Osseus Fusion Systems' 3D printed titanium spinal implants won FDA clearance earlier this year, joining more than 100 devices and one drug currently on the market manufactured on 3D printers.

FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb has called 3D printing a transformative technology that could disrupt medical practice, and the agency is scrambling to keep abreast of new regulatory challenges.

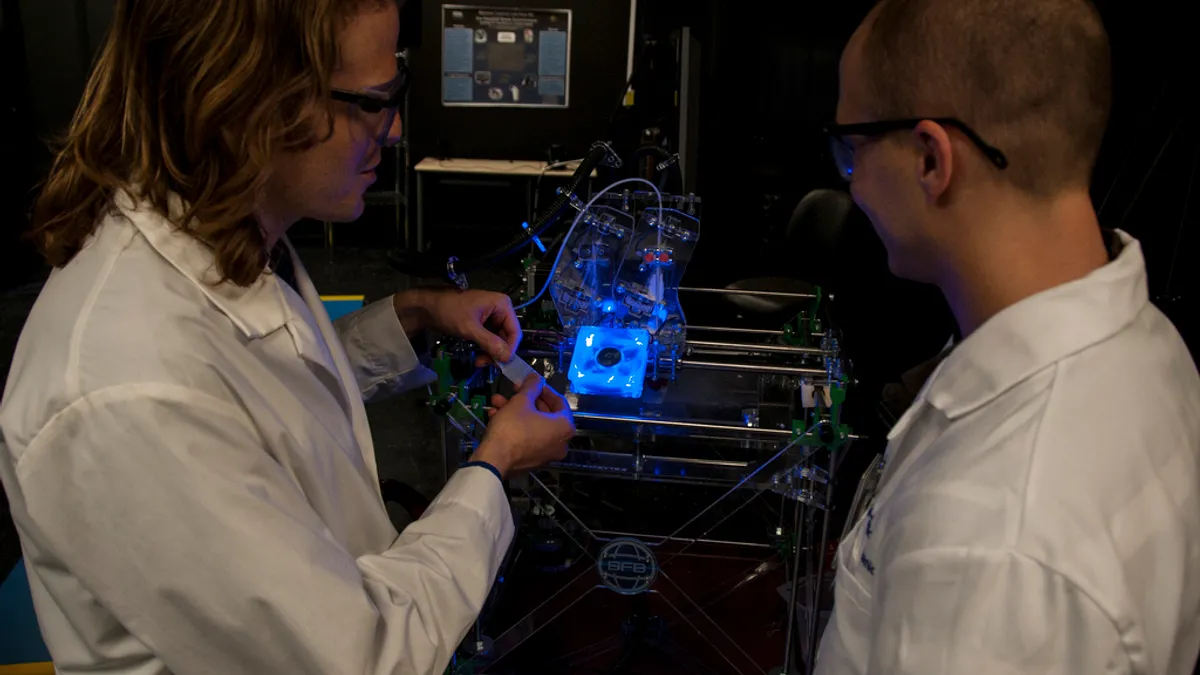

Known as additive manufacturing, the process involves production of three-dimensional objects using a digital file. The printer layers successive images or files on top of one another until a solid 3D object is formed. The process allows designers to create 3D models of a patient's anatomy for use in diagnosis or surgical planning. The technology is also being used to customize orthopaedic implants and accessories, prosthetics, hearing aids, dental implants and wearables, such as flexible sensors. In the future, doctors may be able to bioprint skin cells to help heal burn wounds and print out replacement organs.

The global market in additive manufacturing hit $7.3 billion in 2017, growing at a compound annual growth rate of 21%, according to SME. Of that, 11% was in medical and dental technologies. MarketsandMarkets expects the still-emerging 3D printed medical device market to reach $1.88 billion by 2022. A number of medical device companies are betting on 3D printing to improve manufacturing efficiencies and product quality — among them, Stryker, Medtronic and Smith & Nephew. Sensors powerhouse TE Connectivity's medical products group is also invested in the space.

3D printers can cost anywhere from around $5,000 for a fairly basic unit to $50,000 for a printer with good functionality and structural integrity. For printing metals, costs can be in the $1 million to $3 million range. For that reason, many companies outsource their 3D printing jobs to businesses with expertise — either as a cost-effective business strategy or to gain knowledge of 3D printing before making that investment.

Healthcare is an exception.

"In medical, you are seeing people do more of that investment internally … because they are 100% convinced, and rightly so, that it will be a core part of their business in five to 10 years," Michael Harmon, global leader of ISG's engineering services practice, told MedTech Dive.

Potential revenue stream?

Rady Children's Hospital in San Diego is among a growing number of hospitals investing in 3D printing. After dabbling in the technology in cardiac, orthopaedics and radiology, the hospital is developing a 3D printing hub to serve all its departments.

"The orthopedics department, about six months ago, published a paper showing significant reduction in OR times for patients who had their surgery planned with a 3D model," Justin Ryan, research scientist and head of Rady's 3D printing lab, told MedTech Dive. "It was a low sample size, but there's still very strong evidence toward the effectiveness of 3D printing.

The new lab, parts of which are under construction, consists of six dedicated rooms. In addition to 3D printing, there will be virtual reality technology and space for types of manufacturing technologies, including casting technologies.

Rady views the lab as a potential revenue stream that will help build return on investment.

There is also a "makerspace" initiative — a sort of innovation pop-up space — where allied health professional and clinicians can fabricate medical devices, providing opportunities for intellectual property development.

Rady's focus in 3D printing includes models for diagnosis and presurgical planning, as well as device development and prototyping services. The hospital is specifically focused on devices not implanted in patients, such as bone fixators or ergonomic devices to help nurses prevent fatigue injuries, Ryan said. There will be some jobs, too, that require unique capabilities the hospital either can't afford or doesn't feel are within its scope to purchase, such as flexible or transparent technologies, Ryan noted. Those will continue to be outsourced.

Manufacturing efficiencies

In addition to hospitals, a growing number of medical device companies see 3D printing as key to long-term growth. Harmon told of a dental equipment maker that cleared off 250,000-square-feet of manufacturing space and installed a 3D printer. "They plan to fill that space over the next five years with nothing but 3D printers and take all of their product line in that direction," he said.

At Medtronic, 3D printing is being applied in research, technology development, marketing and education. "With 3D technology, we can rapidly create prototype devices, tooling and anatomy-based models for testing and training," Mark Bucheger, engineering director in Medtronic's cardiac rhythm and heart failure business, shared via email. "Our engineers and scientists create 3D printing concepts in hours and days as opposed to the weeks and months which were necessary for traditional methods."

The technology also allows for design and creation of complex designs and anatomical models that would be challenging and impractical to produce using traditional methods, he added.

Bucheger called Medtronic's investment in 3D technology "significant" and said it encompasses not just 3D printing equipment, but the resources and applications that benefit from the technology.

Regulatory challenges

With more medical device companies embracing 3D printing, FDA developed a technical framework to advise manufacturers planning to bring 3D printed products to market. The guidance, issued last December, covers FDA's thinking on 3D printing, referred to as additive manufacturing — from device design, testing of products for function and durability, quality systems requirements and what to include in premarket submissions.

In announcing the guidance, Gottlieb stressed it is only "FDA's initial thoughts on an emerging technology," adding that recommendations will evolve with the technology. Of particular concern is the application of laws and regulations to nontraditional manufacturers like hospitals and academic centers that are creating 3D printed devices for specific patients, he said.

"It's kind of the wild west, a little bit, in terms of every hospital doing 3D printing was kind of doing it as their own flavor," Ryan acknowledged.

That's beginning to change with efforts on standardization. In 2016, the Radiological Society of North America established a 3D printing group to address such issues, such as what are appropriate use cases and how should different types of 3D reconstruction be performed.

But FDA will have its eye on hospitals, too, to ensure hospital-made 3D printed products intended for use inside the body are safe and effective.

The agency also plans to review the regulatory issues related to bioprinting of biological, cellular and tissue-based products to determine if additional guidance is needed beyond the technical framework, according to Gottlieb.

Barriers to use

Despite rapid advances in 3D printing, challenges remain to widespread adoption in the healthcare sphere. Lack of reimbursement can be a major barrier for hospitals thinking about establishing a 3D printing lab. While an FDA-cleared 3D printed joint implant or bone fixator may be reimbursed, 3D models of a patient's anatomy and professional fees often are not.

"We are closer to achieving technical reimbursement at this time," Ryan said. "The professional fees associated with a radiologist or radiology technologist actually performing the work might be a little more challenging.

The RSNA's 3D printing group is leading efforts with CMS and the American Medical Association to obtain broader reimbursement. Meanwhile, physicians and researchers are working to compile clinical evidence of ways 3D printing improves patient outcomes.

Environmental concerns are also an issue, particularly when metals are used. While plastics normally come in a spool of plastic wire, metals start with a powder base that can be harmful if inhaled. This leads to safety concerns that hospitals purchasing 3D printing equipment may not have anticipated, such as proper storage and procedures required to fill the machines with powdered metals, Harmon said.

Device companies investing in 3D printing are more likely to have technical staff to oversee these concerns, but both hospitals and manufacturers need to comply with EPA regulations affecting use of powdered metals in 3D printing.

Other challenges include education and craftsmanship. Currently, there are no 3D printing in medicine programs at U.S. colleges and universities. "It's very much a mentor/mentee relationship," with people learning on their own or reaching out to colleagues with 3D printing experience, Ryan explained.

But it also leads to concerns about craftsmanship. For example, there is a deformation that has to be compensated for when melted metals cool. Software that comes with the printer can mitigate some of that, but there is still trial and error to 3D printing. Harmon said hospitals going down this path should seek out people with specific experience to avoid paying for that trial and error.

"A lot of companies have spent $1 million or $2 million on a piece of equipment, and not only are they not able to realize that cost back out of it, get that return on investment, in some cases they're not even that able to run the machine because they don't have the true technical capabilities internally to do that," Harmon said.

Finally, there is the technology itself. There have not been any revolutionary changes in the mechanics of 3D printing in recent years, such as faster product turnout. But there is some proliferation of lower-cost printers such as FormLabs' Form 2 in hospitals, noted Ryan.

HP has made full-color 3D printing a priority. The company also recently introduced the Metal jet printer, an industrial-scale 3D printer that could impact the medical devices sector.

A big unknown is how Hewlett-Packard's new 580 color printer will impact the hospital space. It's similar to the already launched 4200, but smaller, according to Ryan. "We're curious to see how that develops. If the speed they present isn't significantly faster, if we're trying to do trauma cases where we have literally hours, that might not be feasible," Ryan said.