This story is part of a MedTech Dive series examining the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the medtech industry, published six months after the U.S. declared a public health emergency. You can find the other stories here.

When the U.S. declared a public health emergency on the final day of January in response to the coronavirus pandemic, it was clear the nation lacked the diagnostic capabilities to combat the rapidly spreading infection.

Six months later, COVID-19 cases are surging in the South and West. But despite new tests coming online from companies such as Abbott, BD, Roche and Thermo Fisher and a capacity ramp-up by commercial labs like LabCorp and Quest, the nation is still only able to muster 4.5 million tests per week.

That’s a far cry from the 30 million tests weekly needed within the next three months to safely reopen communities and state economies, and keep them open, according to the Rockefeller Foundation, which this month proposed a National COVID-19 Testing & Tracing Action Plan to address the shortfall.

Echoing many other public health experts, the plan’s authors warn the U.S. is losing its battle against COVID-19 and that testing is the only way to avert further devastation until a vaccine or effective therapeutics are widely available.

The Rockefeller authors contend that within the next three months to contain the pandemic, what's required is access to diagnostic testing for Americans with symptoms — at least 5 million tests per week with turnaround times of less than 48 hours — as well as 25 million fast, inexpensive screening tests for asymptomatic people.

The national focus should not just be on bringing more COVID-19 diagnostic tests to the market, but significantly boosting onsite and home testing of people not showing symptoms, the foundation contends.

Abbott Labs, whose point-of-care ID Now platform was one of the first molecular tests to get an FDA emergency use OK, is also betting that large scale rapid testing is the next chapter of the pandemic response.

“With the phased easing of shelter-in-place restrictions, we’re entering a new phase where continued testing of symptomatic patients will start to overlap with broader surveillance testing of asymptomatic patients in order to better track, understand and contain the spread of the virus until we have broad vaccine availability,” Abbott CEO Robert Ford told investors on a July 16 second-quarter earnings call.

While the FDA has cleared more than 150 molecular tests, only two antigen tests, sold by BD and Quidel, have emergency use authorization. Abbott is now working on its own antigen test.

Unlike polymerase chain reaction tests, which detect viral genetic material, antigen testing is designed to determine if a sample contains proteins found on the surface of the coronavirus, enabling delivery of results in minutes rather than days.

Some public health experts are advocating a broad push using the antigen tests, especially as LabCorp and Quest struggle to keep up with increased demand for molecular diagnostics as U.S. coronavirus cases rise.

From slow and accurate to fast and good enough

Whereas molecular tests are typically highly accurate and usually do not need to be repeated, FDA has recommended that negative results from antigen tests should be confirmed with a molecular test. In particular, the agency has warned that antigen tests are not able to definitively rule out active COVID-19 infection.

"That’s why when the FDA approved those assays, they approved it under the remark that if it’s negative you have to reconfirm it with a PCR assay. And obviously most are negative, so you have to do a lot of PCR assays following that," Roche Diagnostics CEO Thomas Schinecker told investors on a Thursday earnings call.

However, Mara Aspinall, a biomedical diagnostics professor at Arizona State University’s College of Health Solutions, makes the case that the U.S. cannot break the chain of transmission if the coronavirus outpaces public health efforts.

What’s needed is a “paradigm shift from exquisitely accurate-but-slow tests to fast-and-good enough to quarantine," she said. “Slow and accurate works for clinical management, but this virus is a sprinter not a marathoner. We need fast and frequent tests just to keep up."

That approach has been endorsed by top U.S. health officials, including National Institutes of Health Director Francis Collins and federal testing czar Brett Giroir.

Earlier this month, FDA granted emergency use authorization to BD’s rapid, point-of-care coronavirus antigen test, making it only the second such diagnostic to receive a nod from the regulatory agency.

A Quidel product, which claimed the antigen category's first EUA in May, delivers results in 15 minutes. BD's test, which runs on the company's widely used Veritor Plus System, also delivers results in 15 minutes.

What appears to set Quidel's antigen-based diagnostic apart from BD's is its accuracy. Quidel on July 17 shared new data showing its COVID-19 antigen test has 96.7% sensitivity which is comparable to the sensitivity rates of PCR tests, according to the company.

"Lower sensitivity had been an argument we have heard over and over about why antigen testing was not going to be used and this should help put that to bed," William Blair analysts wrote in a July 20 note to investors.

The analysts contend Quidel's latest data on its antigen test puts it "on par with many of the molecular tests on the market" as well as "above the performance of the other antigen test on the market from BD."

By comparison, BD's antigen test has 84% sensitivity. Asked if BD is looking to update its clinical performance data, a spokesperson told MedTech Dive they are not aware of any plans to do so.

As for Abbott, CEO Ford declined during the July 16 earnings call to provide specifics in terms of timing and when the diagnostic might be available. He did say antigen tests offer an interesting value proposition compared to molecular testing. Ford emphasized that Abbott’s goal is to produce a reliable antigen test that’s easy to use and, equally important, is affordable.

“I think that’s the critical aspect here. If we want to get to more mass screening, more mass volume, these tests need to be more affordable, and one of the ways you do that is you remove the restriction on the [lab-based] instrument, or requiring an instrument,” he told investors.

When it comes to diagnostic testing, “easy, fast, and cheap” is also what the Rockefeller Foundation is advocating to bring tests to the U.S. market at a national scale needed to effectively respond to the pandemic. The organization envisions point-of-care antigen tests costing $5 to $10 per test, with same-day test results for schools and workplaces, and even faster turnaround times for mobile testing in communities.

“Today the country conducts almost zero such [screening] tests, and we need at least 25 million per week for schools, health facilities, and essential workers to function safely,” wrote Rajiv Shah, president of the Rockefeller Foundation, in the organization’s proposed national testing plan.

The U.S. will need at least another $75 billion in federal funding for testing to reach the plan’s goal of 30 million tests per week by October, including at least 25 million fast, inexpensive antigen tests for asymptomatic Americans, according to the Rockefeller Foundation.

The call for more money for testing comes as a debate continues on Capitol Hill over what the next coronavirus relief bill should appropriate. The HEROES Act passed by House Democrats in May provides an additional $75 billion for testing but Senate Republicans are likely to come up with their own legislation with less funding.

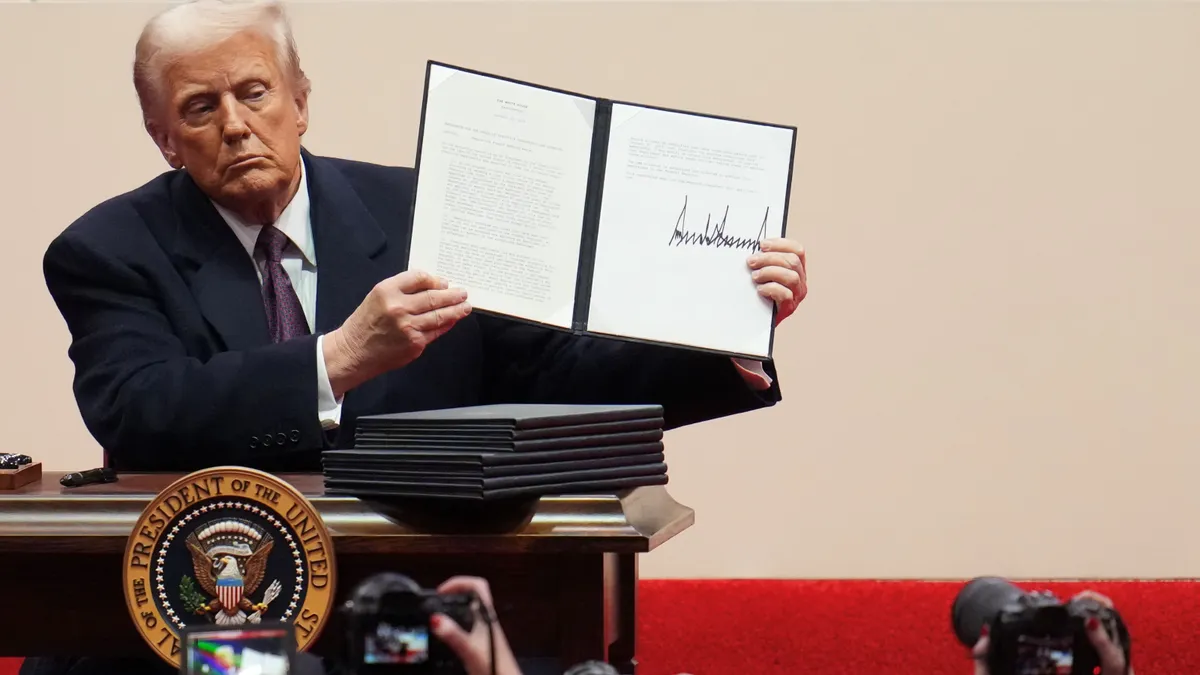

Senate Republicans are considering much lower figures for testing as President Donald Trump has resisted more testing on a false claim that it leads to more cases.

The Rockefeller Foundation also wants the administration to invoke the Defense Production Act, or similar federal program, to jumpstart producing and distributing mass quantities of fast, low-cost antigen tests. The administration reluctantly used the Korean War-era law earlier in the pandemic to force industry's hand in producing ventilators.

LabCorp, Quest struggle to keep up

Fueled by soaring demand for molecular diagnostic testing across the country, particularly in the South, Southwest and West, current test processing delays experienced by the two largest commercial labs are hamstringing America’s COVID-19 response.

Quest reported July 20 that non-priority patients face average wait times for their test results of seven or more days, while "priority 1" patients, or those considered critical, are now having to wait an average of more than two days for results. A company spokesperson told MedTech Dive the company is "planning to issue updated numbers" on Monday afternoon. "Otherwise, the July numbers are the most up to date," she said.

By comparison, LabCorp reported Sunday its average wait time for results was two to three days from specimen pickup, down from three to five days last week, and that turnaround times are "faster" for hospitalized patients.

Nonetheless, slower than 48-hour turnaround times for test results are making contact tracing ineffective. In fact, a study published on July 16 in The Lancet found that test results need to be delivered within a day of a person developing symptoms for contact tracing to be effective in reducing transmission of the coronavirus.

As LabCorp and Quest are having a hard time meeting hotspot-driven demand in a timely fashion, the Trump administration is hoping rapid point-of-care tests from Abbott, BD and Quidel can alleviate the pressure.

Giroir, lead for federal COVID-19 testing efforts, has touted the ability of antigen-based tests from BD and Quidel, as well as Abbott's ID Now molecular test, to be performed outside of lab settings in minutes rather than days.

The testing czar acknowledged Sunday that test results are taking too long. "The delays that most people talk about are at the large commercial labs that perform about half the testing in the country," Giroir said on CNN’s State of the Union, while estimating that the average turnaround is about 4.27 days. "I would be happy with point-of-care testing everywhere. We are not there yet," he added.

NIH director Collins has echoed those sentiments, commenting that wait times for test results are "too long" currently and rapid antigen-based diagnostics could be the answer.

Writing in a New England Journal of Medicine article published Wednesday, Collins and his co-authors noted that while PCR tests are highly sensitive they require a large amount of lab space, complex equipment, regulatory approvals for lab operations, as well as skilled technicians to run them. In addition, they said with this type of testing there is the need to transport specimens to a central lab that leads to further delays.

"For this reason, low-complexity molecular diagnostic point-of-care tests with rapid turnaround have substantial practical advantages," wrote Collins and others, who pointed out that antigen testing can provide quick results "similar to the way pregnancy tests operate." They noted that a number of manufacturers are currently developing them.

A Quest spokesperson told MedTech Dive that "there remains value in molecular diagnostic testing." At the same time, they said the company is "exploring the option to launch its own antigen test" but declined to disclose any additional details. LabCorp currently has no plans for antigen testing, according to a company spokesperson.

Quest's future plans for an antigen test aside, the company is taking other approaches to molecular testing in an attempt to maximize capacity. On July 18 it announced its PCR test, which first got emergency use authorization by FDA in March, was granted an agency EUA for sample pooling, a method meant to screen more people using fewer testing resources.

LabCorp announced Saturday that it also received an EUA from FDA authorizing diagnostic testing of groups of individuals for active COVID-19 infections using pooled testing.

Sample pooling, in the case of Quest's molecular test, allows specimens collected from four individuals to be tested in a pool or “batch” using one test, rather than running each in its own test. LabCorp's pooled testing method involves testing up to five samples at once.

Quest acknowledges the inherent limitation of sample pooling: it's only an efficient way to evaluate patients in regions or populations with low rates of disease. Quest Chief Medical Officer Jay Wohlgemuth said in a statement that while sample pooling will help expand testing capacity it is not a "magic bullet" and "testing times will continue to be strained as long as soaring COVID-19 test demand outpaces capacity."

While LabCorp believes pooled testing can increase its overall testing capacity, the company concedes that specimens with low viral loads may not be detected in sample pools due to decreased sensitivity and that the method may be used for populations at low risk, when testing demand exceeds capacity, or when reagents are in short supply.

However, the Rockefeller Foundation argues that despite testing advancements such as sample pooling, the commercial labs “cannot come close to fulfilling the nation’s screening test needs.”

Lab tests “aren’t convenient, simple, or inexpensive enough to use at the scale needed,” the report says, calling for a ramp-up in antigen testing in schools, offices and beyond.

The Rockefeller Foundation also believes it is critical for the U.S. to look beyond commercial laboratories such as LabCorp and Quest that are overwhelmed and tap the testing resources of other underutilized labs, recruiting academic and other labs.

However, time is of the essence, according to Shah. "We will soon enter a new cold and flu season with potentially 100 million cases of flu-like symptoms that stand to overwhelm our current testing capacity."