With ventilators in short supply and U.S. COVID-19 cases first surging in mid-March, the coronavirus pandemic gave rise to a cross-industry partnership pairing automaker General Motors with Seattle area medical device company Ventec Life Systems.

Ventec, a small medtech founded in 2012, was operating at full capacity in March producing a few hundred units per month to meet the urgent need for ventilators but lacked the resources and infrastructure to increase production on a massive scale. That's when GM stepped forward offering to help Ventec build the sometimes lifesaving breathing devices at the automaker's parts plant in Kokomo, Indiana.

Within a month, the first ventilators jointly produced by GM and Ventec were delivered to hospitals in the Chicago area, according to Dan Purvis, CEO of Houston-based engineering firm Velentium, whose company provided the automated testing systems to ensure the ventilators worked as designed.

Dan Purvis, CEO and co-founder of Velentium

Permission granted by Velentium

Nonetheless, Purvis acknowledged the partnership encountered difficult manufacturing challenges early on as GM worked to ramp ventilator production from zero to 10,000 machines per month.

To state the obvious: GM is not a medical device manufacturer. It makes cars, and the scale and speed for producing the ventilators was unprecedented, Purvis observed. At the same time, he credited GM's expertise in "high-scale" manufacturing and having the purchasing power and resources of a large corporation that are "nearly second to none" as the critical ingredients for an undertaking of this size and scope.

GM and Ventec executives had their first conference calls in mid-March to discuss how the two companies could work together to ramp up production of the ventilators, Purvis recalled. That led to a March 20 face-to-face meeting between execs at Ventec's facility in the Seattle area, only three weeks and nine miles away from the nursing home where the first fatal U.S. cases of COVID-19 occurred, he pointed out during an interview with MedTech Dive.

"Four executives from GM showed up and within the first 30 minutes of them being in the building it was very obvious to me, in my 26-year career, that these people had the resources, the intensity and the intention to make a huge dent in this problem," said Purvis, who attended the meeting at Ventec's Bothell, Washington, headquarters.

Within days of that March 20 meeting, GM had engaged its global supply base, developed plans to source all the necessary parts for the ventilators, and begun preparing the automaker's closed Kokomo facility for retooling to accommodate ventilator manufacturing.

The White House had been preparing to announce the GM-Ventec venture, called Project V, that called for the production of as many as 80,000 ventilators. However, a March 26 New York Times report said federal support for the GM-Ventec partnership was called into question after the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) weighed whether the project's $1 billion price tag was too expensive, with several hundred million dollars to be paid upfront to retool GM's Kokomo plant.

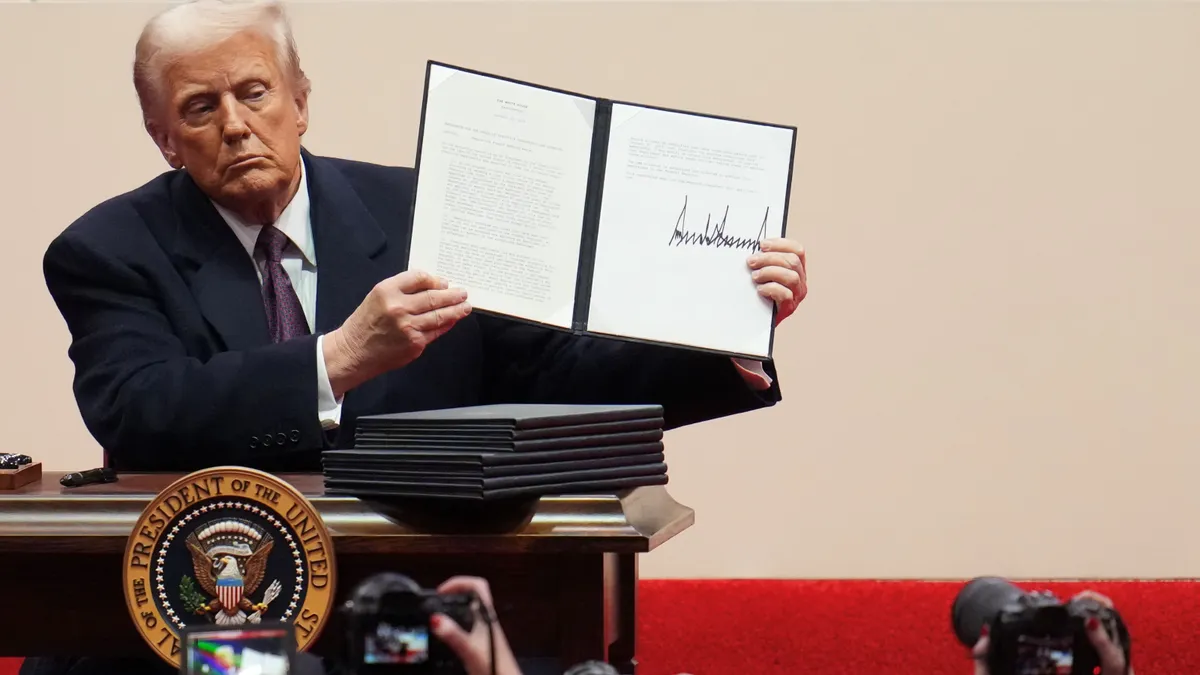

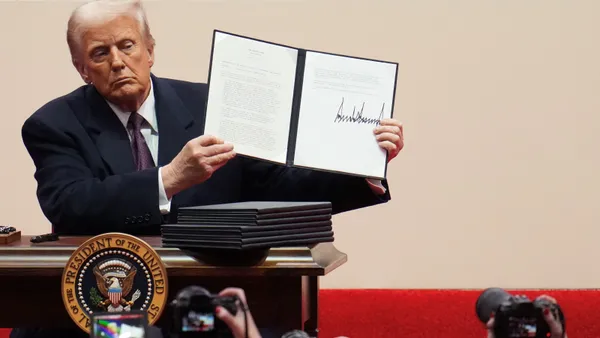

After weeks of pressure to utilize the power, President Donald Trump invoked the Defense Production Act (DPA) on March 27.

"GM was wasting time," Trump said in a statement regarding his use of the Korean War-era law to require the automaker "accept, perform, and prioritize federal contracts for ventilators."

The presidential action was followed by a $489.4 million DPA contract awarded to GM on April 8 by the Department of Health and Human Services for 30,000 ventilators to be delivered to the Strategic National Stockpile by the end of August.

Purvis said the DPA ended up being an invaluable logistics tool, giving the team the legal authority to "circumvent bureaucracy to reprioritize, redirect, and expedite orders, shipments, flights, trucks, and people" needed to get the ventilators manufactured.

"Living that DPA has been exquisite," Purvis commented. Being able to say 'I need to talk to your boss because I have a letter here that say's I'm running under an executive order from the president' certainly opened doors and loosened logjams, he added. "We never waited in any line."

Early testing, supply chain issues

Velentium is charged with testing each and every one of the 30,000 GM-Ventec ventilators as part of the manufacturing process. Initially, tests of the systems built in GM's Kokomo facility flagged problems as part of a learning process in rapidly scaling up production.

"There were plenty of issues because you've got workers hired for the task that have never built a ventilator before. There's operator learning. There's operator error. There's new suppliers that have never built these components before," Purvis observed.

"In the first day, we maybe built one or two or zero because it just takes time. But then slowly but surely you get the expertise. The suppliers start to provide good parts and the test systems start to pass things," he added.

In total, GM and Ventec required 141 test systems from Velentium to be delivered within a quick turnaround time of five weeks. "When we finished building a test stand in Houston and then shipped it up to Kokomo, it was oftentimes flown by private jet chartered by General Motors," he noted. "My testing systems were traveling like rock stars."

Hundreds of individual parts are needed to build each ventilator and the GM-Ventec team encountered inevitable supply chain challenges, Purvis said. However, the requirement for testing system parts was even more immediate, he said. "With the test systems, I needed the parts and I needed them now because I can't send a ventilator down the [production] line without the test stands."

Purvis said he worked closely with suppliers to source components from inventories around the world to ensure his access to parts critical for the testing systems. In some cases, ventilators were redesigned due to parts shortages.

"I watched the Ventec-GM partnership in those first few days redesign the VOCSN (ventilator, oxygen concentrator, cough assist, suction, and nebulizer) all in one device and pivot to the COVID-19 emergency V+Pro device which is just the ventilator," Purvis said. "If you can't get a part, and that part is necessary, then the question becomes what can we get and how could we make that part work?"