Leadless cardiac pacemakers do away with the electrode wires, known as leads, that connect the device to the heart to treat slow or irregular rhythms. Over the years, leads in traditional pacemakers have been associated with complications that include fracturing, insulation defects, and infection in the surrounding tissue. They can be difficult to remove.

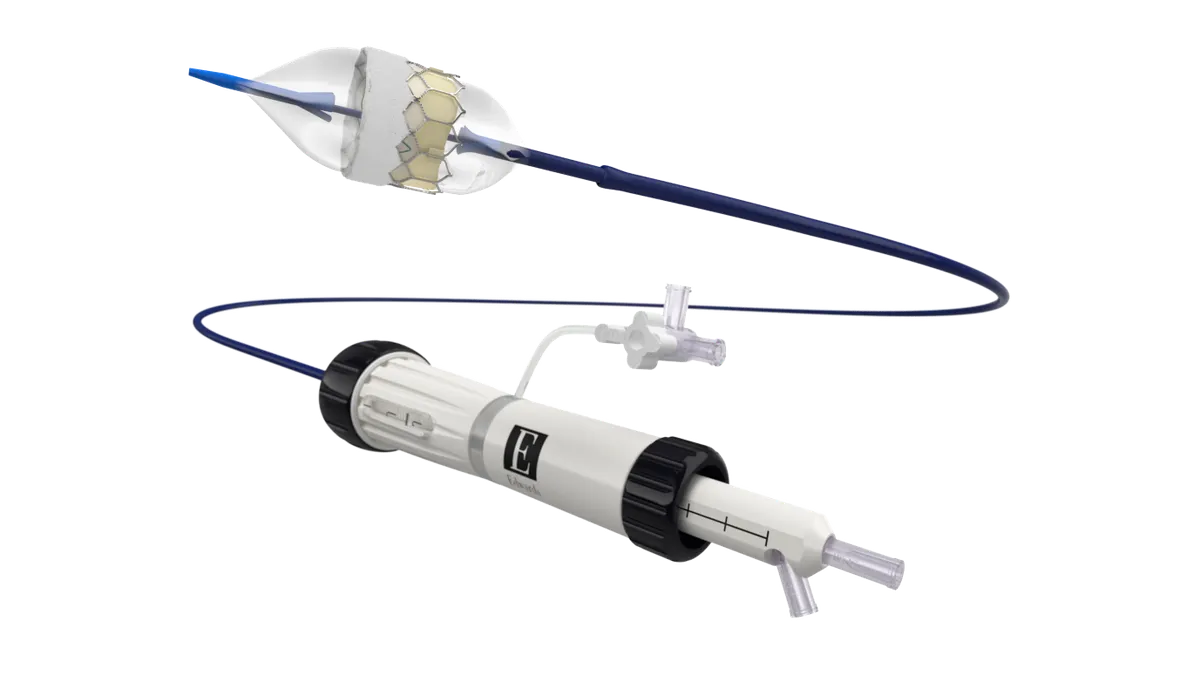

The Food and Drug Administration approved the first leadless pacemaker in 2016, from Medtronic. Now, Abbott aims to take a large share of the growing market for leadless pacemakers with the rollout of its Aveir offering, which gained FDA approval in March 2022. The new device “has an opportunity to really reset our growth trajectory in the CRM [cardiac rhythm management] space,” Abbott CEO Robert Ford said this year at the J.P. Morgan healthcare conference.

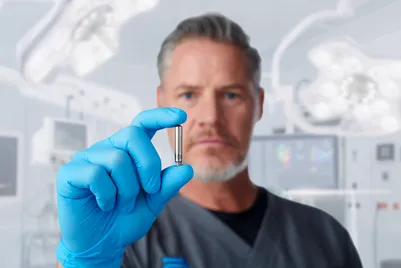

The leadless pacemaker is implanted directly into the right ventricle of the heart through a minimally invasive procedure. Abbott is also working on a dual-chamber version that executives see addressing an even larger market opportunity.

Vish Charan, divisional vice president of product development at Abbott’s cardiac rhythm management business, told MedTech Dive that leadless pacemakers could become the new standard of care in pacing.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

MEDTECH DIVE: How has technology advanced to develop a pacemaker that doesn’t require leads to attach to the heart?

CHARAN: A cardiac pacemaker in its traditional form is a pulse generator which is implanted into the chest. You have an electrode wire called the lead that connects from the pulse generator – which is a titanium can under the chest – to inside the heart. In the traditional pacemaker, you would create a pocket under the chest for the pacemaker to go in, and the patient would always know and always feel a pacemaker in their upper chest.

A leadless pacemaker is taking the pulse generator and making the size not just a 10% reduction or a 20% reduction, but making it a 10-fold reduction from what a traditional pacemaker is. I’ll give examples: It's not just making a smaller watermelon but taking a watermelon and making it a lemon and dropping the size significantly, and it does take a lot of technologies to do that. And then you downsize this technology, and the pacemaker now has the electronics and the battery inside a titanium shell, and it is deployed with delivery tools, directly into the right locations of the heart, for sensing and pacing of the heart.

Pacemakers were first developed in the ‘50s and have been in existence for a long time.

It's always good for whatever you put into the body to be extremely small.

Vish Charan

Divisional vice president, Abbott

Myself, I've been at St. Jude Medical/Abbott now for 20 years and have seen the evolution of change, and it's a really exciting time for the pacing industry as a whole, and leadless pacemakers are one big segment in that.

How does leadless technology address complications that have occurred with leads in the past?

It's always good for whatever you put into the body to be extremely small. Making things miniaturized is always the goal, independent of whether you have a problem or not. You provide the therapy but you do it in the most efficient way.

Lead challenges, which stemmed from the late 2000s and progressed for a little bit, drew additional motivation for innovation in this space, but it's always been a motivation to make devices smaller. You’ve got to have the right time, you’ve got to have technology which is moving, and you’ve got to have the right innovation and you’ve got to have the right market need to bring these together. And it was very timely where the industry started to drive towards leadless pacemakers, where we invested significantly into this.

What other improvements have been designed in this new generation of pacemakers?

Battery life is extremely important because you're putting a pacemaker, or any device, into the human body, and you're expecting it to last a long time. And the more times you have to go to get it out or change the battery, you are bringing a patient into a procedure which nobody wants to do, and it just creates more risk.

There are only two commercially available leadless pacemakers in the market, and the pacemakers that we have, the Aveir pacemakers, have up to two times longer battery life than the other leadless pacemaker on the market. The industry looks at what we call ISO, International Organization for Standardization, settings, and when we do that, we have improved battery life from our first generation to the Aveir pacemaker. And now for the single-chamber Aveir VR pacemaker, we have shown data which is nearly 17 to 18 years of life on the typical pacemaker patient, when we looked at the one-year follow-up of clinical trial results.

If the leadless pacemaker needs to be removed, how is that done?

We are the only leadless pacemaker which is designed in a way that you can chronically retrieve it, over a period of time, in a patient. They are designed with what we call a screw, or a helix, like in carpentry. You could screw in a screw and you could screw it out with a screwdriver. And that is the design concept behind these Aveir leadless pacemakers. We have shown in the Nanostim, which is the first-generation product that is not market-available now, that we have taken out pacemakers over eight years, over nine years, of patient life. Abbott provides a retrieval catheter, which is similar to what you use for delivery, but it is now here to go grab onto the pacemaker and rotate it out, and bring it out of the body extremely safely. The competition has a very different technology which doesn’t allow for a helix or a screw-based fixation.

In what other ways does Abbott’s Aveir pacemaker differ from competing devices?

Another difference is the ability to do what we call mapping. It is electrically knowing where in the heart you are before you deploy the pacemaker in the heart. With the pacemaker at the end of the catheter, you're able to position it at various locations in the heart, and then get electrical readings of sensing and then pacing, so that you could decide whether this is the best location for the patient. Once you decide it's the best location, then you deploy the pacemaker into that location.

The last thing which I would say is the most significant aspect for the future – because leadless pacing technology, as we have defined it, is a platform technology – it's not just one and done – is we have the ability to do multi-chamber pacing, put multiple pacemakers in the heart that communicate with each other. That's a technology in investigation. It's right now in a global clinical study which we started early last year, so that's where we are at with that. And I would say we're just getting started.

Will leadless pacemakers eventually replace traditional pacemakers? How do you see that evolving?

What I can tell you is that leadless pacemakers are growing significantly. Pacemakers, as we all know, are a very mature technology, and we're bringing in a brand new technology with a brand new device into the market. The industry is bringing it in. It's at the early stage of adoption, so that's also why it is exciting. It's really exciting. And as we develop new features, we bring in new capabilities, multi-chamber pacing, new abilities to pace into new therapy areas like conduction-system pacing, and we improve physician training – because this is now transcatheter-based deployment. It is very different from the traditional way of implanting a pacemaker and a lead. There is a physician training component. We believe that it could become standard of care.