Dive Brief:

-

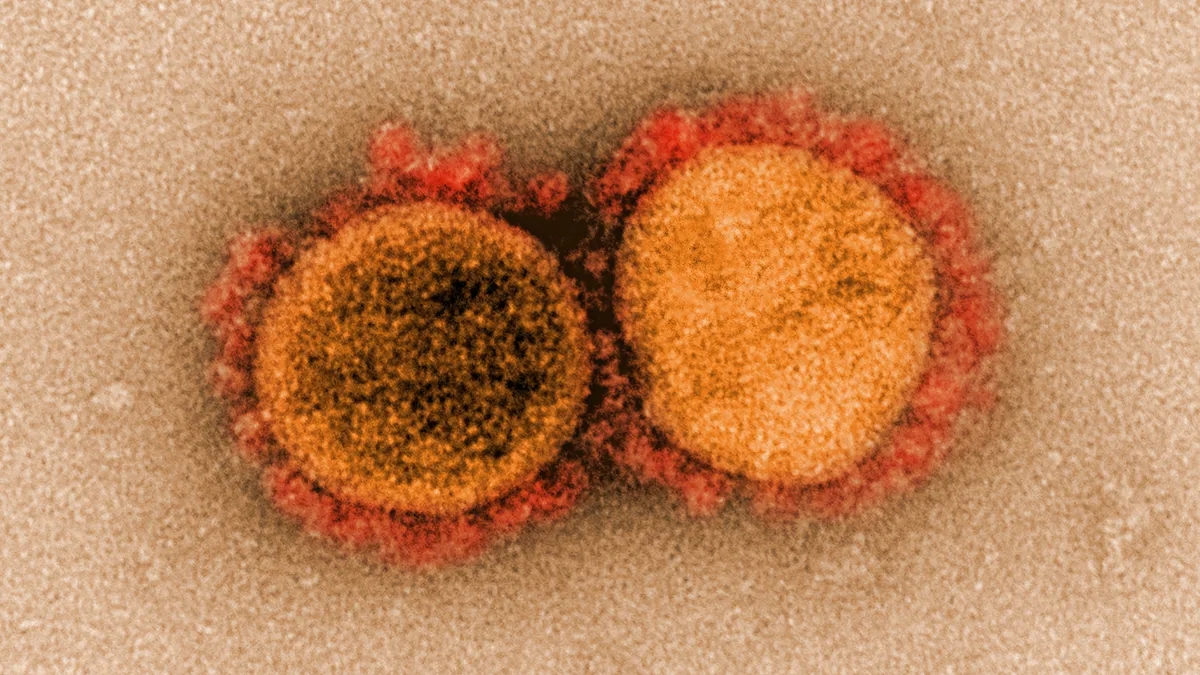

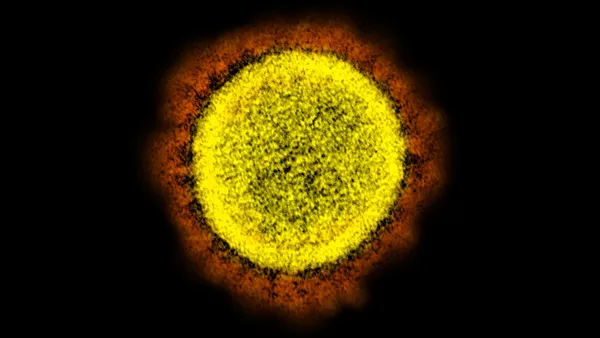

Two small studies have generated mixed evidence of the accuracy of saliva tests for COVID-19 in comparison to more established swab-based methods.

-

In a letter to the New England Journal of Medicine published Friday, Yale University researchers presented results from 70 patients linking saliva tests to the detection of SARS-CoV-2 cases missed by swab-based methods. The researchers found more SARS-CoV-2 RNA copies in saliva samples. Yale's School of Public Health is among a handful of labs with FDA emergency use authorization for a saliva test.

- A separate study published the same day in the Annals of Internal Medicine of nearly 2,000 pairs of samples of those getting both types of tests found less than half of people tested positive in both swab and saliva samples. Almost one-third of people tested positive on their swab test but negative in the saliva sample.

Dive Insight:

A meta-analysis conducted by researchers in Hungary and published this month of early assessments of swab and saliva tests for COVID-19 found little distinction between the two approaches in terms of sensitivity. Swab tests performed better numerically but the difference fell short of statistical significance, leading the researchers to conclude the outcomes of the two approaches “are not very different.”

A Rutgers University lab had the only saliva test with emergency use authorization at the time of that meta-analysis, which looked at studies published before April 25. Since then, multiple organizations have received FDA EUAs for saliva tests, including Fluidigm, Phosphorus and the Yale School of Public Health. Yale received its EUA after showing its kit concurred with a PCR test more than 90% of the time.

The NEJM letter may further the case for saliva testing. Saliva testing detected higher levels of viral RNA and diagnosed 10 percentage points more positive cases than swabs in samples taken in the five days after diagnosis. The data led the researchers to argue “saliva specimens and nasopharyngeal swab specimens have at least similar sensitivity in the detection of SARS-CoV-2 during the course of hospitalization.”

Yale researchers generated further evidence of the value of saliva testing by screening almost 500 asymptomatic healthcare workers. Saliva tests detected SARS-CoV-2 in 13 samples taken from people who were asymptomatic at the time. Matched swabs were available for nine of the people. Two of the swabs generated positive results for the virus.

“Variation in nasopharyngeal sampling may be an explanation for false negative results,” the Yale researchers wrote. “Collection of saliva samples by patients themselves negates the need for direct interaction between health care workers and patients. This interaction is a source of major testing bottlenecks and presents a risk of nosocomial infection.”

The authors of the Annals paper cite some of the same advantages in their discussion of the value of saliva testing.

However, that study of asymptomatic or patients with mild symptoms found evidence that saliva testing may miss positive cases picked up by swab-based methods.

The result may reflect genuine differences between the accuracy of the approaches, or confounding factors such as PCR false positives and the use of different laboratories to process the swab and saliva samples.

Larger assessments that control for such confounding variables may be needed to more conclusively compare saliva and swab tests. In the absence of such assessments, the authors of the Annals paper see enough evidence to suggest that saliva testing is feasible and “may be of particular benefit for remote, vulnerable, or challenging populations."