Dive Brief:

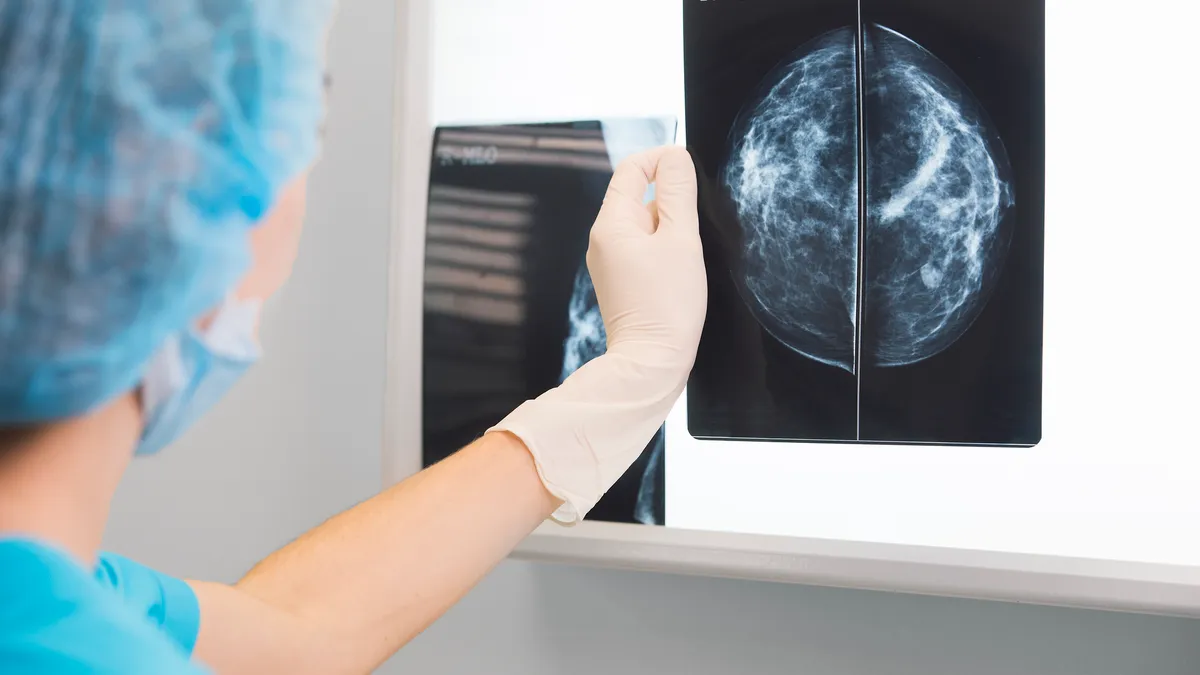

- Artificial intelligence reduced radiologists’ workload without harming the rate of cancer detection in a randomized clinical trial, suggesting the technology can be used in mammography screening.

- Writing in The Lancet Oncology, researchers reported the results of an interim safety analysis of a prospective study of 80,000 women. The trial linked the AI-supported screen-reading procedure, ScreenPoint Medical’s Transpara, to a 44% reduction in workload.

- The study is continuing to collect data for its primary endpoint but, based on the interim results, the investigators concluded the procedure is safe and could help address radiologist shortages.

Dive Insight:

Multiple retrospective studies have found AI can improve the accuracy of mammography screening and reduce the time radiologists spend reading scans. The studies suggested AI may be better at detecting interval cancers, tumors that are diagnosed in between screening episodes, and eliminate the need for two radiologists to review every scan. Yet, the lack of prospective data left room for doubt.

Researchers with Lund University in Sweden started the first randomized controlled trial investigating the use of AI in mammography screening. It was funded by the Swedish Cancer Society, Confederation of Regional Cancer Centres, and the Swedish governmental funding for clinical research.

The study randomized 80,000 women to undergo standard double mammography reading or AI-supported screening. Participants in the AI arm were assigned to single or double reading based on the malignancy risk score provided by Transpara.

An interim analysis of the study looked at secondary outcomes including the cancer detection rate and screen-reading workload. The cancer detection rate per 1,000 participants was 6.1 in the Transpara arm, above the lowest acceptable limit for safety, and 5.1 in the control group. The false positive rate was the same in both cohorts, suggesting AI may detect more cancers without causing unnecessary follow up.

The study linked the AI to reduced radiologist workload too. Because participants in the Transpara cohort only underwent double radiologist readings if the AI classed their scans as high risk, 36,886 fewer screen readings were done in the intervention group than in the control arm. The figure translates into a 44% reduction in the screen-reading workload.

In a statement, lead author Kristina Lång from Lund University said AI “could potentially do away with the need for double reading of the majority of mammograms,” easing the pressure on radiologists and shortening waits for patients. However, Nereo Segnan from Piedmont Reference Center for Epidemiology and Cancer Prevention, used an accompanying comment piece to call for caution.

The results may “seem straightforward in favoring the use of AI,” Segnan wrote, but the data reveal the “possible presence of overdiagnosis (ie, the system identifying non-cancers) or overdetection of indolent lesions.”

The upcoming final results of the trial, which is primarily testing whether AI improves detection of interval cancers, could provide a clearer picture of the merits of the technology.