Aloha McBride, EY Global Health Leader

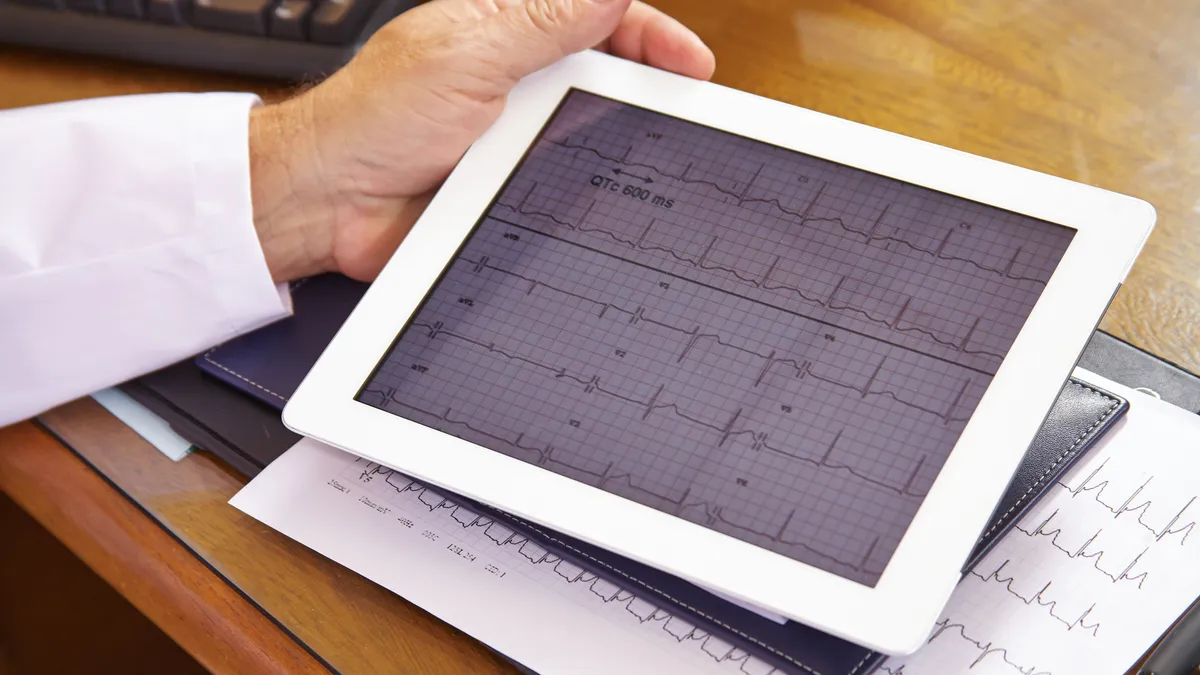

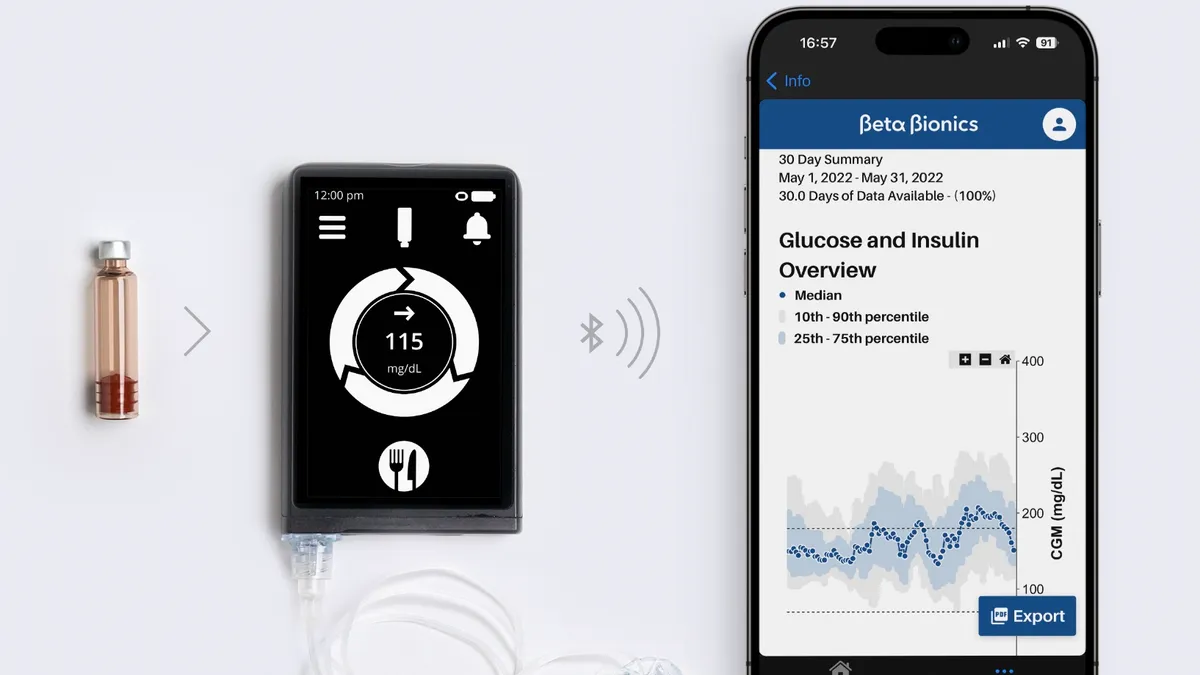

Emerging digital health technologies that double in function as a medical device now fall under the banner of digital therapeutics (DTx).

As software that functions as a medical device in its own right (SaMD), these are clinical grade therapeutics that hold great promise for cutting through and motivating people to achieve their healthcare goals. What sets DTx apart is the adaptability to cross both time and geographic boundaries to bring evidence-based care to people anywhere, at any time.

Sensors, wearables and artificial intelligence (AI) allow for remote monitoring and supportive behavior change in specific clinical conditions. Individuals receive timely, data-driven precise and personalized health insights. Bringing these insights together may also enable capabilities to address health issues at the population level.

A key defining feature of DTx is the use of software programs and advanced technology in the diagnosis and treatment of complex and chronic health conditions. It is worth noting the distinction between digital health, digital medicine and digital therapeutics drawn by the Digital Therapeutics Alliance, a trade group made up of established players from Bayer and Roche to startups like Happify Health.

Digital therapeutics are seen as a subset of digital health and are products that "employ high quality software to deliver evidence-based therapeutic interventions that prevent, manage, or treat a broad spectrum of physical, mental and behavioral conditions."

This critically discerns between consumer health and well-being products and clinical-grade technology-based products that track and monitor a patient to provide support based upon behavioral science, cognitive behavioral therapy and motivational strategies. This is an important distinction because I wonder how a consumer, or perhaps even clinicians for that matter, can distinguish between the vast numbers of health, fitness and clinical-grade apps. Do we have sufficient knowledge to make an informed or reasonable judgment regarding the clinical benefits, scientific validity or even if an app may cause direct harm? And can this knowledge keep pace with such rapidly evolving technologies?

It is the software, data collection and data use of elements of DTx that raise a cautionary note. We look to regulators to determine risk through approvals processes and standards. But the very nature of software that collects personal data means that it is important to ensure the safety, privacy and security of that data. Both consumer and clinical grade apps and technologies collect a lot of data, but it is unclear whether consumers are given sufficient information to make an informed choice regarding the sharing of their data.

A recent analysis of the privacy practices of medical and health and fitness apps published in BMJ found that two-thirds of the over 20,000 apps studied had at least one third-party service (such as an analytics service, advertisement library or social media provider) embedded in them. A majority (88%) of apps studied could access and potentially share personal data. More health and fitness apps lacked a privacy policy (36%) compared with medical apps (17%).

The authors note concerns around lack of transparency of data privacy, lack of enforcement of privacy standards and the conflict between privacy principles and business models built around sharing of user data or selling subscription services. Individuals can be identified from anonymized data, and a key challenge remains for the health industry to get the right balance between privacy and data ownership rights and commercial considerations.

Demand is growing for technologies that use AI and machine learning in healthcare, especially as apps become embedded in care pathways. Algorithms, however, are data-hungry and their value is dependent upon the quality and robustness of the data used to train them. Algorithmic bias is a noted issue and in a recent publication of the Algorithmic Bias Playbook, researchers at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business detail how pervasive algorithmic bias, often on racial and economic details, can influence clinical care, workflow and health policy.

Privacy regulations governing the collection and secondary use of personal data make it difficult to gather sufficient real-world data to train algorithms. Clinical data gathered through electronic health records and smartphone apps is an important source of information on the treatment of health conditions and patient outcomes in everyday settings. However, this data is often locked in siloed systems and can be expensive and slow to collect and analyze. The data itself can be messy, patchy and insufficiently robust.

Synthetic data has been held out as holding great promise for replicating and augmenting observational data with generated data that mimics and simulates real-world data. However, whether this can effectively mitigate the bias of algorithms is up for debate. Synthetic data is still only as robust as the data going into its creation – biased input data sets will still remain biased. Synthetic data can be used to model clinical conditions and user phenotypes without revealing patient data and this can have significant application in areas of data paucity including rare diseases and chronic condition trajectories over a lifetime.

However, the emergence in the public and celebrity domains of deepfakes – the creation of synthetic or fake images using pictures, video and audio (usually of a celebrity or politician) through deep learning technology, should raise a red flag to the health industry.

As virtual care and remote patient monitoring as well as DTx become a core part of healthcare and a person's details are captured using multi-modalities, what must the industry have in place to protect personal health information and to prevent the use of personal information or identity for fraudulent or malicious purposes?

More questions than answers exist right now. A stream of new therapies are coming into the market that hold great promise for supporting behavior change and treating chronic conditions. These apps and products are sources of information and decision support for both consumers and clinicians, especially as care models move to anywhere and anytime. This information influences decisions that impact people’s lives and thus we have to be reassured that it is trustworthy and of a high quality. The continued evolution of AI and machine learning offers great promise, but also concerns.

As these technologies come onstream, there is an urgency to resolving the many issues around regulation, classification, safety and quality monitoring as well as protection of private personal information. Privacy requirements must be met with full transparency by all in the value chain. Algorithms need to be regularly audited and screened for bias and discrepancies eliminated and clinicians play a vital role in explaining the key features of apps and privacy risks to patients.

These applications have come a long way – they bring great promise but potentially raise some risk. How best can we bring it all together in this new era of medical technologies?

The views reflected in this article are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the global EY organization or its member firms.