When Kevin Sayer joined diabetes medtech Dexcom as president in 2011, the company was gearing up to change manufacturing processes for its continuous glucose monitor sensors that would enable a "growth spurt."

Between his first two full years on the executive team, expansion in Dexcom's G4 product supported a 60% rise in annual revenue to $160 million.

Today, Dexcom finds itself in a similar position, overhauling manufacturing for its latest take on CGM, called G6, amid projections it will close out 2019 with up to $1.45 billion in revenue. Its stock price has nearly doubled since the year began.

Such a revamp is a bit different as a larger company.

According to Sayer, who took on the CEO role in 2015, many of the CGM system pieces that Dexcom manufactured stayed the same between 2006 and 2018. The insertion technology and plastics remained constant while sensor wires, membranes and software evolved across product iterations.

But last year when FDA approved G6, "every physical feature of our system changed," he said, necessitating more automated, consistent manufacturing.

Dexcom's 2020 will largely center on meeting demand for G6 (sensor production capacity is set to quadruple between the end of 2019 and next summer) as it simultaneously preps to begin rolling out its latest G7 technology near the close of next year.

Sayer offered a few more details on what the next year might look like for Dexcom in an interview with MedTech Dive.

Dexcom will go after consumers more aggressively

The swell in interest in CGM and automated insulin delivery systems more broadly has been a rising tide that's lifted all boats.

Some of that has come from competitor Abbott's marketing of its FreeStyle Libre CGM, sales of which grew more than 60% in the most recent quarter.

While Dexcom has done some TV and magazine advertising, Sayer said marketing has largely been consolidated in digital formats, considering the time patients spend researching potential therapies.

“We've not turned on the faucet full blast on the direct-to-consumer campaigns, simply because … we've grown $300 million-plus so far this year; I don't know how we could have grabbed a whole lot more," he said.

But Sayer intends to change that tempered approach.

"One of my objectives as the leader of this company is when we get that capacity up, I want to challenge our people to really go much harder after the consumers directly."

2020: The year of both G6 and G7?

The company is aiming to hit the ground running in late 2020 launch of G7, co-developed with Google's Verily to be fully disposable and smaller than a quarter.

Sayer was quick to emphasize the company is not abandoning G6. "It's not going to go away because of G7," he said. "We think we can rechannel it into other areas, and there's more to come on that without revealing our entire strategy behind it."

How Dexcom will position the still relatively new G6 in relation to G7 once both are on the market is a work in progress.

Some geographies will stay on G6 "until we're absolutely ready" to introduce G7, Sayer said. But in regions where Dexcom isn't yet doing business, like China and certain other parts of Asia, G7 could likely be the inaugural product launched.

The sensors for G7 will be the same as G6 "but everything else is going to be different," and will require entirely separate manufacturing lines, Sayer said. With the ability to scale front of mind, the product was conceptualized to be "highly manufacturable."

"If we've learned anything from G6 and this scale-up experience, we're going to make sure for G7 we're ready to go," Sayer said. "Everybody who works here is going to hear from me on manufacturing ramp each and every single day."

Looking for more partnerships

Industry has heard FDA's desire for interoperable platforms loud and clear, Sayer said.

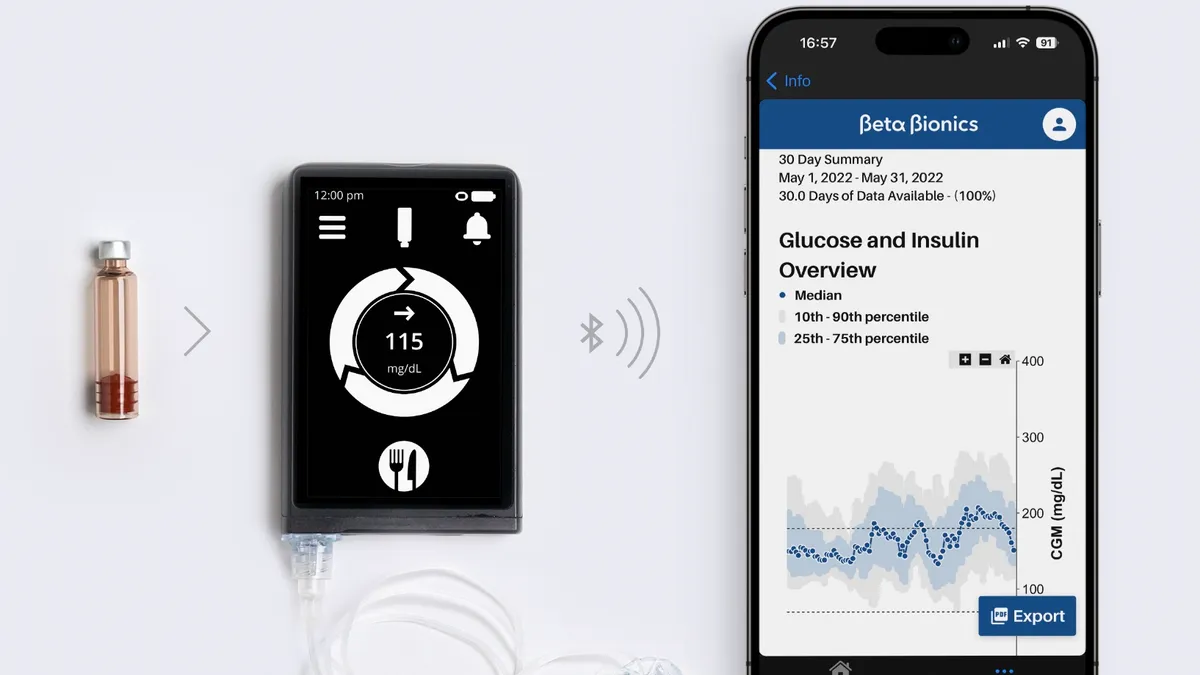

With G6, Dexcom was the inaugural company to achieve the agency's integrated CGM, or iCGM, designation, meaning it is authorized for use with similarly interoperable electronic devices used to manage diabetes like insulin pumps or automated dosing systems.

Still, "it is not as easy as it would appear" to make medical devices talk to each other effectively, Sayer said.

But the company's engineering work has led to collaborations with connected insulin pen makers such as Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Companion Medical as well as insulin pump manufacturers like Tandem and Insulet.

That list will likely only grow.

"Our goal, obviously, is to sell more sensors. So if we can get more sensors on more people and talking to other platforms — we will consider it as long as it makes regulatory sense and makes sense for our business models."

Pushing payers to expand access for Type 2

Dexcom has had its fair share of reimbursement wins, with Medicare and many major insurers offering CGM coverage for people with Type 1 diabetes.

Still at the top of Dexcom's reimbursement wishlist? Easing access to the technology for people with Type 2 diabetes who take insulin. "Payers have been slow to come to that," Sayer said.

And within the better-covered Type 1 population, the bar to initiate CGM therapy can still be burdensome. Sayer described cases of parents manipulating insulin and sugar dosing to document hypoglycemic events to submit to insurers in bids to qualify for coverage.

"I just find this barbaric," Sayer said. "I know why payers do it; they try and control costs and make sure people really want the technology. But our technology is at a point where, really, for somebody using intensive insulin therapy, this should be the standard of care."

A five-year plan: Health and wellness?

When it comes to how Sayer plans to spend the next 12 months, "I think the most important thing in my job is to position us to be where we need to be over the next five years," he said.

Ideally for Dexcom, those next five years might see CGM become a first-line technology for individuals with Type 1 diabetes who are either pregnant or admitted to hospitals, or people with non-intensively managed Type 2 diabetes who could use it as a behavior change tool.

And in a shift that would blow open CGM's addressable market, the same tech design used to sense blood glucose levels could potentially be used to track other analytes. Without going into much detail on which substances might be a good fit, Sayer noted the technology can appeal to athletes and people interested in general "health and wellness" and learning more about their metabolism.

For many of these goals, "we're at the place we were in intensive insulin therapy when I got here eight years ago," Sayer said. "It's now time to go embark on some of these other journeys while my team has this intensive space in a really good place."

Might there come a time when CGM isn't viewed only as a diabetes technology?

"Absolutely," Sayer said. "We definitely envision that day."