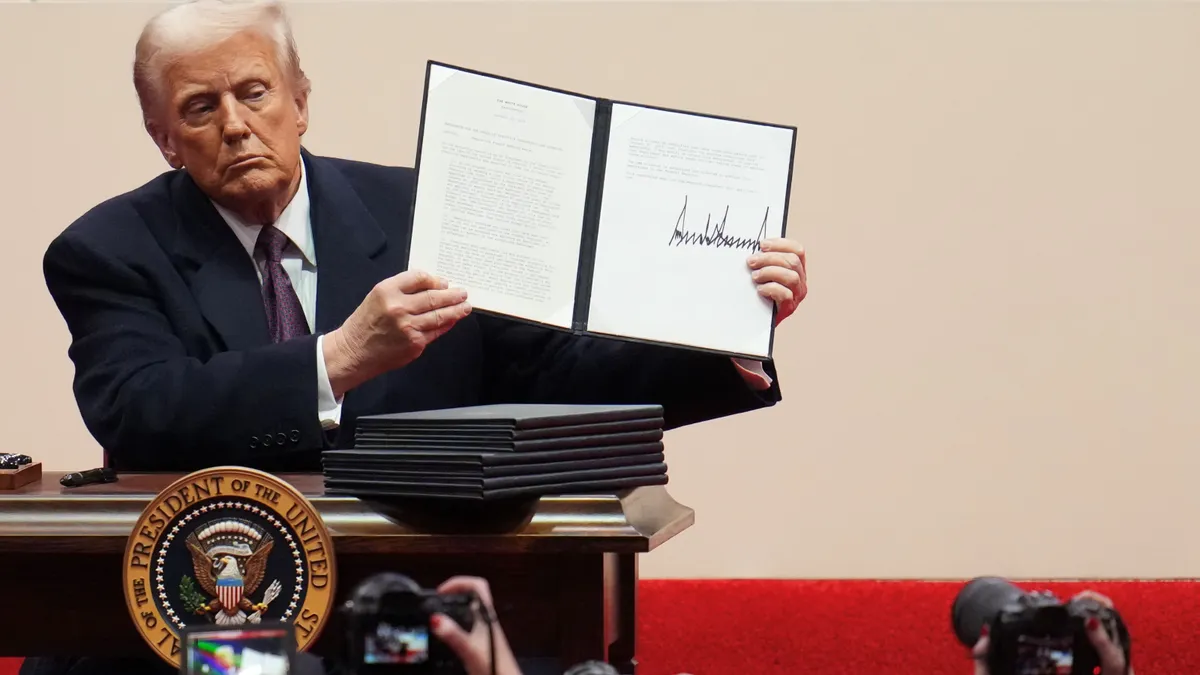

COVID-19 case numbers are once again rising as the BA.5 variant has become dominant across the U.S. The numbers have ticked up past 123,000 cases per day, and new hospitalizations have passed 5,700 per day, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

At the same time, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing is declining, giving public health agencies less visibility into the pandemic.

Ian Lipkin, a physician and the director of the Center for Infection and Immunity at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, talked to MedTech Dive about what’s next for the pandemic and COVID-19 testing.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

MEDTECH DIVE: We have a new variant, some mitigation measures have been lifted and some people just want the pandemic to be over. Where are we now?

IAN LIPKIN: The first point, of course, is that this pandemic isn't over. It's continuing to evolve. We're trying to find a way in which we can respond to it in a rapid fashion and learn to live with it because not only is it well-distributed in humans, but there's a potential now that it's in animals as well, which will make it more difficult to eradicate.

And the two most recent variants, BA.5 and BA.4, are causing infections in people who are fully vaccinated and otherwise healthy. Whether or not these are going to result in a big increase in hospitalizations and serious disease, it's still early to tell. We haven't seen a dramatic increase in hospitalizations like we've seen with the early waves with other variants, but it's still early and this is something that we're all tracking. We also don't know whether or not we're going to see more examples of individuals with the post-COVID sequelae [long-term symptoms that persist after the initial illness].

Looking at COVID testing, do we have the infrastructure to track all of these cases?

LIPKIN: More recently, people shifted to using the antigen test. The problem with the shift away from the PCR test to the antigen test, is that with a PCR test, we would get records of whether or not levels of infection were going up or down in the community. And we have the ability to try to recover the sequence so we can actually track how the virus was changing.

When people shifted to the antigen tests, we started losing the surveillance aspect. So we really didn't know if people were taking a test at home, and when they tested positive whether that test would even register unless those individuals had contacted their local health departments — and most of the time they probably didn't.

The other issue is that people who take these antigen tests may develop a false sense of security if they get a negative response. Particularly with the BA.5 variant that’s circulating [at] present, there can be this eclipse period, where you don't see evidence of infection with the antigen test on people that have infection.

So this has become a huge problem and we're beginning to think about whether or not we need to go back to a different testing regimen. Given that it's possible for us to get testing done with pools of specimens at very, very low cost using robots, we should not be abandoning [PCR] testing.

What’s your recommendation for day-to-day: Should people use more antigen tests? Should they switch back to PCR tests?

LIPKIN: I don't think that there's a standard answer. That's part of the problem. There are people who will tell you that without a positive antigen test, you're not infectious. And I don’t agree. I really think the molecular tests are more reliable.

The other thing is that as people become more tired of testing in general, we are seeing [that] what I would consider common-sense efforts to maintain your safety are lost as well. I've been on planes recently where I and maybe 5% of the people on the plane are wearing masks. Same thing is true on buses and trains and so on.

I'm sure this varies depending on where people live, but are there fewer places where you can go to get a PCR test than before?

LIPKIN: Access is becoming challenging. At Columbia, we were routinely testing a random sample of our population on a weekly basis, so every day there'd be a random sample brought in to test and it allowed us to get some sense as to where we were. We're no longer doing that. What people are doing to look at population level risk is that they're examining sewage, because this gives you a sense of what's circulating within the community and it allows you to track the appearance of different variants.

Some companies have started building multiplex tests for COVID-19, flu and RSV, for example. What are your thoughts on those?

LIPKIN: I think there's an advantage to those tests [in] that you can have much more confidence in a negative result for COVID. If you get a positive result for flu, it's unlikely that people [will] have both infections simultaneously. So there is an advantage to pursuing work with tests like that.

On the other hand, every time you multiplex, you lose some sensitivity.

So far, Congress has not appropriated more funds for COVID testing. What are your thoughts on making sure we have enough resources?

LIPKIN: We're talking about so many things that we've got on the docket right now. We're looking at gun violence and Ukraine and the Jan. 6 hearings. I don't know how much appetite people have for investing in testing, but I think they should. There's no substitute for it. It's one of the best policies that we have for ensuring against us slipping back into the problems of 2020.