

The chemical has also been linked to other health risks that aren’t covered by the EPA’s assessment, which focused on cancer, Woodruff said.

EtO has been linked to reproductive problems and neurological effects. Peripheral neuropathy, impaired hand-eye coordination and memory loss have been reported in workers exposed to the chemical for longer periods, the EPA said.

The EPA’s report also raises health equity concerns. Roughly a third of the 19.4 million people who live near a sterilization facility are Hispanic or Latino, and a disproportionate number of people who live near the highest-risk facilities are African American.

The agency estimated that 18,000 people are currently exposed to EtO with a cancer risk of 1 in 10,000, exceeding the EPA’s limit for acceptable health risks. If the agency's emissions limits are implemented, that number would fall to zero.

“People in these communities have been exposed to cancer-causing ethylene oxide for decades. So it seems like the industry should do more to make it so that they can have sterile equipment while also keeping those communities healthy,” Woodruff said.

How the FDA is working with the EPA

The FDA’s actions are a focus for medical device companies, which need to meet the agency’s standards to ensure products are sterilized and must notify the FDA if they change how an approved device is sterilized.

The FDA has spoken up about its concerns about potential device shortages.

“If implemented as proposed, the FDA is concerned about the rule’s effects on the availability of medical devices,” Harrison wrote. “Our supply chain program is ready to work with industry to help prevent and mitigate potential shortages due to reduced supply of certain EtO-sterilized medical devices as industry works to meet EPA’s final requirements.”

The FDA also has an active role in looking for new solutions. For example, in 2019, the agency launched two innovation challenges to identify new sterilization methods and reduce EtO emissions. It has also developed master file pilot programs to make it easier for companies to change to other sterilization methods. Some other modalities that currently exist include steam, radiation and hydrogen peroxide.

“While signs of innovation are promising, other methods of sterilization cannot currently replace the use of EtO for many devices due to compatibility challenges and a lack of sterilization capacity,” Harrison wrote.

The EPA told MedTech Dive it is working with other agencies, including the FDA, on potential supply chain issues and will use input from public comments to make any final decision.

“Our goals remain reducing the exposure to EtO while maintaining the integrity of the medical device sterilization supply chain,” the EPA’s Powell wrote.