This story is part of a MedTech Dive series examining the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the medtech industry, published one year after the start of the crisis. You can find the other stories here.

To say that 2020 was a challenging year for FDA would be an understatement. The COVID-19 pandemic stretched resources thin as it grappled with unprecedented regulatory demands as a result of the U.S. public health emergency.

FDA’s response to the coronavirus crisis focused on increasing availability of testing, therapeutics and vaccines, as well as medical devices such as ventilators and personal protective equipment.

Despite these challenges, FDA in 2020 approved, cleared or authorized a record 132 novel medical devices, topping the 106 novel device authorizations in 2018 that marked a 40-year high.

Jeff Shuren, director of the Center for Devices and Radiological Health, has said this year will be more of a "reset" as CDRH looks to both manage coronavirus-related work and move forward with projects outside of COVID-19.

FDA is operating in 2021 with the benefit of lessons learned during the first year of the pandemic. However, the learning process has been rocky, as evidenced by a recent admission by CDRH that its policy of allowing COVID-19 antibody tests on the market without undergoing regulatory review was "flawed."

Here's what to expect as the agency grapples with balancing COVID-19 priorities, as well as those that may have gotten shifted during the historic year.

COVID-19 remains the top priority

The U.S. public health emergency will no doubt be extended by the Biden administration throughout 2021 and COVID-19 will remain a top priority, particularly with the emergence of more contagious and deadly SARS-CoV-2 variants.

That will keep significant resources on review and oversight of coronavirus-related devices, including tests, as well as issue enforcement guidance that reduces the burden on device makers.

"Pandemic, pandemic, pandemic. Those are the three Biden priorities for FDA right now. Obviously, that impacts vaccines but it also impacts COVID testing, which has had an up -and-down history when CDRH made some early missteps," said Jonathan Kahan, partner at law firm Hogan Lovells.

As of the end of February, FDA has green lit more than 330 COVID-19 tests and sample collection devices through emergency use authorizations, with nearly 250 EUAs granted to molecular diagnostics alone.

The agency is now assessing whether existing COVID-19 tests are able to detect new variants and last month published guidance on evaluating the impact of coronavirus mutations on tests, including the potential for false negatives.

Testing priorities also include at-home tests and home collection kits, as well as point-of-care diagnostics and tests that can be performed in high volume in central labs. FDA has granted a small number of EUAs for at-home molecular and antigen tests, some requiring prescriptions and others over-the-counter, a trend that will continue in 2021.

"We are not out of the woods and therefore there is going to be continued need for devices that help either diagnose or treat COVID-19," said Scott Danzis, partner at law firm Covington & Burling, who sees FDA putting particular focus on getting at-home tests into the market.

Increase in FDA enforcement activity

The Trump administration was relatively consistent in its drive to deregulate. Legal experts now anticipate an increase in FDA enforcement activity.

Kyle Faget, partner at law firm Foley & Lardner, expects a focus on evaluating companies for compliance with their EUA Conditions of Authorization such as reporting product performance issues.

FDA this year will be in a position to "address those issues more readily" because the agency "has its arms around the pandemic a bit better" than in 2020 and there is a shift in focus underway with the Biden administration.

"What you saw under the prior administration was this concept of a kinder, softer FDA to industry," said Dennis Gucciardo, partner at Morgan Lewis, who echoed the expectation of a shift under Biden.

Non-compliant activity that would be handled through non-public, informal correspondence under the Trump administration may trigger formal public enforcement actions such as warning letters and consent decrees under the Biden administration, according to Gucciardo.

FDA warning letters to medical device manufacturers plummeted by nearly 90% between 2015 and 2019. And, last year's rate of typical warning letters was roughly in line with 2019 numbers. However, experts say such letters are set to rebound in 2021.

"Enforcement is absolutely going to increase," Kahan said. "We're going to see more inspections, more warning letters, and we may see more enforcement actions coming up."

FDA last year postponed all domestic routine facility inspections in response to the COVID-19 outbreak for about four months to protect its inspectors and address industry concerns about on-site visitors. The agency only restarted some of those on-site visits within the U.S. at the end of July.

Gucciardo expects to see an increase in "for cause" FDA inspections in 2021, similar to what companies experienced under the Obama administration when "a lot more action" was driven by allegations made by consumers and consumer groups. "Under the Trump administration, we didn't really see that kind of activity unless there was a public health threat," he added.

Danzis also predicts on-site inspections will ramp up this year. At the same time, he points to IMDRF's Medical Device Single Audit Program (MDSAP), in which FDA is a participating member, as a potential alternative for the agency's routine inspections.

Under the program, a MDSAP recognized auditing organization can conduct a single audit of a medical device manufacturer that satisfies the relevant regulatory requirements. FDA last month said it will accept MDSAP audit reports as a "substitute" for routine agency inspections.

Longer term, Gucciardo said with "seasoned device companies" opting to participate in the voluntary third-party MDSAP he expects FDA's "inspection cadre, which has not reduced in size, to inspect promptly new firms that recently received premarket clearance and potentially firms marketing 510(k)-exempt devices."

For now, Faget sees FDA in 2021 releasing its long-awaited publication of the revised Quality System Regulation which is intended to be harmonized with ISO 13485, a set of requirements for medical device quality management systems, and will be subject to evaluation in FDA inspections. The agency has missed a number of target dates for QSR, a series of delays that "have people worked up" and could serve as the tipping point, she added.

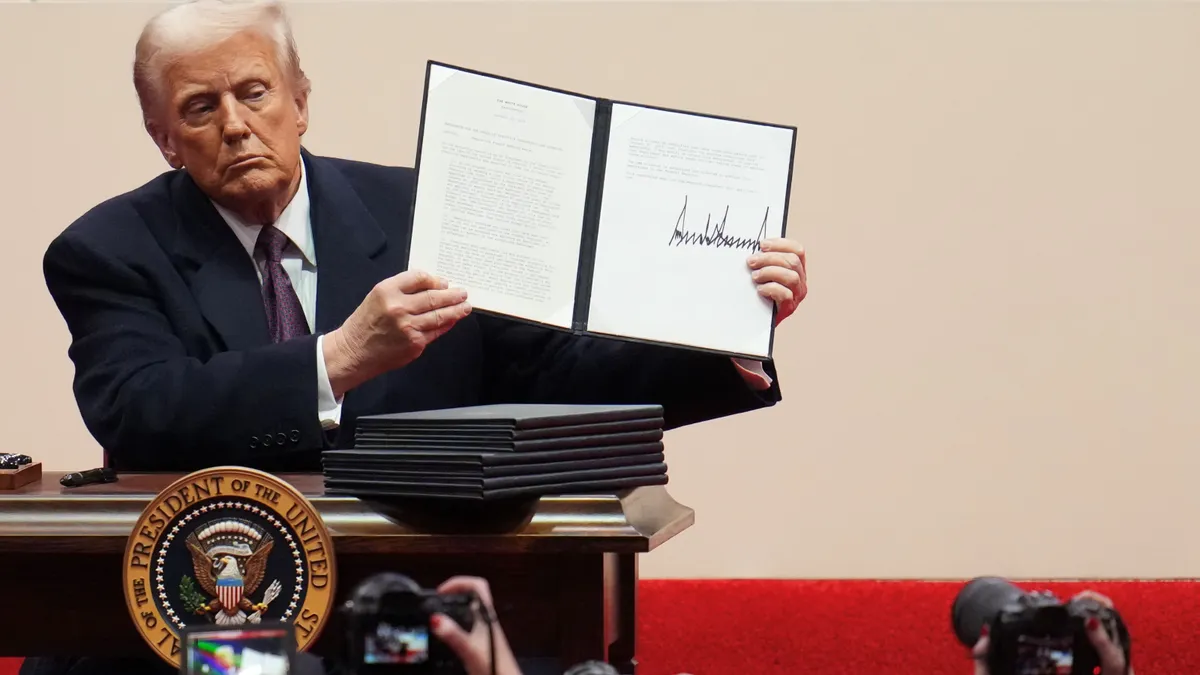

Roll back of Trump orders, regulatory reform.

Biden wasted no time in rolling back Trump's executive actions, revoking Executive Order 13771, entitled Reducing Regulation and Controlling Regulatory Costs, on his first day as president.

That early 2017 order directed all departments and agencies that planned to publicly announce a new regulation to propose at least two to be repealed. Critics argued it harmed the public by forcing agencies to focus on costs rather than benefits and forcing them to repeal beneficial regulations while arbitrarily preventing new regulations to be passed.

Another Trump-era effort expected to be rolled back is an HHS proposed rule from November 2020 requiring the department, including FDA, to review relevant federal regulations every 10 years, with an automatic sunset provision for such regulations if the required assessment and/or review were not completed in a timely manner.

While HHS proposed the rule during the pandemic when many employees are focused COVID-19 response, it said in November's proposal that the department has "been able to continue moving forward on a range of priorities to enhance and protect the health and well-being of the American people" and that the proposed rule "is not expected to increase burdens significantly on HHS."

However, according to Kahan, the reality is that there are 18,000 HHS regulations, two-thirds of which would need to be reassessed under that regulation. "Somebody will have a lifetime career of reviewing those. I think [the Biden administration] is going to reverse that too," he said.

Danzis also sees the Biden administration revoking, rescinding or otherwise changing that kind of "broad brush stroke, forcing mechanism" approach in the HHS proposed rule in favor of more "nuanced" policies that don't "tie the hands" of the FDA and other agencies.

LDTs: A shock, but fate uncertain

HHS shocked the industry in August when it announced FDA would no longer require premarket review for laboratory developed tests (LDTs). At the time, the Trump administration defended the change as part of its ongoing review of regulatory "flexibilities."

HHS immediately faced widespread criticism. While some test developers question FDA jurisdiction, the agency has long maintained that these tests are devices and fall under its purview according to the Medical Device Amendments of 1976.

In addition, the policy change was issued by HHS, and not FDA, drawing the attention of industry observers who saw it as evidence of internal divisions, with then-HHS Secretary Alex Azar reportedly overriding objections from FDA on the easing of rules applicable to all LDTs covering a wide range of diseases including cancer and COVID-19.

Although FDA initially required premarket review of COVID-19 LDTs in response to the pandemic via the EUA pathway, HHS in its August announcement no longer required premarket review but said labs could voluntarily seek approval, clearance or emergency use authorization.

The drama continued in October when FDA said that it would no longer review EUA requests for COVID-19 LDTs, only to have HHS reverse the FDA's decision in November by ordering the agency to provide "timely" EUA reviews.

"What we saw a lot of in the Trump administration was HHS getting very involved in FDA's business and we're going to see less of that” with the Biden administration, said Faget. “There’s going to be much more deference to FDA as an independent regulatory body."

Still, legal experts are split on whether the Biden administration will seek to reverse the policy announced in August by HHS asserting FDA does not have regulatory jurisdiction to require premarket review of LDTs and that these tests do not need to undergo pre-market review by the agency.

Danzis is not convinced that the Biden administration will reverse the HHS policy, suggesting they may instead focus on legislation introduced in Congress, which he says has the potential of "settling the issue" in terms of FDA authority.

Prior to the HHS policy change in August, Congress had been working on the regulation of LDTs. The Verifying Accurate, Leading-edge IVCT Development (VALID) Act introduced in March 2020 in both the House and Senate creates a new test product category — in vitro clinical tests, which includes lab-developed tests — while giving FDA authority to review and approve IVCTs.

Faget believes the VALID Act would be a relief for industry because at the very least it would provide "some certainty."

While Kahan acknowledged a slight chance that legislation such as the VALID Act could be passed into law in 2021, he contends that FDA isn't going to wait for lawmakers to take action.

The agency "has forever said it has authority over LDTs," according to Kahan. "There's 100% chance that whomever the commissioner is, or whomever the CDRH director is, that will be reversed."

Digital health continues to be priority

The pandemic spurred demand for digital health technologies such as artificial intelligence, remote patient monitoring and telemedicine. FDA in September launched the Digital Health Center of Excellence to better coordinate policy and regulatory approaches tailored for the fast-growing technologies, promising to provide "efficient and least burdensome oversight" while meeting "standards for safe and effective products."

Legal experts anticipate FDA's efforts in the area will continue under the Biden administration.

While the Trump administration developed guidance and policies for digital health, including software exemptions under the 21st Century Cures Act and COVID-19-related documents, FDA has been slow to finalize guidance for both clinical decision support (CDS) and AI/machine learning.

FDA has yet to issue its much-anticipated final guidance for CDS software, after releasing draft guidance in September 2019 which was the agency’s second attempt having issued prior draft guidance in December 2017.

In addition, it's been nearly two years since FDA's April 2019 discussion paper on a regulatory framework to enable ongoing AI/machine learning algorithm changes to software as a medical device (SaMD) based on real-world learning and adaptation.

However, a week before Biden's presidential inauguration, FDA released an action plan for establishing a regulatory approach to AI/machine learning-based SaMD. That comes amid calls for regulatory clarity from AdvaMed and others on machine learning algorithms that continually evolve without the need for manual updates. FDA so far has approved or cleared only devices that use "locked" algorithms that do not change in this way.

“What regulated industry wants is some certainty and a clear understanding of what the rules of the game are,” said Danzis.

CDRH in October released its list of proposed guidance documents for fiscal year 2021 in which it assigned a lower Category B priority for the Pre-Determined Change Control Plan: Premarket Submission Considerations for AI and Machine Learning Software draft document. The B-list, which includes guidance documents that the FDA "intends to publish as resources permit," has put a low priority on the change control plan, seen as the cornerstone of FDA's new approach to AI.

Kahan said his medtech clients are frustrated that FDA has yet to finalize various guidance documents in the area of digital health and AI. However, he contends the lack of agency progress isn't stopping manufacturers from developing products that are "in line with what they deem is appropriate within existing guidance."

Developers can take an “ultra-conservative” approach or operate “with a certain amount of regulatory risk” in trying to get their digital health products to market in the absence of final guidance, according to Faget. But she also notes that problems can arise when FDA is not clear in what it expects from device makers.