Healthcare providers and industry groups are warning Congress of an urgent need to improve standards and practices to protect medical devices and electronic health records from cyberattacks.

Suggestions ranging from better coordination between organizations to federal help in covering the costs of protecting patient data are spelled out in nearly 300 pages of comments submitted to the House Energy and Commerce Committee. The panel in April issued a request for information on how to improve cybersecurity in the medical device sector. Congress is concerned that older “legacy” technologies may be more vulnerable to security threats than their modern counterparts.

The effort is part of a response to the 2017 global ransomware attack dubbed WannaCry that underscored the cybersecurity risks facing device makers, hospitals and healthcare facilities. The massive cyberattack froze computers at hospitals across the United Kingdom and disrupted businesses in more than 100 countries. Hundreds of thousands of devices were infected, according to the House committee.

Cybersecurity issues continue to hound healthcare organizations. The American Medical Association said 83 percent of physician practices report they have experienced some form of a cybersecurity attack, and the majority of doctors are concerned about future cyber attacks on their practices.

“The healthcare sector exchanges health information electronically more than ever before, putting the entire healthcare ecosystem at risk,” the AMA said in comments to the committee.

The AMA urged adoption of public policy that emphasizes greater transparency, physician educational resources, more equal distribution of liability risk and government enforcement between physicians, technology vendors and manufacturers, and positive incentives to encourage adoption of best practices.

A compromised EHR could prevent a physician from seeing a patient’s medical history, including drug allergies, historical blood pressure readings and previous medical treatments — which could lead to adverse outcomes, the American Alliance of Orthopaedic Executives said in its comments.

Devices including X-ray, MRI and ultrasound machines also need to interface with the EHR to store patient information for later reference or transfer to another provider.

“Healthcare is one of the few sectors of the economy in which a failure of our networks may mean the difference between life and death,” the group said.

Median technology costs for its members were $60,789 per practice in 2016. The executives suggested federal assistance such as tax breaks or an expense component to Medicare reimbursements to encourage adoption of new security protocols.

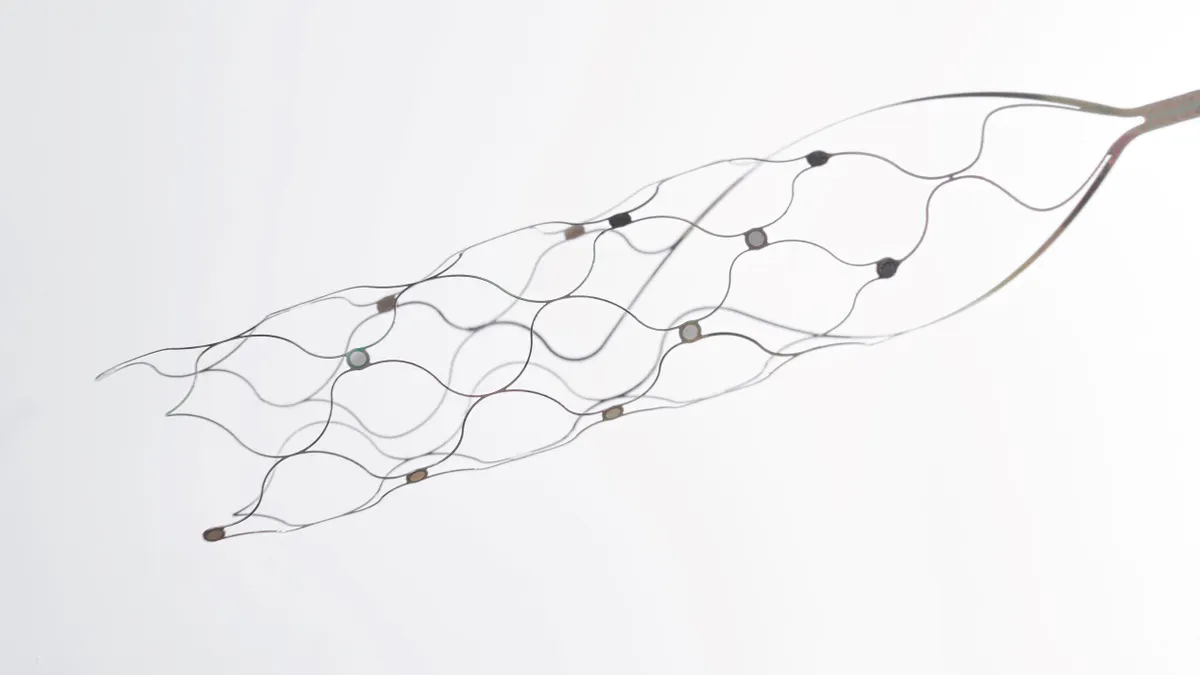

A cybersecurity risk could affect not only the security of sensitive patient information, but also the performance of medical devices that are life-sustaining, such as anesthesia machines, ventilators and therapy-delivery devices like infusion pumps, according to the American Hospital Association.

Many legacy devices were not built with cybersecurity in mind but are still clinically useful, the AHA said. For most hospitals and health systems, replacing these technologies is not financially feasible, and many can replace only about 10 percent of devices each year, the hospital group said.

Manufacturers must support end-users by wrapping security precautions around legacy devices, adding security tools and auditing capabilities, conducting regular updates, patching all software and communicating security vulnerabilities quickly through consistent channels, the AHA said.

Medical device lobby AdvaMed said any policies that would require its members to support legacy technologies indefinitely would slow development of new innovations and could influence the financial viability of smaller manufacturers.

The American College of Radiology, representing more than 35,000 radiologists, nuclear medicine physicians, radiation oncologists and medical physicists, urged Congress to “exercise restraint” in enacting any legislation that would put an undue burden on end-users such as radiologists.

“The ACR does not support government policies that would inappropriately shift more responsibility/liability associated with medical device cybersecurity away from manufacturers and onto physicians,” the group stated.

ECRI Institute, a research organization focused on cybersecurity for medical technologies, said manufacturers should be encouraged to proactively share device-specific security information such as patches and known vulnerabilities because healthcare organizations lack the knowledge to assess and manage the risk of legacy devices in their inventory.

Kaiser Permanente said policies to improve legacy system cybersecurity should strengthen the ability of healthcare delivery systems to counter current market dynamics, which it said strongly favors manufacturers.

“There are few incentives to encourage manufacturers to invest in supporting older versions of software when they can profit from the continuous need of the healthcare industry to upgrade hardware, software and (operating systems) due to obsolescence. A more level playing field will enhance cybersecurity across healthcare, help ensure greater patient safety, and improve the business value of clinical technology in healthcare delivery,” the healthcare organization said.

Device maker Becton Dickinson recommended manufacturers and healthcare organizations take a coordinated approach to improving transparency and making decisions on security patches and upgrades in response to new risks introduced during a product’s lifetime.