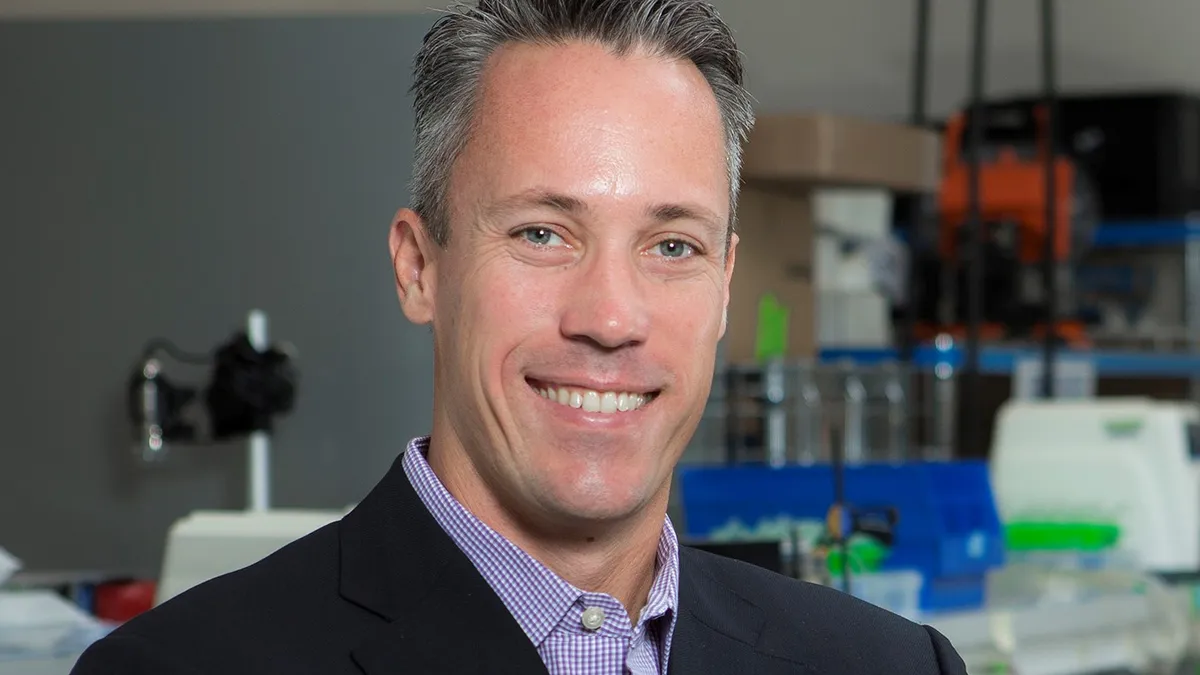

Steven Mickelsen, the electrophysiologist who founded Farapulse before it was sold to Boston Scientific in 2021, is taking pulsed field ablation into new territory with the development of a device that uses the energy source to treat ventricular tachycardia.

Mickelsen invented the technology that became the Farapulse PFA system while a professor at the University of Iowa. The device is now helping transform the treatment of atrial fibrillation, an irregular heart rhythm that increases stroke risk. Offering a potentially safer way to ablate the cardiac tissue that causes AFib, PFA systems were among medtech’s biggest new products in 2024. PFA is on track to be used in more than 60% of AFib procedures by 2026, according to Boston Scientific, supplanting older approaches such as radiofrequency ablation.

In his current role as CEO of Field Medical, Mickelsen has turned his focus to building a PFA tool to tackle VT, an arrhythmia that can lead to sudden cardiac death. The California-based startup’s FieldForce PFA device received the Food and Drug Administration’s breakthrough device designation in December and was accepted into its total product life cycle advisory program designed to bring important medical technologies to patients more quickly. Human testing is underway.

Mickelsen spoke to MedTech Dive about PFA’s origins and why he sees the technology as the answer to an unmet clinical need.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

MEDTECH DIVE: Where did the idea for Farapulse come from?

STEVEN MICKELSEN: Being the founder of Farapulse in 2012, I started working on how do we make atrial fibrillation ablation safer?

People were having esophageal fistulas, dying from that. People were having phrenic nerve injury. We have complications that, although very rare, are very awful complications in these procedures. I don't care if it's only one in 1,000 or one in 10,000, can we justify that?

I started a company called Iowa Approach that became Farapulse, and focused on how do you improve the outcomes of these people? And that's where pulsed field came in.

I looked at every technology out there, and I found this old concept of doing direct current ablation actually has a huge advantage for safety and efficacy, and I started playing with it, and it turns out it was the right thing to do. Farapulse was acquired by Boston Scientific. People talk about technologies that are disruptive. This one is. It is an amazing first-generation technology. It’s the pioneer technology, and I’m very proud of it.

Why is the time right to work on a PFA approach for treating VT?

I had an opportunity to ask another question, which is, now that everybody and their mother is going after AFib ablation, why aren’t we addressing the people who are dying from VT — when we know that catheter ablation is more effective than anything, and nobody is working on great VT tools? And so that is the birth of Field Medical. I have a true unmet need, and it’s an open ocean.

Ventricular tachycardia is when the bottom chamber of the heart goes super fast — so fast that it's no longer an efficient pump. Then when blood pressure falls, you don't get perfusion, and people die from this. VT is more common in people who've had prior heart attacks or have another chronic condition or genetic predisposition that leads to electrical instability of the muscle itself.

Patients who have had prior heart attacks are at high risk of having electrical instability because that scar is no longer contributing to the squeeze of the heart. If you look at the scar carefully, you'll notice that there are little areas of heart muscle that are alive. It's no longer contributing to the contraction of the heart; it's stuck in the scar itself. And what happens is, one of these little areas of live muscle that's abnormal, but sitting inside the scar, is the source of the VT.

When we identify patients who have these problems, we have a few options. One of them is drugs. One is implantable cardioverter defibrillators, which have been a revolutionary technology. ICDs don't prevent VT from happening, but should it occur, it's a safety net.

Drugs are the first-line therapy we have for VT. All of them are super toxic, and they’re actually not very effective. Many, many electrophysiologists believe the drugs themselves are not doing that good of a job.

So there is a lot of motivation to find a better way.

How can PFA improve treatment for VT?

Today the average VT ablation is four hours, and everyone considers it a complex ablation. It's hard to do because the tools are really optimized and built for atrial procedures. So we're going to build tools that are capable of democratizing VT therapy.

I know I can't do that unless we can make these procedures predictably short and safe and effective. We started with that premise. We need a focal catheter. But we need one that has reach, one that can be for full-thickness left ventricle lesions, because there's scientific data that shows that if you are doing scar-related VT and you ablate on the outside and the inside of the heart using a radiofrequency catheter, the outcomes for the patients are substantially better.

But the problem with that is technically, it's very hard to get to the outside of the heart. Most doctors who do electrophysiology procedures don't routinely do that, and it's a limited number of available centers in the United States and Europe. And so, what if we could just reach it from the inside of the heart and not have to go to the outside of the heart? Well, that would require a tool that had a type of energy that we just don't have today.

And it turns out, pulsed field is ideal.

How does PFA address the technical challenges in VT?

It is ideal because of the complex shape of the heart. The left ventricle itself is not only thick, but the inside layer is full of complex shapes that could be a part of the VT circuit.

The standard of care now for scar-related VT is to do a procedure where you map it, you figure out electrically where everything is coming from, and you zap it with a radiofrequency catheter. You either go to the spot where it's happening and only ablate that little spot, or you take a procedure where you say, I want to turn it all into only scar and get rid of this electrically unstable heart tissue that's stuck inside the scar. That's called substrate homogenization.

That strategy is the one that I'm looking at the most right now. You identify the limits of the scar so you don't damage the tissue that is contributing to the contraction of the heart, but you get rid of that abnormal, electrically unstable tissue that is stuck inside the scar. The beauty of PFA is you can do it in a very clean way. It heals incredibly fast. Within two weeks or so, most of the ablation is well on its way to healing. Today, with radiofrequency catheters, it just takes forever moving it around, trying to find a spot, and it takes months and months to fully heal.

The tool that we've built is very much like a radiofrequency catheter. It handles like one. It has contact force and magnetic navigation should you want to use it. So no training is required. The difference is the energy it delivers.

I want to take that procedure and turn it into a one-and-a-half-hour outpatient procedure for people who already have ICDs. I think we can achieve that goal, based on the data that we see now, and that will be transformative in the ventricle in much the same way that Farapulse is transformative in the atria.