A medicine from AstraZeneca and Merck & Co. has become the first of its type to slow the return of a particularly aggressive, hereditary form of breast cancer, a significant finding that may push doctors to do more genetic testing in patients with the disease.

The results, from a 1,836-patient study of a drug called Lynparza, are being presented at the American Society of Oncology's virtual meeting Sunday and were published Thursday in the New England Journal of Medicine. They've been anticipated ever since AstraZeneca and Merck in February surprisingly said the Phase 3 study succeeded, without giving details. They could help change care for patients with an inherited gene mutation associated with roughly 5% of all breast cancers.

"These results will transform the prognosis, overnight, for [these] patients," said Chatrick Paul, the head of AstraZeneca's U.S. oncology division.

Patients in the so-called OlympiA trial received either Lynparza or placebo for a year of "adjuvant" treatment, meaning after surgery to remove a tumor and standard drugs such as radiation, chemotherapy or hormone therapy. All participants inherited a mutation to a gene, BRCA1 or BRCA2, and were considered at high risk of cancer recurrence because of the size of their tumor or other factors. Their tumors were either HR-positive or triple-negative, two of the three main forms of breast cancer.

Among these patients, researchers found Lynparza reduced the risk of disease progression or death by 42% compared to a placebo after a median of 2.5 years of follow-up. About 86% of Lynparza-treated patients were cancer-free, versus 77% of those who got a placebo.

Patients on Lynparza also had a 43% lower risk of developing or dying from more lethal "distant" tumors that appear elsewhere.

Those numbers are "clinically meaningful and practice changing," said Sayeh Lavasani, an assistant clinical professor at City of Hope's Department of Medical Oncology & Therapeutics Research. Lavasani wasn't involved in the trial.

Follow-up is still limited, however, meaning it's unclear how long a year of Lynparza treatment will extend patients' lives — data that Paul acknowledges is a "critical piece" of missing information.

The drug is "no walk in the park," added Debu Tripathy, the chair of MD Anderson Cancer Center's breast medical oncology department, referring to side effects like nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. In rarer cases, treatment was associated with severe anemia that can require a blood transfusion.

The authors of the study also admit they don't know how Lynparza compares to a type of chemotherapy, Xeloda, that has been proven an effective adjuvant treatment for some breast cancer patients.

Nonetheless, "this is a big win," said Tripathy, who also wasn't involved in the trial. Assuming approval from regulators, "patients with higher-risk cancers who have BRCA mutations will now be getting this."

The drugmakers aim to get the results in the hands of regulators "as quickly as possible," said Roy Baynes, Merck's senior vice president of global clinical development.

Breast cancer remains the most commonly diagnosed cancer as well as the second-leading cause of cancer death among women, despite substantial advances in treatment over the past few decades. The death rate associated with the disease declined 40% between 1989 and 2017, according to the American Cancer Society. Better early cancer detection is a big reason why.

A majority of early breast cancer patients are now cured of their disease, according to Tripathy. But about a third relapse. When they do, their cancers become much more deadly. In response, researchers have sought to bring new drugs like immunotherapies and other therapies known as CDK 4/6 inhibitors that have been approved in advanced disease into earlier settings, when they might stop cancers from returning.

Broadening use of these types of drugs comes with trade-offs, though. If cleared to lower the risk of recurrence, high-priced cancer drugs would likely become more widespread, raising costs for uninsured patients and, potentially, insurance premiums for others, Tripathy said. Insurers can block access as well; Lavasani is "hoping" they will cover Lynparza, should it be approved as an adjuvant treatment. Often, the drugs are approved on the likelihood, but not the certainty, that they'll help people live longer.

Clinicians and regulators also have to decide whether the benefits are worth added side effects for patients who tend to be younger and healthier. The FDA, for instance, asked Merck for more data when it rejected its immunotherapy Keytruda in early triple-negative breast cancer. An advisory panel was wary of the side effects associated with treatment, which Tripathy noted, can include permanent liver or kidney injury. (Merck has since gathered more data and intends to re-file for approval.)

Lynparza had what Lavasani, of City of Hope, called "acceptable toxicities," most frequently nausea and fatigue. Consistent with what's been reported in earlier testing, the only severe side effect seen in more than 5% of patients was anemia, which occurred in 79, or about 9%, of those who got Lynparza.

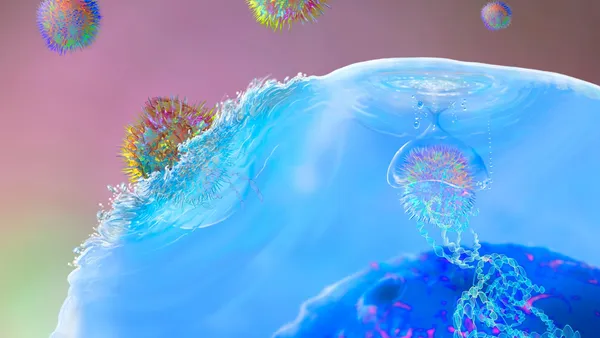

Those side effects were balanced against Lynparza's benefit in slowing breast cancer's return in patients who had inherited mutations to the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes. These patients tend to develop cancers at a younger age, have faster-moving disease and a much higher risk of relapse, some studies have shown. OlympiA study authors noted, for instance, that almost one-quarter of patients on placebo with HR-positive cancer — a typically slow-moving tumor — had invasive disease or died within three years.

There were no marketed drugs specifically tailored to BRCA1 and BRCA2 breast cancers for patients with metastatic disease until the FDA approved Lynparza and Talzenna, another, similar PARP inhibitor from Pfizer, in 2018. Those approvals came amid early enthusiasm for PARP inhibitors, which are mainly used as "maintenance" therapies in ovarian cancer.

Testing for BRCA mutations, as a result, has lagged for those with early-stage disease: 60% to 70% of patients with triple-negative tumors, and 25% to 35% of HR-positive patients are being tested, according to Ipsos Healthcare's Global Oncology Monitor.

"It's not where it should be," says Paul, of AstraZeneca.

The OlympiA results, then, could change testing practice. The data are a "call to action" to make sure patients know their BRCA status, said Merck executive Baynes.

Oncologists, Tripathy added, may push to broaden testing guidelines for patients beyond those who get cancer at a young age or have a family history of BRCA mutations.

"We would like to get to a point someday when we take the risk totally away, that having breast cancer is no longer something that can lead to fatality," Tripathy said. "We got a little closer to that with this trial."